Portraits In Jazz

Polymath Humphrey Lyttelton not only played as he pleased, he wrote as he pleased in many excellent books on music, once appealingly disparaging sound engineers he suffered on tour as 'Marconis'. The reason? They couldn't stop fiddling with the controls, so destroying the natural balance of his live band and adding electronic distortion.

But all too often – especially in 'autobiographies' largely ghosted by a hired hack – books about musicians are as sycophantic as a pop fanzine. So here I have had a go at naming some of the best books about music, with the filter that they offer useful insights into audio. Because I found so many good reads, I've narrowed the field for this feature to jazz.

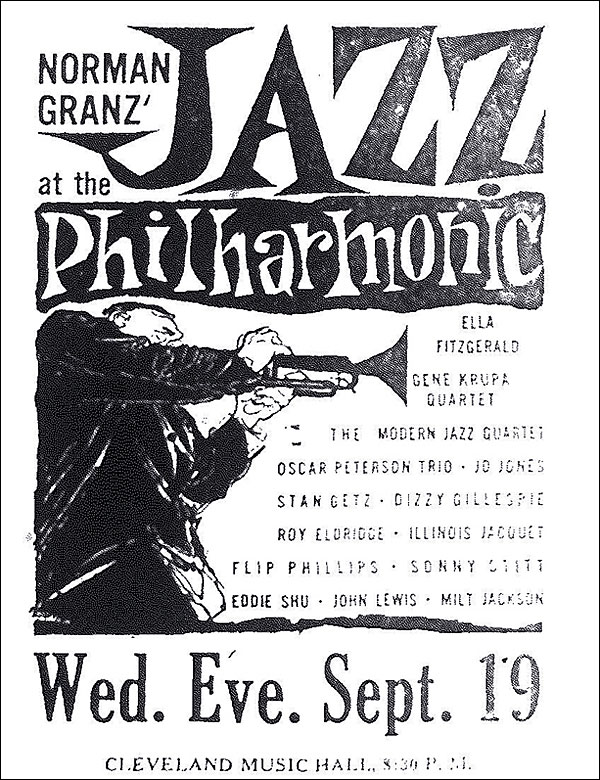

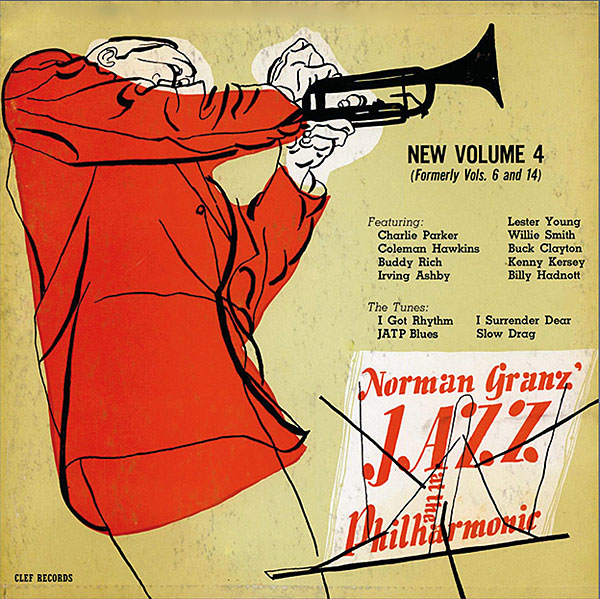

It's not hard to see why many music biographies have been bland. Take jazz entrepreneur Norman Granz, for example. He produced countless studio recordings – including the seminal set of Great American Songbooks sung by Ella Fitzgerald – and recorded his live concert promotions with simple mic set-ups, notably the Jazz at the Philharmonic extravaganzas. He also exploited the then-new LP vinyl format to let musicians stretch out past the three-minute barrier.

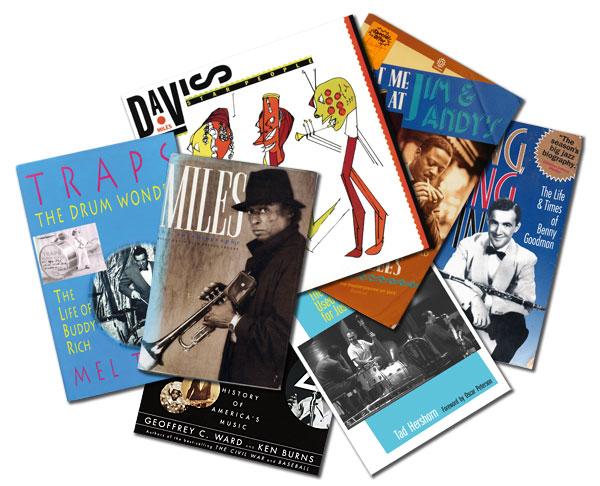

Granz didn't want his life documented, often 'professing a hostility to history' as author Tad Hershorn put it after having to wait until after Granz died to piece together his excellent biography The Man Who Used Jazz For Justice.

He tells how Granz 'ignored Ken Burns's TV documentary Jazz, airing in January 2001, despite repeated interview requests [saying] "I will be dead by the time the programme is broadcast, and I don't care what people think of me after that"'. Hershorn then recounts what happened when Stuart Nicholson wrote his biography of Ella Fitzgerald, who was managed by Granz.

'Nicholson found himself at the receiving end of a threatened lawsuit by Granz… Granz knew British libel laws well enough to know that he would have a far easier time making a case there.

'Granz itemised his complaints to Nicholson in what must have been an excruciating phone call lasting some four hours. Nicholson gave in: a comparison of the 1993 edition with the American edition reveals passages deleted or revised.'

Fever Pitch

The edition of the Ella Fitzgerald book which I bought, dated 1996, is similarly sanitised. But it is still a wonderful book I'd recommend. For instance, Nicholson sums up why Ella sounds like Ella by explaining how she was gifted with relative pitch, which is 'different from perfect pitch – a term for the ability, on hearing a note, to identify it by name in that the possessor of relative pitch knows the precise relationship of every other note to the note sounded and can hit them perfectly in tune'.

Here Nicholson quotes the equally fine singer Mel Tormé: 'I am still trying to find an Ella Fitzgerald record where she sings one single note out of tune, and I'm failing. I can find plenty of my own'.

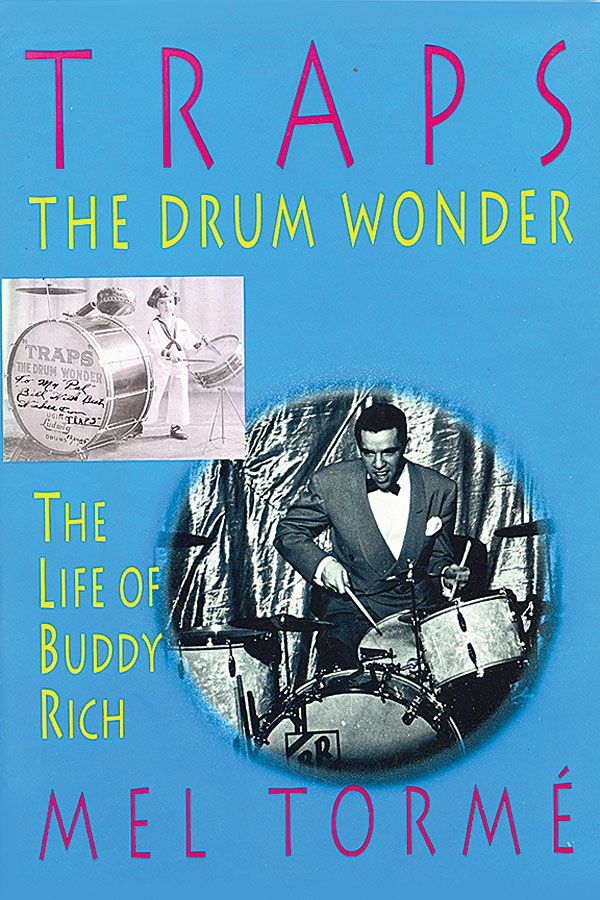

Mel Tormé, by the way, has written two fine books. There's his autobiography It Wasn't All Velvet and Traps The Drum Wonder, a biography of drummer Buddy Rich.

Nicholson also goes on to very helpfully describe the origins of Jazz at the Philharmonic recording: 'In 1944, Granz took the ambitious step of arranging a promotion at Los Angeles' Philharmonic Auditorium to raise funds to provide a defence for Mexican youths arrested in the so-called zoot-suit riots in the city. He had to borrow money to stage the show, which turned out to be a sellout, and the "Jazz at the Philharmonic" concept was born.

'Significantly, he had reached an agreement with the Armed Forces Radio Service to record the first concert to beam to American GIs. After the concert they presented him with 16in acetates of the proceedings, which, after some difficulty, he managed to get released by Moe Asch on his Asch label. At the time, the concept of live recordings for commercial distribution was resisted by recording company executives who thought crowd noises intrusive.... Norman Granz had seen a hole in the marketplace and exploited it. By 1952 he was grossing a million dollars a year.'

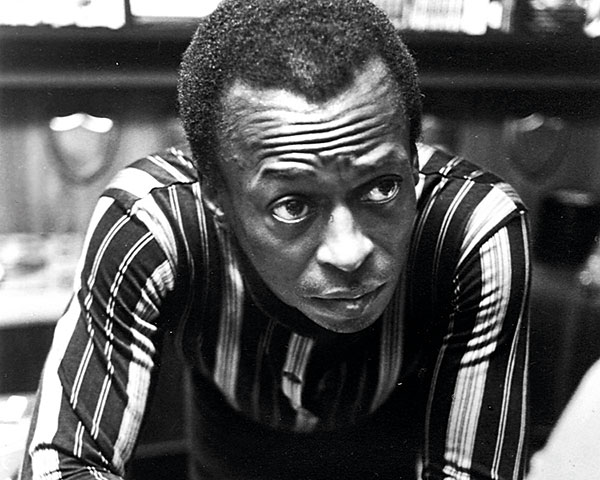

Musicians who make tender music are often the least tender of people – as you will learn if you read the books written on music's very own Prince of Darkness, Miles Davis.

Basement Tapes

In Miles, the official autobiography Davis wrote with Quincy Troupe, Miles admits that 'a lot of what went on in the studio I just forgot'.