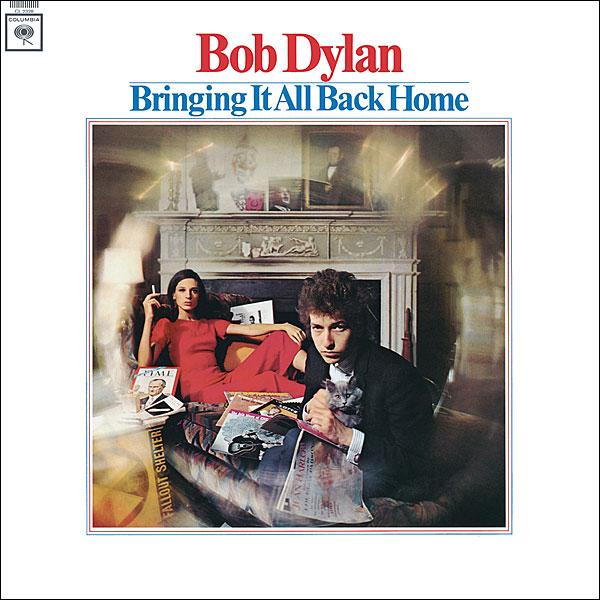

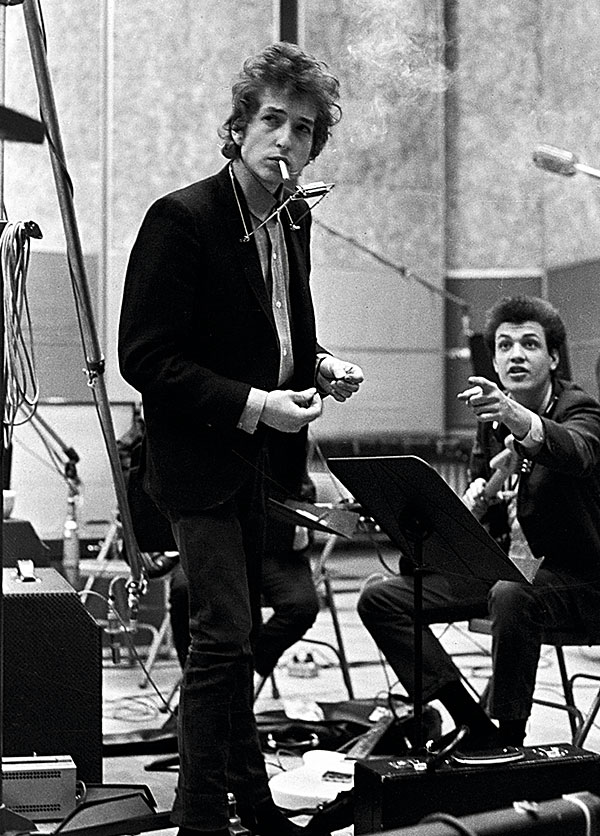

Under the covers... Bringing It All Back Home

The artist formerly known as Robert Zimmerman broke new ground in all kinds of ways. But one field where his pioneering role isn't often acknowledged is sleeve art. By the early 1970s, it was standard practice for fans to pore over LP covers pondering the significance of the imagery presented to them. But in 1965 the profundity of most popular music album artwork didn't extend much further than a shot of the band looking mean and moody, or happy and playful depending on the image they'd chosen to portray.

By the start of that year, though, Bob Dylan was already preparing to challenge the limits and expectations applied to popular music artists. Not only was he gearing up to break out of the insular, puritanical folk scene by going electric on his fifth album, Bringing It All Back Home, but he was also ready to further toy with public preconceptions with an album whose artwork (and its surreal sleeve notes) hinted at a previously untapped world of influences and reference points.

The whole package would reflect an artist ready to represent something culturally much more formidable than the 'song and dance man' he sardonically referred to in his pithy press interviews.

New York State Of Mind

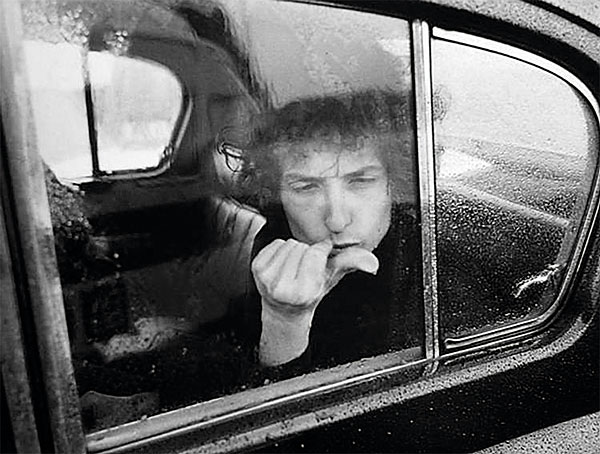

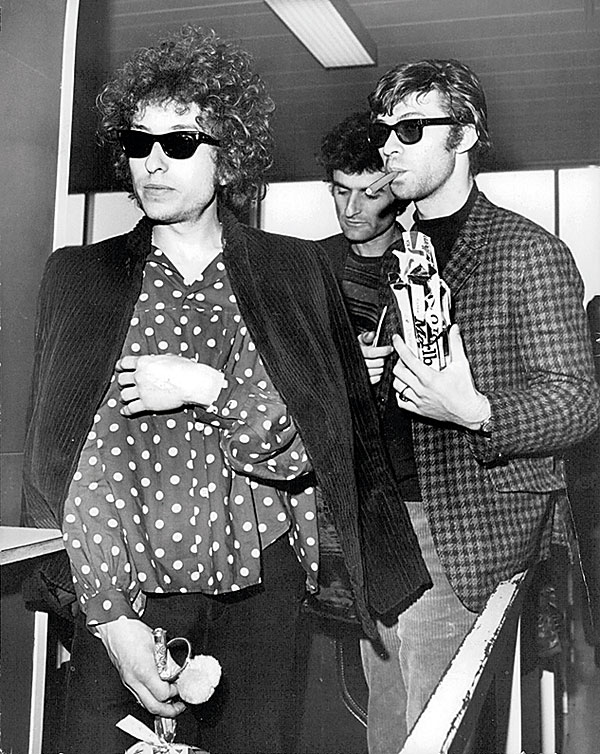

By the time Bob Dylan and freelance photographer Daniel Kramer travelled to the home of Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, in upstate New York in early 1965, Kramer had struck up a burgeoning friendship with the inscrutable Minnesotan. Kramer had first fallen under Dylan's spell a year previously after seeing him on TV and, being ambitious, had badgered the young folkie's manager for a chance to shoot a subject who, while hardly conventionally photogenic, exuded an undeniably magnetic charisma.

He finally got his way that summer at Grossman's home and bonded with the 23-year-old over a shared fascination with Salvador Dali (Kramer had assisted a photographer who had shot the mercurial Spanish artist several times), while photographing him in anything but portrait pose. ('[Dylan] said, "You can do anything you want, you can shoot anything you want the whole day, whatever you want – as long as I don't have to sit still in the chair"', Kramer later recalled.)

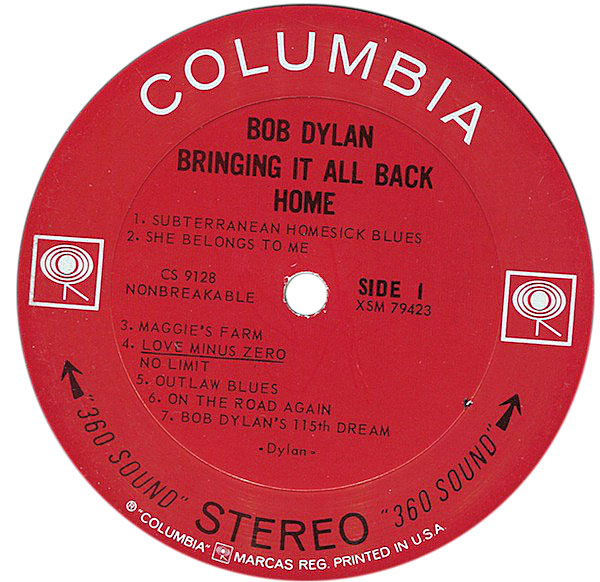

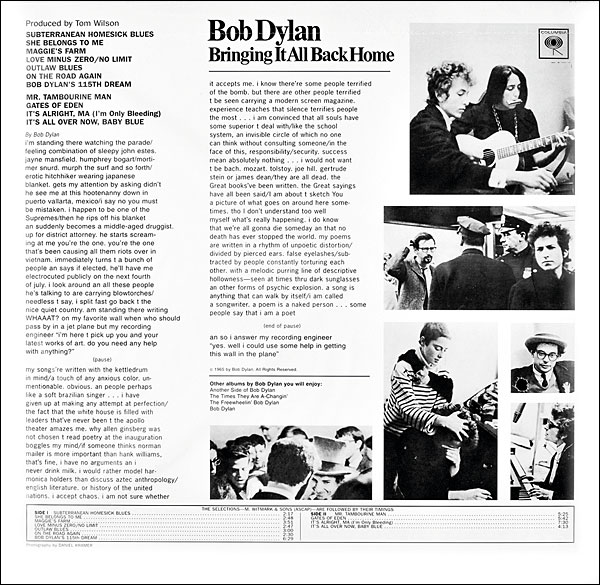

Dylan and Grossman liked the shots and the photographer would hang out at subsequent shows and also be present at sessions for the next album at Columbia Studios in New York, where guitars were plugged in and a significant artistic Rubicon was crossed. The album would be titled Bringing It All Back Home, and Kramer was the obvious choice to shoot the cover. Or so it seemed to Dylan and Grossman. The record label had other ideas.

'I went to the art director at Columbia Records', Kramer explained at a November 2019 exhibition. 'I said, "Bob would like me to do the album cover…" and he said, "You can't do it… Bob's a superstar. I need a superstar photographer to do it"'.

Sad-Eyed Lady

As a relative newcomer to rock photography (despite being 33), Kramer accepted this decision, but Grossman was having none of it. According to Kramer, he marched both him and Dylan into the art director's office and, well, 'It was very ugly. But when we left I was going to shoot the album cover'.

However, the label did manage to negotiate one thing: they insisted there had to be a girl in the shot, as there was on The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. Dylan wasn't keen on having his girlfriend Sara Lownds as the model, possibly because he was still seeing Joan Baez at the time. Instead, the model nominated for the job was Grossman's wife Sally. 'Bob wanted Sally to be in the photo because, well, look at her!' Kramer later told The Guardian.

The set-up of the shot was a more intricate matter, though. Kramer's idea for the shoot was for the main man to be at the centre of a chaotic world represented by all kinds of bric-a-brac strewn across the scene. After being shown a polaroid of the intended image, 'Bob contributed to the picture the magazines he was reading and albums he was listening to', Kramer explained, while the photographer and Grossman also added the odd contribution.