ECM Records at 50 Page 2

Key Recording

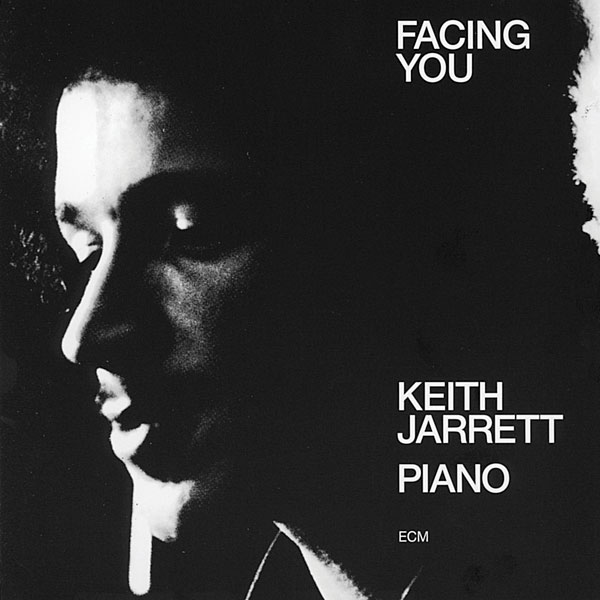

This was the first of many, many ECM albums to be recorded in Oslo with Jon Erik Kongshaug as recording engineer. 'After we recorded it we knew we had something special,' says Eicher. He sent the record to Keith Jarrett, who was impressed, and in November 1971, Eicher brought Jarrett to the same Oslo studio to record Facing You [ECM 1017], his first solo piano recording. Then, just two years later, the label having organised Jarrett's successful 18-date European tour, ECM offered the triple-LP Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne [ECM 1035-7].

Jarrett's next solo tour didn't seem to be going so well when he arrived in Cologne in February 1975, exhausted from travel and suffering severe back pain, to find that the Opera House had got out a battered rehearsal piano instead of the one requested for his performance there. But Jarrett turned disaster into triumph, and The Köln Concert [ECM 1064/5] became the label's biggest hit, eventually selling more than 3.5 million copies.

Mail Order Music

While all this was going on, ECM was also responsible for the JAPO label, active from 1970 to 1985. Back in 1967, Manfred Scheffner had started a mail-order service for jazz records based in the Elektro-Egger appliance store in München-Pasing, and from this developed the Jazz By Post or JAPO label. Scheffner was also to become well known as the editor of the Bielefelder jazz catalogue.

Mal Waldron, this time accompanied by local musicians, featured again on JAPO's first LP, The Call [JAPO 60001]. There were also albums from Abdullah Ibrahim, Enrico Rava and Elton Dean, as well as several cross-genre artists. Land Of Stone [JAPO 60018] featured the Celtic jazz of Talisker, led by drummer Ken Hyder, who incidentally was also for many years a Hi-Fi News jazz reviewer.

Of the 41 JAPO titles issued, some involved Eicher but many were produced by the late Thomas Stöwsand, a cellist and flautist who'd played with Just Music. He had joined ECM in 1970 to look after distribution, and it was he who championed the strategy of booking concert tours to promote sales. From 1983, though, he ran his own booking agency.

By this time ECM had ventured into the contemporary written music of Steve Reich and Meredith Monk, and in 1980 Keith Jarrett had recorded Gurdjieff's Sacred Hymns [ECM 1174]. But in 1984 came the New Series, loosely thought of as ECM's classical label. It began with the music of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, which Eicher had discovered by a happy accident. Here's how he tells the story:

'I believe it was in 1980, when I drove from Stuttgart to Zurich, and found on the radio some music that I'd never heard before. So I left the autobahn and listened from on top of a hill where there was better reception. The music was angelic, so incredible that I continued listening for the next half-an-hour. But I didn't know what it was and it took me quite a while to find out that this was music by Arvo Pärt.

'We later met in Vienna and discussed the possibility of recording together, and thought about different musicians.' The tape Eicher had heard in the radio broadcast was a recording of Gidon Kremer performing with Tatiana Grindenko in Tallinn in 1977. But Eicher wanted to record something new. 'We didn't have a recording of Fratres,' he continues, 'so I suggested to Arvo Pärt, who also knew Keith Jarrett, that we make this recording with Keith and Gidon Kremer. I had in mind Keith because of his recording with Gurdjieff that we had done before.

'And we made the recording in one night, and it was actually a very, very rewarding and vivid and electrifying recording, that could never be repeated afterwards. And they never played together again.'

New Series

'This was the first step,' continues Eicher. 'And then the next recording was with Dennis Russell Davies, which was the Cantus In Memoriam Benjamin Britten. Then we recorded, with the cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic, another version of Fratres in Berlin. And we made the montage with Tabula Rasa, which existed as a live recording from the Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Köln. We then made edits and some sound retouches and then brought it together. It was actually quite a spectacular soundscape that we arrived at, and Arvo was very pleased. And we found a good dramaturgic line from beginning with Fratres to Cantos, then Fratres again and we ended with Tabula Rasa.'

So for the final release, which of course was a huge success, Eicher had cleverly matched up a live 1977 recording with his own new studio recordings.

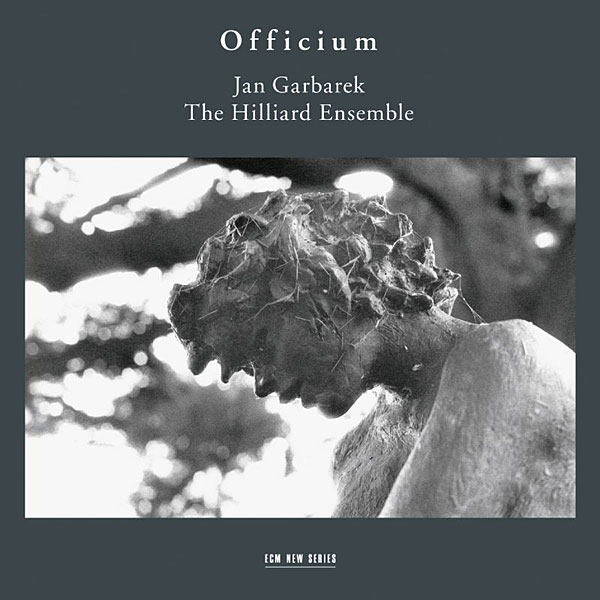

In 1994, the New Series offered a quite revolutionary combination of written and improvised music, when Eicher added Jan Garbarek's saxophone to the early-music voices of The Hillard Ensemble on Officium [ECM 1525]. There were no written parts for Garbarek, who just responded nimbly to what he heard from the singers.

Breaking Barriers

With Officium, ECM showed again how it could expand its audience by intelligently breaking the barriers between genres. But the label also had its detractors, often with sentiments that were summed up neatly by Richard Williams, writing in The Guardian in 2010: 'To its many admirers, ECM stands for a certain meditative introspective approach to playing and listening. Its albums... are recorded and packaged with a deliberate refinement, once upsetting to those who concluded that Eicher had somehow squeezed the vitality from the jazz he professed to love, contaminating it by an association with his north European sensibility'. But, Williams goes on, 'That argument seems to have been won'.

Asked by Irish Times writer Cormac Larkin about 'the ECM sound', Eicher commented 'If people think that we ask musicians to record for us because we want to sculpt their sound in a certain kind of way, that's nonsense. We chose musicians for their music'.

It wasn't until November 2017, by which time the record industry's digital income had finally overtaken its income from physical media, that ECM began to release its catalogue for streaming via Apple Music, Amazon, Spotify, Deezer, Tidal and Qobuz. A press release explained:

'Although ECM's preferred media remain the CD and LP, the first priority is that the music should be heard. The physical catalogue and the original authorship are the crucial references for us: the complete ECM album with its artistic signature, best possible sound quality, sequence and dramaturgy intact, telling its story from the beginning to end.'

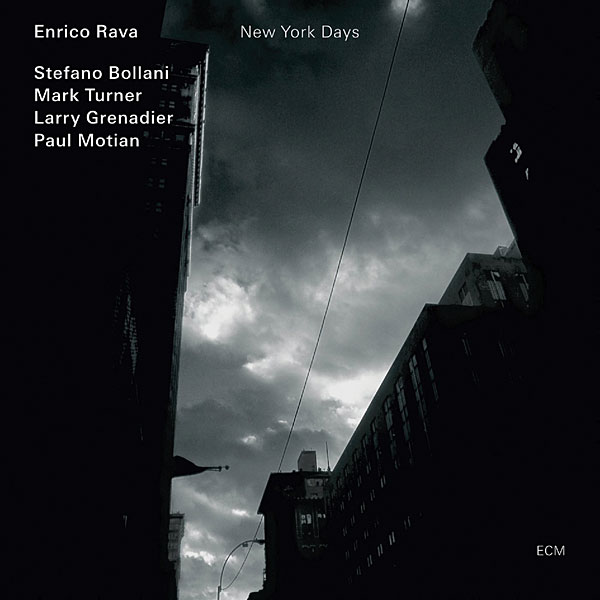

Like other companies, ECM had stopped issuing new titles as LPs in 1992, although some back-catalogue titles remained available (on standard 140g vinyl) for a while. So in 2009 Keith Jarrett's Yesterdays [ECM 2060] and Enrico Rava's New York Days [ECM 2064] became the label's first new releases on vinyl in 17 years, both double-LPs on 180g vinyl. Yesterdays, though previously unreleased, had been recorded live in Tokyo back in 2001.

Special Issues

Writing in 2010, Richard Williams tagged Manfred Eicher as a man who had survived the 'virtual disintegration' of the record industry around him. A decade further on and his label has celebrated its 50th anniversary with a year-long cavalcade of special issues and events, including a re-release of that first, seminal LP, Free At Last.

No-one knows if physical music media will still be around in another 50 years. But ECM will.