Day the Music Died Page 2

Tony Faulkner of independent Green Room Productions says that the music industry has changed radically over recent years, away from the cartels of all-powerful music majors – much as Hollywood has moved away from the old all-powerful studio system.

Says Faulkner: 'The average record company Joe at any level of A&R management will have assumed they are automatically covered because they have some kind of physical media in a library somewhere, the originating studio will have retained something they assume, and there will be multiple copies with download systems and streaming systems coordinators.

'Increasingly, record companies do not own the material they release, they license it in from third parties: artists, agents and managers. Consequently, the record companies might consider that they do not have any life-threatening requirement to preserve the content safely and securely beyond the questions of internal convenience, due diligence and duty of care – principally making sure no new-release content leaks out before it was supposed to. So the responsibility in this circumstance of third-party ownership of content remains with the owner of the content licensed onward to the record company.

'I cannot remember the last time we invoiced a major or even middle-size record company for a recording project – we nearly always invoice artists direct, their managements, their production companies or a moneybags sponsor.'

So if it's no longer safe to assume that record companies are securely storing music or ensuring someone else is securely storing it, then who is?

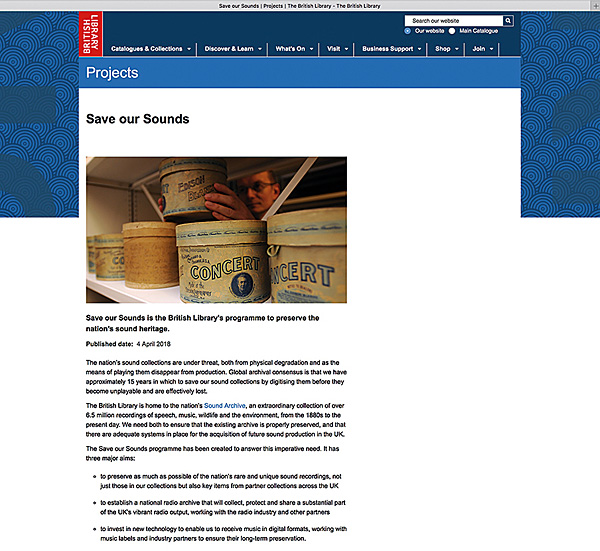

There has been a 'legal deposit' system in the UK since 1662, whereby a copy of everything published in the UK must be given to the BL for safe keeping. Since 2013 this includes digital publication. But there is no such requirement for music. Some of the record companies give some of their recordings to the BL, on a voluntary ad hoc basis, but most of what the BL stores is 'non-published' material – recordings which you cannot buy.

This means that the BL has to digitally archive from a wider variety of media sources – discs, tapes, cassettes, cylinders, you name it – it has had to access it. The BL initially copied everything to Sony Betamax VCRs, with PCM-F1 analogue-to-digital converters, set at 44.1kHz/16-bit linear. Even before Betamax died (Sony stopped making Betamax hardware in 2002), the BL had been buying up Betamax decks to cannibalise for spares. The BL also had to buy up VHS machines because as Betamax died people tried using VHS for digital recording.

Survival Skills

'It's not just the machines that are disappearing, it's the expertise,' warns Adam Tovell, 'it's the skills. There are no university courses that teach this kind of legacy expertise.'

After a flirtation with optical discs (gold CD-Rs and DVD-Rs) the BL is now storing everything on hard disk, using the now standard format IASA TC04 laid down by the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives. For the digitisation of analogue audio recordings, IASA recommends a minimum digital resolution of 48kHz/24-bits, using linear pulse code modulation (LPCM) WAV file encoding, and no compression. The trend is now towards 96kHz/24-bit, which is what the British Library Sound Archive uses.

'Some people say 192kHz/24-bit would be better,' says Tovell, 'but the amount of storage capacity then becomes a real issue. Actually, what matters more is making sure all the equipment is correctly aligned, so we get off what was put on. When we archive original digital recordings, like F1 tapes, we use the same bit rate as the original, without processing. We copy, warts and all.'

Save Our Sounds

The Sound Archive currently has a team of around 20 technicians, each working with four transfer machines.

'We give priority to the unpublished material,' says Tovell. 'We are currently storing around a terabyte a month, of music and speech, wildlife and radio drama recordings. So far we have archived several hundreds of terabytes of data on hard disks, which is around 8% of the BL's collection. So we are only scratching the surface.

'But it's not all doom and gloom. The Heritage Lottery is funding storage of 110,000 physical items and 50,000 from other institutions. We are looking for more funding for our Save Our Sounds drive.'

The SOS message is simple: 'Global archival consensus is that we have approximately 15 years in which to save our sound collections by digitising them before they become unplayable and are effectively lost.' (See here.)

Hard Life

John Watkinson, highly respected author of many text books on all things digital, throws a typically provocative thought into the mix:

'I have to say it amuses me that people transfer data from CDs to a single hard drive, thereby going from a medium having no wear mechanism and a life measured in decades to a medium that is ephemeral in comparison.'

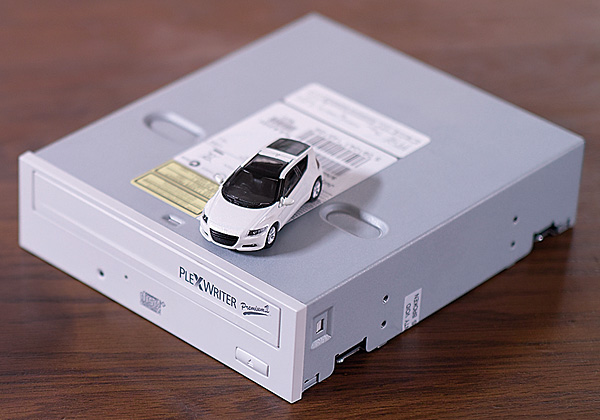

Adam Tovell explains the BL's thinking on this: 'We stopped using optical media because hard disks were becoming more affordable and the data is instantly accessible, so easier to take care of. Also the quality of CD drives is not as good now as it was. CD drives from the 1990s were much more accurate at reporting errors. If the drive makes 'pass' or 'fail' mistakes when checking C1/C2 errors it goes into interpolation, which is guesswork. We have stockpiled good old drives, especially CD writers such as the Plextor Premium 2.'

The BL uses conventional computer hard disks (currently with maximum capacity of 8TB) but in RAID arrays (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) where the stored data is 'striped' or spread and duplicated across several discs, so that if one disc fails the data can be recovered from the others.

The BL uses RAID 6, or double-parity RAID, with two parity stripes on each disk which allows for two disk failures within the RAID set before any data is lost. The same RAID 6 data is stored at four different geographical locations: at the BL in Kings Cross, Wales, Yorkshire and Edinburgh.

'That way if London goes, we still have the file safe somewhere else,' Tovell says pragmatically.

Contrary to perceived wisdom the BL has not yet seen hard evidence that there is increased risk of bit-flipping due to the size of a drive. Says Tovell: 'The un-correctable read error rate (as quoted by the manufacturers of the disks) remains the same at approximately one unrecoverable error per 1x1015 reads.' He continues: 'We now want to acquire music files, and the metadata that comes with them, from the “aggregators” who are supplying content to the music streaming services,' he says. 'We would want it with a minimum of 44.1kHz/16-bit WAV quality.'

Talking with the BL left me confident that the solutions now exist to preserve digitised audio securely and indefinitely – but nowhere near confident that the music industry is exploiting the available solutions. It has also encouraged me to start asking questions about checksums when next a hi-fi company is promoting a home server. Says John Watkinson: 'Most media don't display the error rate and most consumers wouldn't know what it means.'

Reality Bites

And how many music-lovers with home server systems are sensibly making back-ups but not so sensibly storing them all under the same roof where they are all at the same risk from fire, flood or burglary?

Norway has recently introduced a compulsory legal deposit scheme for music and broadcasts. This is more workable in a small country with much more limited music production than the UK. But with the record industry changing so radically, maybe it's time for the UK to introduce a similar scheme?

If so, I don't envy the Brit politician who would then have to explain the choice between funding more hospitals and paying to store music securely because the record industry isn't doing the job.