Day the Music Died

The recent movie Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, nearly never got made. Which would have been a pity because it tells the intriguing story of how the glamorous film actress (legal name Hedy Kiesler Markey) and her husband, composer George Antheil, filed for a US patent in 1941 on the frequency-hopping, spread-spectrum communication technology that underpins modern wireless networking, including Bluetooth and Wi-Fi.

Although a few patent historians have known about the Lamarr/Antheil filing for some time, the back story to their invention has always been a mystery. But Bombshell Director Alexandra Dean unearthed a stash of audio cassette tapes of a gold dust interview that Lamarr gave to a US journalist late in her life.

Sticky In Storage

When Dean tried to play the first cassette it jammed in her player. The tape inside had 'gone sticky' and was shedding magnetic coating as goo. Luckily an audio engineer working on the movie knew how in the late 1980s the professional recording industry had found that even carefully stored master tapes were becoming unplayable. He also knew the trick of baking sticky tapes for around eight hours in a low heat oven to make them playable for just long enough to make a digital copy.

So the Bombshell crew stopped trying to play the Lamarr tapes, and thereby destroying them, until after they had been baked. Which prompts a sobering train of thought for all of us who have audio stashed in cupboards under the stairs, up in the attic or down in the cellar. How many of us also have working hardware to play our old recordings? Have tapes gone sticky? Have discs grown fungus or warped into saucers? Has the supposedly sealed coating on our CDs let damp in the air leak through and corrode away the reflective layer?

I'm fireproof, I hear you say, because I have transferred all my music to computer hard disks. Don't be so sure. Hard drives fail. So does solid-state memory. And even if a drive still works, how do we know whether the data stored on it is still error-free, or that the error rate is still low enough to be correctable?

And that's just us. If the tape manufacturers and the record companies got it so horribly wrong with analogue master tapes that went sticky in storage, where's the guarantee that they will get it right with long-term storage on hard drives? How seriously are they taking the computer industry's early warnings that even carefully stored hard drives can suffer spontaneous 'bit rot' or 'fixity' problems?

Hard disks are now so physically small and store such huge amounts of data that the magnetic domains are insanely tiny. This can make them vulnerable to spontaneous polarity switching caused by chemical or mechanical changes.

When I first wrote about bit rot in these pages [HFN Jan '18] I asked the over-arching body for the record industry, the IFPI, what it thought about the issue. Not a lot, it turned out. In fact the only comment I ever squeezed out of the IFPI was largely waffle from an anonymous spokesperson.

'We recognise the significance of preserving the vast creative output of the music industry, but we also recognise that the expertise on media preservation is itself a separate area… We have not issued specific guidance on data degradation issues but know there is wide awareness and plenty of expert advice available on data backup and preservation from the consumer level, right through to specialist archival needs.'

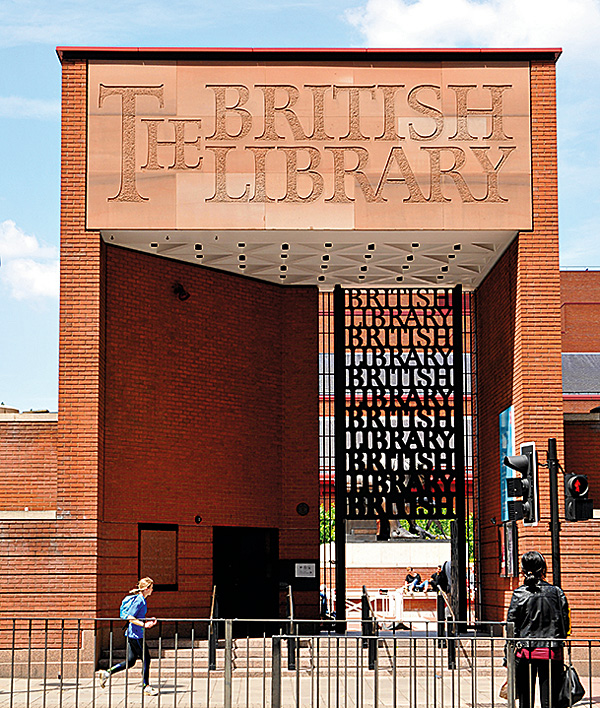

This made me wonder who was taking the issue of bit rot and fixity seriously. So I asked the British Library, which incorporates the National Sound Archive (formerly the British Institute of Recorded Sound) and holds more than six million recordings, including over a million discs and 200,000 tapes.

Endangered Digital

Says Head of Digital Preservation, Maureen Pennock: 'Bit rot can manifest on any storage device, from floppy discs to hard drives. In the early 2000s we began developing our own purpose-built digital repository for long-term storage. We work particularly closely with the Digital Preservation Coalition and the Open Preservation Foundation, two international membership organisations that we helped to establish.

'Recent work with the DPC included sponsorship of the Digital Preservation Handbook, which includes a section on fixity checking. The Handbook is a free resource available to all, members or not.' (See here.)

The DPC has now drawn up a 'Bit List' of the World's Endangered Digital Species, analogous to the lists of endangered wildlife.

'Teletext and the BBC's Ceefax are an example of digital material which is now practically extinct and cannot be accessed by any practical means,' says Executive Director of the DPC, Dr William Kilbride. 'Both our libraries and archives have good collections of printed newspapers, but for the late '70s, '80s and 1990s there's a gap relating to this genre of online news.'

I visited the British Library's headquarters in King's Cross and spoke with Head of Technical Services Adam Tovell. He leads the 20-strong team currently working on the secure storage of audio material. The key to open-ended preservation, he says, is detecting signs of corruption while there is still time to repair and replace data. This may sound obvious, but it's easier said than done.

Big Red Flag

The detection of corruption is by 'checksum', a 'digital fingerprint' which acts as a snapshot of the bit structure of the entire file. There are several kinds of checksum but the BL has standardised on SHA-256, which constructs a 256-bit file description. Even the smallest change to the file will cause the checksum to change completely, which acts as a big red flag that something somewhere in the file has altered.

The checksum warning flag does not tell us what has changed and where in the file. But this does not matter as long as several check-summed copies of the same file exist. A copy with a 'good' checksum can be used to replace the copy with a 'bad' checksum. A new checksum is then made for the new, good file. This procedure is known as 'data scrubbing'.