Building A Vintage System Page 2

Vintage turntables, once correctly overhauled, are a fine addition to a modern set-up. Linear-tracking decks with servo-controlled arms are a rarity today but were commonplace in the vintage era. Big decks such as the Sony PS-X800 and Pioneer PL-L1000 give a good demonstration of what linear tracking can do, while one has to go a long way to improve usefully on the little Technics SL-10 [HFN Apr '19] and its derivatives.

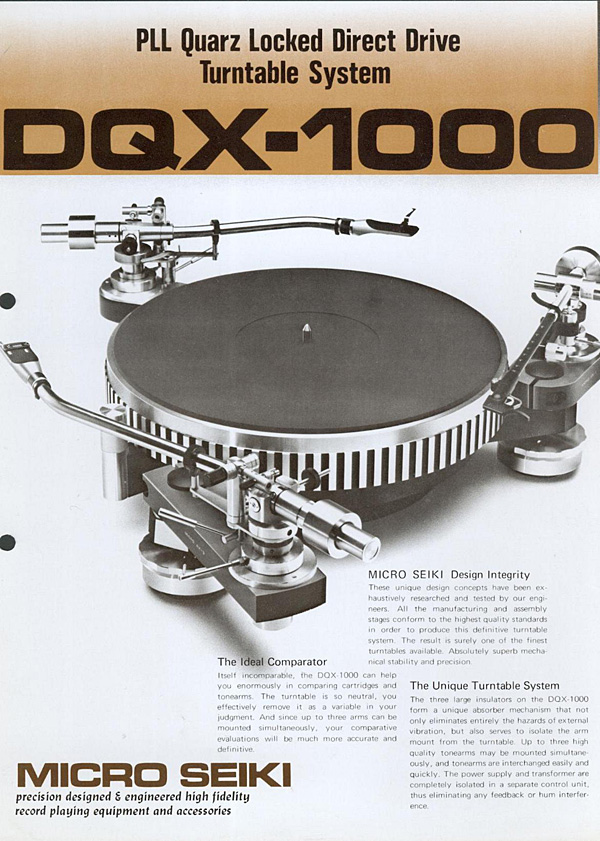

An old deck equipped with a modern arm is another popular combination. Micro Seiki's DDX or DQX-1000 is probably the ultimate choice in this respect, but there are plenty of Thorens TD160s, Technics SL-150s [HFN Oct '15] and old Rega decks out there for those who wish to experiment at a more modest level of expenditure. If available, a modern pick-up is advisable in any system where originality is not paramount. In fact, vintage cartridges are a minefield and are best avoided by all but the most committed.

Similar comments could be made about loudspeakers, and it is unusual to see vintage loudspeakers used in an otherwise modern system. There are exceptions, of course, Quad electrostatics and the various BBC-based designs have characteristics that have not been completely replicated elsewhere. So if you like their sound, the originals are the ones to go for. The same holds true for the Philips Motional Feedback series [HFN Jan '13]. Nothing like it has really been made since, so again, if you appreciate the way these speakers sound, the old ones are your only choice.

Technical Issues

Combining sources and amps from different parts of the globe is complicated by the fact that two basic standards existed throughout the vintage era. In the '60s and '70s, the bulk of Japanese and American equipment used 'line level' signals, whereas the DIN standard was common across Europe. British makes used either, sometimes employing the connectors from one standard with the signal levels of the other. The Nytech CTA-252XD receiver [HFN Jun '17] is an example.

The DIN standard had its own connectors, ranging from three to eight pins but most commonly seen with five. This allows for stereo recording and playback through one simple cable, and on the whole the manufacturers got the pinning right so everything worked smoothly. Equipment that works at line level typically uses RCA connectors which, of course, are still familiar today.

The output level from a DIN-standard source is much the same as that from a line level one, so apart from having to make or buy the adapters needed there are normally no difficulties here. The recording output from an amplifier is quite different though. Line level recording outputs are the same as the source inputs, but under the DIN standard they are much lower, similar to the signal obtained directly from a microphone.

Connecting a DIN-standard recorder to a line level amplifier may result in overloaded recordings at any setting of the level control, while connecting a line level recorder to a DIN amplifier may give results that are not only very quiet but noisy.

Because the DIN standard specifically does not allow for 'off tape' monitoring from a three-head recorder, various non-standard arrangements exist to provide this function – even in those models made by otherwise strict adherents to the DIN system (eg, Philips). Two separate sockets are often used, the input one sometimes having line level sensitivity. Being able to make one's own cables helps a lot when dealing with set-ups such as these.

Sense On Sensitivity

DIN connections for turntables use the outer shell of the plug for the 'chassis ground' and pin two (the centre one in the arc of five) for the 'signal ground'. This avoids the need for a trailing earth wire, but it also means that simple adapters (eg, those intended for tape decks and tuners, etc) can't be used.

The easiest way to judge input sensitivity is to be aware of the position of the volume control when playing a source at a moderate volume. If the sound is clipped and distorted or it's difficult to set the control at low listening levels then the amplifier's sensitivity is probably too high for the source in use. This is often a problem when using a CD player with equipment made well before the CD era. Attenuators are available to solve this problem, and these connect between the source component and the amplifier, reducing the signal to a more manageable level.

Loudspeaker matching is not helped by the vague nature of the specifications given by manufacturers of the vintage period. However, over-driving a speaker will cause the voice coils to burn and distort their formers, jamming the centre of the cone in the magnet assembly or causing it to rub. This is rare, however. One usually encounters open-circuit tweeters that have been overloaded by the distortion produced by a struggling amp.

As for impedance, this is of little consequence unless you intend to use the full power of the amplifier. It was a critical factor with low-powered valve amplifiers since it was desirable to achieve the highest efficiency possible. An amplifier built to drive two sets of loudspeakers will normally drive one pair of almost any impedance with ease. Again, at listening levels associated with 'high fidelity' one is unlikely to encounter any problems associated with loudspeaker impedance matching.

On The Contrary

Sensitivity is another issue that comes into play when matching loudspeakers. Contrary to what one would expect, larger loudspeakers tend to require less power for a given perceived sound intensity than do small ones, so a bigger amplifier is often required to drive small speakers. Sensitivities of 90dB/W/1m and above can be considered 'high' for matching purposes, and you won't need a very big amplifier to make a lot of noise with a speaker having such a rating. On the other hand, anything in the mid-to-low 80s is considered 'low', meaning a large amp may be required to achieve realistic listening levels (assuming that the speakers can take it!).