Recording the Classics

Before my local bank branch closed, someone in head office came up with a cunning plan. Shut half the counters and pipe in classical music to soothe the nerves of customers seething at the longer wait for service. Played just loud enough to be recognisable, but too whispery to be enjoyable – like the tizzy spill from someone else's headphones – the noise just simply annoyed.

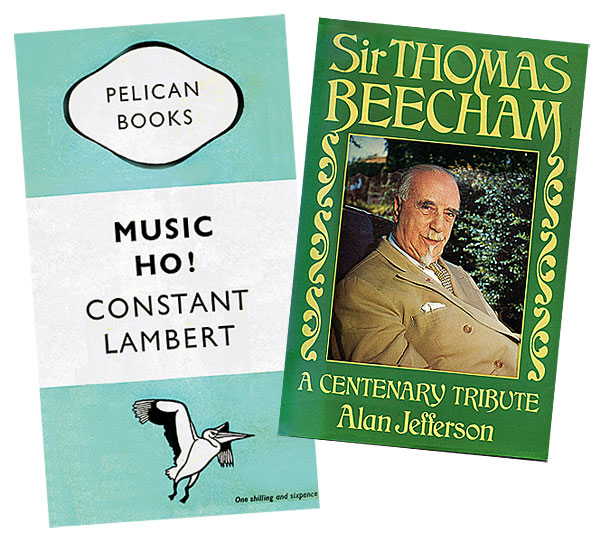

Same old same old. In his 1934 book called Music Ho!, Constant Lambert, then Music Director of The Royal Ballet, railed against 'the appalling popularity' of music. 'Music of a sort is now everywhere and at every time... We board buses to the strains of Beethoven and drink beer to the accompaniment of Bach.'

Tonal Debauch

Coining the phrase 'canned music', Lambert reckoned 1934 was 'an age of tonal debauch'.

'I have heard a woman of some intelligence and musical training actually state that she preferred the magic tone of the oboe over the wireless to the actual sound of it in the concert hall; and I have heard a painter, who prides himself on his modernity, state that the two-dimensional effect of broadcast music was to be preferred because the sound instead of escaping round the hall came straight at you and had "a frame"'.

Sir Thomas Beecham, with the London Philharmonic, collaborated with Alan Blumlein of EMI to make a stereo test recording of Mozart's 'Jupiter' Symphony at Abbey Road in January 1934. Then, in 1936, Beecham conducted the LPO for a concert in the IG Farben/BASF concert hall in Ludwigshaven, Germany, which was recorded with a prototype magnetic deck made by Telefunken running BASF tape.

Sir Thomas Beecham: A Centenary Tribute, written by Alan Jefferson and published in 1979, adds nothing about the Abbey Road stereo test, but fleshes out how the BASF tape recording came to be made.

'In November 1936 Beecham took his new orchestra, the London Philharmonic, on a tour of Germany, giving eight concerts in eight different cities within nine days.

'The first concert took place in Berlin… It was broadcast all over the Reich and relayed to Britain… That night was the beginning of a round of hectic parties for the LPO… Sir Thomas danced on a table, sang songs and told a string of stories.'

A few days later 'Beecham was taken to a party at Rudolf Hess's imposing house… He sat himself down at the piano and proceeded to play. Afterwards Beecham admitted that he had been so bored that he could think of nothing better to do'.

On The Money

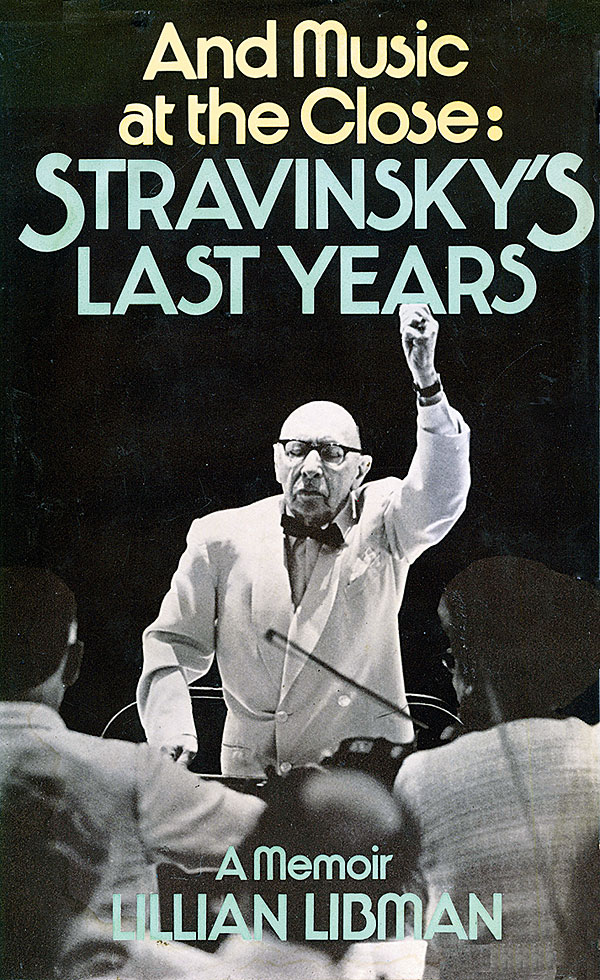

Questions abound on Stravinsky's close relationship with Robert Craft and to what extent recordings credited to Stravinsky were actually made by Craft. Music At The Close: Stravinsky's Last Years A Personal Memoir, 1972, by Lillian Libman, is a must-read on this because Libman worked closely with Stravinsky, from 1959 until his death in 1971, mainly as his personal manager.

Libman wrote: 'Stravinsky often referred to Robert Craft as "my ears"… [because] Robert has a "mechanically perfect" ear: that is, he is able to detect immediately even the slightest deviation from the printed score – a wrong pitch or rhythm rarely escapes his attention during rehearsal or playback.

'This "ear" was invaluable to Stravinsky… [and] the recording company – for a practical reason: Robert saved them money…

'As far as I know, Stravinsky did not listen to playbacks… As for editing, this was a task in which he had never involved himself.'

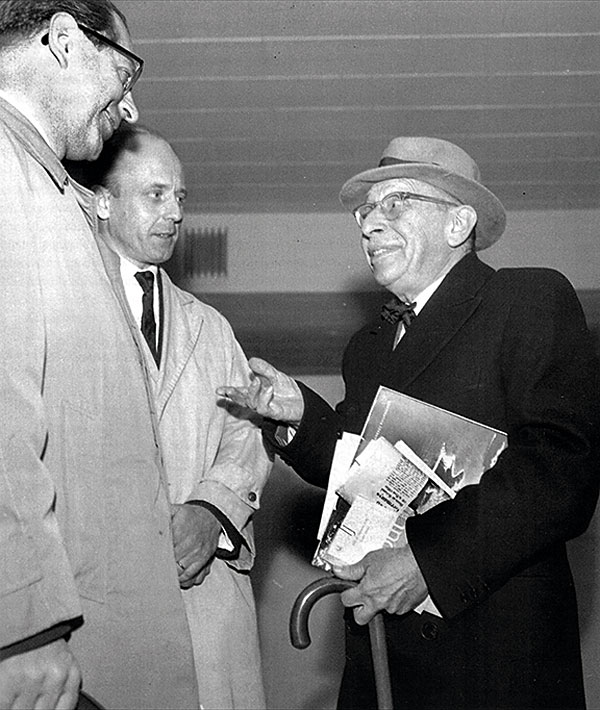

Sir Edward Lewis ran Decca with engineer Arthur Haddy and international manager Maurice Rosengarten. In the 1950s John Culshaw was recording manager and then musical director.

His 1981 biography, Putting The Record Straight, is packed with straight talk and insight, for instance why recordings made in 1951 at the first Bayreuth Festival after WW2 were not released for 50 years. Culshaw wrote: 'I felt that the majesty of [Hans] Knappertsbusch's conception [of The Ring] must be recorded… after a long argument, Rosengarten agreed that we could put The Ring on tape on the condition that no contracts to cover payment would be made until after the event…