Back In The Groove

On October the 3rd 1996, after a concert by Steve Reich And Musicians at The Royal Festival Hall to mark the American composer's 60th birthday, this writer presented him with the LP sleeve of his 1978 album Music For 18 Musicians, and asked him to autograph it. This prompted some amusement on his part. 'I haven't seen one of these in a while,' he said chuckling, 'have you borrowed it from a museum?'

Such is the way we laugh at things that have become unfashionable or obsolete – we can add brick-sized mobile phones, Video 2000 systems and MiniDiscs to the list. In the first decade of the new millennium, the joke was that if you mentioned records to a teenager they would respond with 'What's a record?'.

Pressing Concerns

But trends can come around again and in an unlikely rehabilitation of the format, young hipsters began to be spotted hunting through LP racks in secondhand record shops while older listeners were retrieving their vinyl collections from storage.

Yet few could have predicted the ubiquity of vinyl versions of new album releases in the second decade of the 21st century and the rise of so many labels that reissue albums on audiophile vinyl. Demand has risen in the last five or six years, not just for vinyl, but for the highest possible quality of materials, pressings and album sleeve artwork.

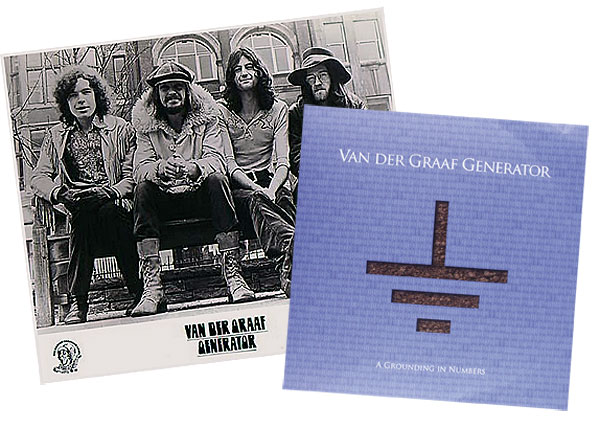

Esoteric Records specialises in reissues of '70s progressive, psychedelic and classic rock albums on 180g vinyl, though its first brand-new vinyl release was the Van Der Graaf Generator album A Grounding In Numbers in 2011. Yet apart from releasing LPs as part of box sets the label only began doing standalone reissues on vinyl in 2014 when it was sure that demand had been established beyond doubt.

'Initially with reissues, the standards of pressing left a lot to be desired, but the whole approach to manufacturing has improved,' says Esoteric label manager Mark Powell. 'I think it was imagined that people were putting them on a shelf as a kind of curio, but now it's different. High-end turntables are selling again and you have to make any vinyl as good as the original, and if you go back to the original master tapes I think that the new vinyl pressings are superior to the old ones.'

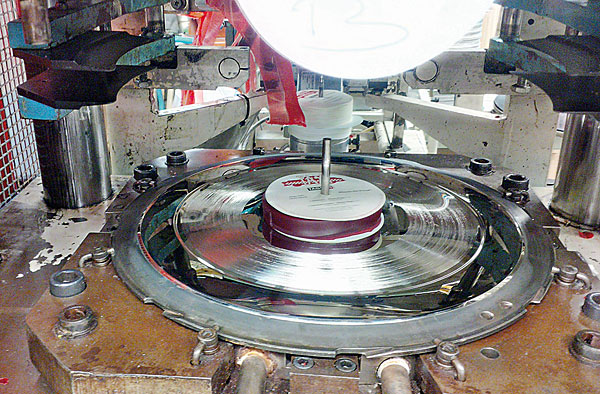

Music On Vinyl, which is based in Haarlem in the Netherlands, began operations in 2009 with 15 releases on 180g vinyl. The company was formed by Jan van Ditmarsch, the managing director of Bertus Distribution – currently the biggest distributor of physical music product in Europe – with John Burgers, and Ton Vermeulen. Ton is the owner of Record Industry, one of the world's biggest pressing plants with 33 presses and the capacity to produce up to 50,000 records per day. Van Ditmarsch reckons that makes it 'a perfect combination'.

Out On Licence

So why exactly did they start?

'Just for the love of music,' van Ditmarsch replies. 'I'm 60 and John and Ton are also 60, and I have memories of buying vinyl. I've now been working for over 40 years in the music industry. Vinyl was something special and we thought, maybe we can make a little turnover.

'I went through my collection and made a choice and saw what wasn't available. With Bertus I have daily contact with all the record companies and in meetings I told them, "Listen, is it OK to give me the license to release some of your records?". And they said yes because it was so small and they know me. They really didn't expect that it would become so big!'

During an album's lifetime it can be released on LP on different labels, which is largely down to the fact that the licences vary in length. For example, Music On Vinyl can now secure long-term licences for European releases, but other licences might last for just a few years while others are specific to particular territories.

Heavyweight vinyl has been a part of the record industry for longer than people might realise. The very first Columbia LPs of over 60 years ago tipped the scales at 220g while in the '50s and '60s it was relatively common to press LPs on heavy virgin vinyl, although with rising costs in the '70s, the use of recycled vinyl compromised quality.

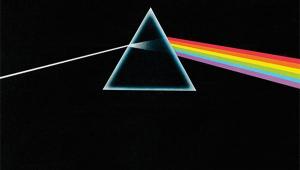

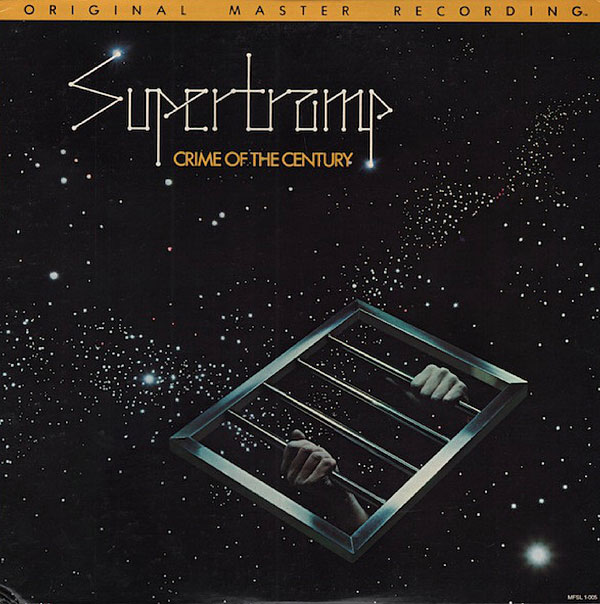

Chicago-based company Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab was founded in 1977 and launched the Original Master Recordings series, which utilised the half-speed mastering process. It released Supertramp's Crime Of The Century in 1978 and Pink Floyd's The Dark Side Of The Moon in 1979, both on three-year licenses. These reissues, which came in heavy cardboard sleeves, sold 20,000 and 30,000 units respectively. They were remastered from the original master tapes with no compression and the minimum of equalisation, and were pressed in Japan using JVC Supervinyl, which had been formulated for manufacturing quadraphonic LPs. It was more durable than standard vinyl with less surface noise.

Massive Insurance

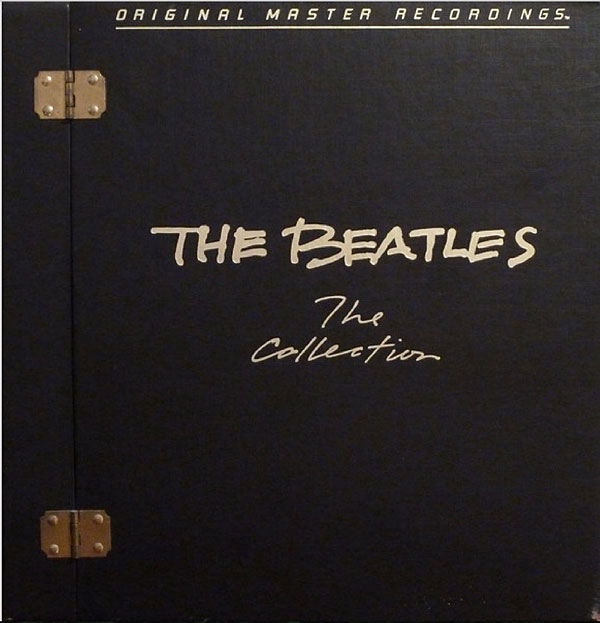

Back in 1981 the company produced the 14LP box set The Beatles Collection for which the album masters left Abbey Road for the first time. It must have been a bit like shipping the Ark of the Covenant out on loan.

Michael Grantham, MFSL's Managing Director A&R/Business Affairs explained the procedure. 'Masters were couriered by MFSL executives in lots of two to four at a time, back and forth from Abbey Road to our Chatsworth studios in California, for periods long enough to get test pressings back from JVC. Then the next batch was readied for another swap trip. We had – and still do have – a fairly massive insurance policy that covers us having masters in our possession.'

Jessa Zapor-Gray, owner of ZG Inc, which undertakes communications work on behalf of MFSL says, 'There has always been audiophile vinyl, from direct-to-lacquer cutting to high-fidelity monophonic 78s. Modern audiophile releases are defined by the time and care taken to get things right, coupled with choosing the best materials and processes available'.

These days MFSL uses the Mo-Fi SuperVinyl compound developed by the vinyl pellet manufacturer Neotech in conjunction with Californian pressing plant RTI. The compound is said to bring enhanced groove definition to pressings while reducing the noise floor.

One Small Step

Making audiophile vinyl LPs means getting as close to the master tape, sonically, as possible and trying to cut down generational loss from the lacquer to the vinyl LP.