Vaughan Williams: Tallis Fantasia

It would be hard to overstate the impact of the Tallis Fantasia on both listeners and composers of the last 70 years, for many of whom it has opened a great wooden door on to both Vaughan Williams and a wider world of music that feels spiritual in character without being tied to a particular faith or religion.

The memory of the late Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, former Master of the Queen's Music, could stand for many others: 'I heard it as a boy and thought it was just the most beautiful thing ever, which it probably is in its way.'

Very Old Or Very New?

It's instructive to remember, then, that the work's first performance caused hardly more than a few ripples. This was led by the 37-year-old Vaughan Williams at the 1910 Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester Cathedral as a prelude to Elgar's Dream of Gerontius, also conducted by its composer. Fuller Maitland was one of few early critics to grasp its special qualities: 'Throughout its course one is never quite sure whether one is listening to something very old or very new'.

As was once common with performances in sacred settings, the Fantasia was received in silence and VW took his seat in the nave. He shared his score of Gerontius with the grateful young student next to him, who happened to be Herbert Howells. The evening made a formative impact on Howells, who remembered tramping the streets afterwards with a friend, discussing not Elgar but the new piece: 'It was after then that I felt I really knew myself, both as a man and artist. It all seemed so incredibly new at the time, but I soon came to realise how very, very old it actually was, how I'd been living the music since long before I could ever begin to remember.'

Vaughan Williams was better known at the time as a compiler of folk music and old hymns than as a composer in his own right: chamber works such as the song-cycle On Wenlock Edge had not carried his name to the public at large, and the long-gestated Sea Symphony would only be premiered the following month at the Leeds Festival. The background to the Fantasia lies in his work as co-compiler of The English Hymnal (first published in 1906) and his studies in Paris: 'Of all my pupils', said Ravel, 'he's the only one who doesn't sound like Ravel'.

Intuitive Design

Probably more by intuitive accident than design, the roughly symmetrical layout of the Fantasia uncannily mirrors the architectural proportions of Gloucester Cathedral itself. The opening chords and tremolo shimmer establish a breadth of time and space and make immediately clear that what is to come will not echo the heroic-Romantic playbook of harmony and expression. There follows in the middle register a full statement of 'Why fum'th in spite', the hymn written by Tallis to set the opening verses of Psalm 2, and phrased with the combination of recitative and melisma which is particular to Anglican psalm-singing.

Then, a stroke of genius for which VW does owe something to his Classical and Romantic-era forebears from Mozart to Berlioz: a dialogue between the main string orchestra and a smaller ensemble, which at the premiere was placed behind the audience at the back of the nave. This instrumental theatre embodies the distance between the source and its transformation, between Tallis and VW, between an idealised then and a renewed present.

Beginning the Fantasia proper, around four minutes in, a solo quartet drawn from the main ensemble serves as a bridge between the two worlds, embroidering the theme and leading its flow towards a golden-section climax. The last section, also around four minutes long, returns to the declamation of the opening, though still playing with the antiphony of the three different ensembles.

Whether in mono or stereo, recordings of the Tallis Fantasia stand and fall by their differentiation between the ensembles; by the degree of space around the sound without muddying the harmonies; and by a feeling for the language of Tallis's Elizabethan age as much as the new pastoralism of Vaughan Williams and his contemporaries.

To begin with, the composer did his work few favours by suggesting a hopelessly unrealistic metronome mark which would send the Fantasia packing in under 12 minutes. Even so, its ebb and flow is alien to the elegiac dirge of Bernstein (CBS/Sony) or the Brucknerian solemnity of Haitink (EMI/Warner). Among significant early interpreters, Toscanini and Mitropoulos (on various reissue labels) both cultivate an urgent cantabile that, while exciting in itself, also misses the point of the Fantasia's originality.

All Too Seductive

Even more than his first version, still a classic Decca reissue from the 1970s, Marriner's 1983 Philips recording respects the shape of the original hymn and not just the melody. Some of the solo playing and chording is a bit rehearse-record but the spirit is all there. By contrast, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla (with the CBSO on DG) is precious and no more inside the flow of the piece than the warmer but generic mittel-Europäisch legato of Karajan (EMI/Warner) and Ormandy (CBS/Sony).

The cultivated polish of Decca's mono engineering and the Boyd Neel String Orchestra hold up well in the Fantasia's first recording from 1936, and the impassioned oratory of Boult's wartime recording will surprise listeners familiar with his stereo versions. However, the crackle and hiss of shellac can be all too seductive in its own terms, a technological analogue for the Fantasia's exercise in renewal which too readily slips into nostalgia.

Cathedral In Sound

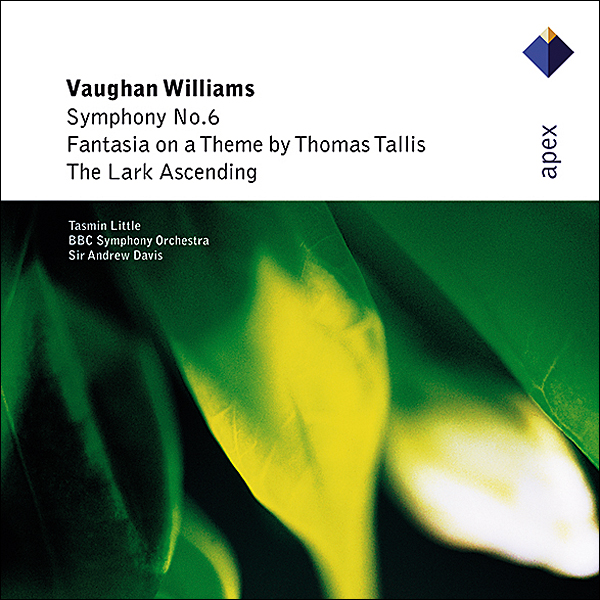

A BBC film (now on YouTube) recreated the layout of the premiere in an empty Gloucester Cathedral, and it's salutary to note how Andrew Davis's direction of the BBCSO strings is necessarily more spacious than his studio recording [see Essential Recordings below].

Davis is one of few conductors alive to have encountered VW in the flesh, as a schoolboy from Watford Grammar, going to recording sessions at Maida Vale with the composer in the balcony – 'looking very baggy and with his hearing aid in'. As Organ Scholar at King's College Cambridge, he then played daily Evensongs with the choir and Sir David Willcocks and appeared on Decca albums of Tallis and Byrd.

More directly than a Bruckner symphony, the Fantasia embodies a cathedral in sound; among modern interpreters, Davis and Manze mark out its architecture with as much confidence as their fondly remembered predecessors.