Smetana Má vlast

There's more to this hymn to Czech nationhood than the familiar strains of Vltava, says Peter Quantrill, as he explores the history of the complete orchestral cycle on record

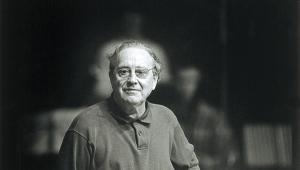

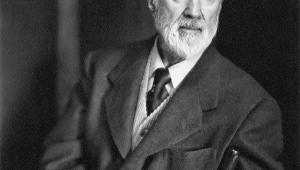

Smetana grew up speaking German and Czech, though one of these languages came more naturally to him than the other. His father recorded the news of his son's birth (in March 1824) in Czech, but named him Friedrich. The boy grew up in a German-speaking culture, not least because of his father's occupation as a brewer. The family spoke Czech at home but the young Smetana wrote his diary in German, and struggled for many years to master a 'pure' form of his native tongue.

Comic turn

This awkward bilingualism is key to an understanding of the cycle of tone-poems that established Smetana's reputation as the father of a native Czech music. After various failures to secure recognition or steady employment in Prague, he had left for Sweden in 1857. Returning home briefly in 1861, Smetana stopped en route in Weimar to visit Liszt, who had shown him kindness when he was a young composer on his uppers.

They discussed how to do for comic opera what Wagner had done for tragic and historical epics (he was in the midst of work on The Ring at the time), and the idea for The Bartered Bride was born. 'That evening', Smetana later recalled, 'was decisive for my whole life: I swore there and then that no other than I should be the creator of a native Czech music'.

The success of the Bride propelled Smetana to celebrity status, and in 1868 he laid the foundation stone for the new National Theatre building in Prague. Then his hearing began to fall him. In July 1870, he heard Die Walküre three times in Munich, yet four years later he had become completely deaf.

Smetana had already suffered more than his share of tragedy, including the deaths of his wife and three of his four daughters. Now he had to resign from his opera-house post. His replacement was an old rival who saw to it that none of Smetana's operas would be put on.

Now isolated and impoverished, the 50-year-old Smetana planned out a four-movement orchestral cycle: 'musical pictures of Czech glories and defeats'. Completed and performed the following year, this early version of Má vlast has an integrity of its own as a would-be (or even anti-) symphony. The later additions of Tábor and Blaník do more than bring a cyclical thematic unity to the final version. They round out a musical portrait of the Czech nation viewed from three contrasting perspectives: the mythical, natural and historical.

Myths in music

In this way, Má vlast became an orchestral, wordless epic drama to emulate Wagner's achievements on stage. We all know Vltava best, as a musical drawing of Czechia's longest river, running from its two sources down into Prague and towards its confluence with the Elbe. Playing or hearing the other instalments in similarly picturesque fashion, however, undervalues the breadth of Smetana's vision for the whole cycle.

The myths behind Vyšehrad and Šárka are tragic: a fortress overrun by invaders and a warrior-maiden who falls in love with her enemy before having him slaughtered. Just as the real-life Vyšehrad still stands and towers over Prague from its vantage-point, the symphonic poem serves as a perpetual reminder of a noble, much mythological native past and its often doomed attempts to retain independence.

In a related way, the nature elements of the cycle, Vltava and From Bohemia's Woods And Fields, celebrate both landscapes and rural ways of life being radically transformed by the industrial revolution of Smetana's lifetime.

Finally, the cycle's last two instalments form an extended set of chorale variations on an old hymn to retell the story of defeated Hussite warriors who retreat inside Mount Blank to await, in suspended animation, the undetermined point at which they will fight for their nation once more.

It should be clear that the overall tone and direction of Má Vást is one of tragic struggle. The Czech Philharmonic has not always played it that way. From Šejna to Neumann to Bělohlávek, successive generations of fine native conductors have fought (and not always won) to shape for themselves what feels like a collectively evolved interpretation, passed down like a much-reproduced postcard in a museum of Czech heritage.

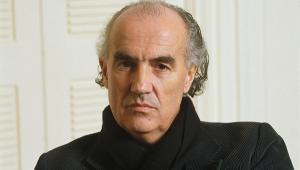

The processional and marital character of Tábor and Blank presents a particular challenge, in sustaining tension across half an hour without hustling through relatively bare pages of score; in steering clear of empty bombast while projecting pride and majesty. This is the most successful aspect of the latest in the orchestra's legion of recordings, under conductor Semyon Bychkov (on Pentatone).

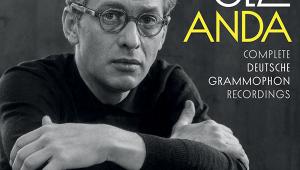

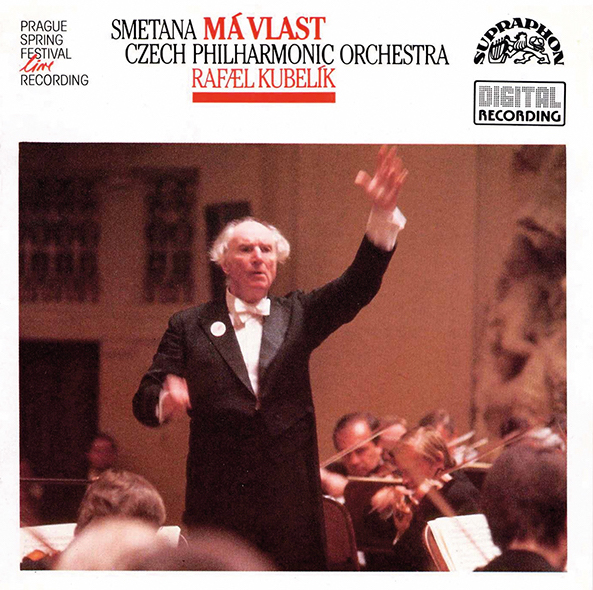

Perhaps precisely because he had not led them for half a century, the CPO responded with special alacrity and electricity to Rafael Kubelik in the famous concert recorded after the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia. Chicago 1952 (Mercury), Vienna 1959 (Decca), Boston 1971 (DG), Munich 1984 (Orfeo), Prague 1990 (Supraphon) - Kubelik's recorded engagements with the cycle amount to a history of the classical record industry itself from mono to stereo, analogue to digital, LP to Compact Disc.

The 1990 version deserves a place at the head of Má Vást on record, alongside other historic occasions [see boxout] when performances have taken on a political significance that would surely have astonished and gratified Smetana. Yet the Czech PO does not own the piece. Norrington ruffled feathers when invited to bring 'period' colours to it at the Prague Spring Festival in 1996. Rather than pure tone, it's the lack of bass and Romantic conviction to his LCP recording that tell against it.

Strings and stories

These are not complaints that could be levelled against Harmoncourt or Luks, who fields a huge string section as well as a battalion of soft-grained brass. More intriguing is that their understanding of a 'historically informed' Má Vást leads them to adopt broader templ than most of their predecessors on record. They do this in the service of story-telling: the warriors filing into Blank, Šárka's moment of regret before the slaughter, the bardic introduction to Vyšehrad like turning the first page of an illuminated manuscript.

Harmoncourt took his ideas even further with a late reappraisal in Amsterdam (which can be viewed on YouTube). Kifill Petrenko draws on his long Wagnerian experience in a fascinating 2024 concert available on the BPO's Digital Concert Hall. As the most thoughtful Czech maestro of our time, Jakub Hrůša has already documented his evolving relationship with the piece via three recordings. Má Vást is no faded set of postcards but an unfinished journey through Czech history.

Essential Recordings

Czech PO/Talich (1939)

Supraphon SU40552 (2CDs)

Complete with radio announcements and fervent ovations after each movement, in mono, burning with a sense of occasion.

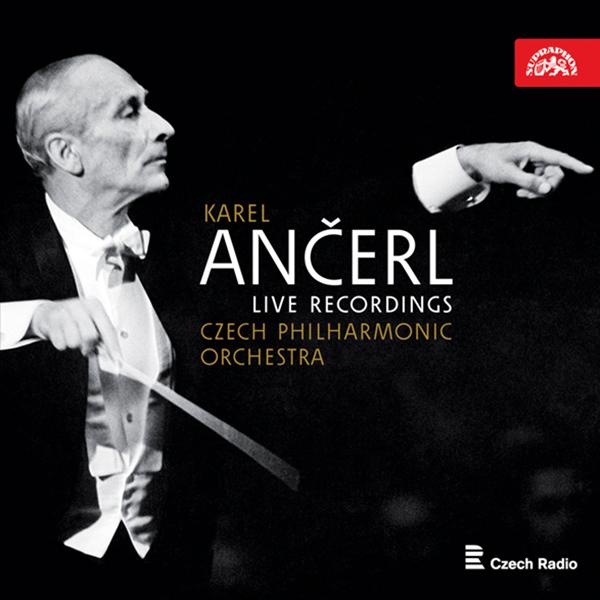

Czech PO/Anceri (1968)

Supraphon SU43082 (15CDs)

The finest Czech conductor of his generation, 'late' and live: more flowing and reflective, strong in the pastoral and poetic episodes.

Czech PO/Kubelik (1990)

Supraphon 1112082

A famous homecoming, almost (not quite) overwhelmed by emotion by the end, in dry but involving modern digital sound.

Vienna PO/Harmoncourt (2001)

RCA/Sony 82876543312

A lingering love-letter to the score, quirky in narrative detail, and the VPO kept on its toes by bold rhythmic pointing and accents.

Bamberg 50/Hrusa (2016/2020)

Tudor TUD7196 (CD), Accentus ACC40482 (3LP)

Affectionate but detailed landscape painting, with an extra dramatic tension on the later, direct-to-disc LP version (if you can find it).

Collegium 1704/Luks (2021)

Accent ACC24378

A new and refreshing take on 'authentic' Smetana: generous in phrasing and ambience, full of surprises but hardly iconoclastic.