Copland Appalachian Spring

The Gift To Be Simple’, an old Shaker tune quoted and developed throughout Appalachian Spring, could be the motto for a major part of Copland’s work. Copland could write hard-edged pieces with the best of them, and did so especially at the beginning and end of his career with works such as the Vitebsk piano trio of 1928 and the magnificent orchestral Inscape (1967). By contrast, his famous scores of the 1930s and ’40s develop an aesthetic of simplicity and accessibility exemplified by Appalachian Spring, which he composed for the dancer and choreographer Martha Graham.

Rural Living

The unassuming setting is a farmhouse in a pioneer settlement, but Graham and her company gave the first performance at the Library of Congress in Washington in 1944. Accompanied by a chamber ensemble of 13 instrumentalists, Graham herself danced the part of a newly married Pennsylvanian farmer’s wife, the completion of whose house is the focal point for a joyous celebration of American rural life in the early 19th century.

The following year, Copland expanded the scoring to full orchestra. At the same time he cut out some transitional passages and entirely omitted the appearance of a hell-and-damnation revivalist minister (danced by Merce Cunningham at the premiere), who warns the young couple about the trials that fate might have planned for them. That episode had originally interrupted the set of variations on Simple Gifts, introducing both tension and turbulence at a crucial point and making the return of the hymn-tune in the final pages that much more striking and moving.

Other hands have since orchestrated and reinstated Copland’s cuts, leaving us with four versions of varying authenticity: the full ballet in both chamber and full-orchestral versions, and his Suite in the same two instrumentations. As a measure of its immediate impact and popularity, the orchestral suite received four studio recordings within a decade of the premiere. (Could that be said of any other piece of classical music?) Conducted by names still well known (Serge Koussevitzky) and much less so (Arthur Rother, Fritz Litschauer and Howard Mitchell), these versions have long since disappeared.

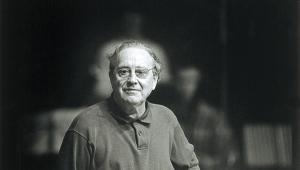

A pioneer and an authority on early music, Christopher Hogwood had an unlikely affinity for Copland

Mark of Genius

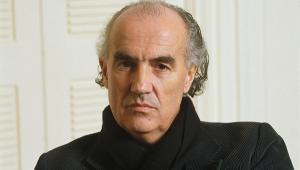

The early history of Appalachian Spring is documented instead by sonically compromised live recordings of the orchestral suite, led by Mitropoulos in New York and Celibidache in Berlin. And no, the Berlin Philharmonic of 1946 have no more idea what to do with Copland than you’d expect. Try to cast your mind back to a time when Simple Gifts was not ubiquitously familiar as an assembly hymn, a sticky ballad or a vehicle for ersatz-Celtic prancing (The Lord Of The Dance). To its first audiences, Appalachian Spring felt entirely new but comfortingly familiar – a mark of genius?

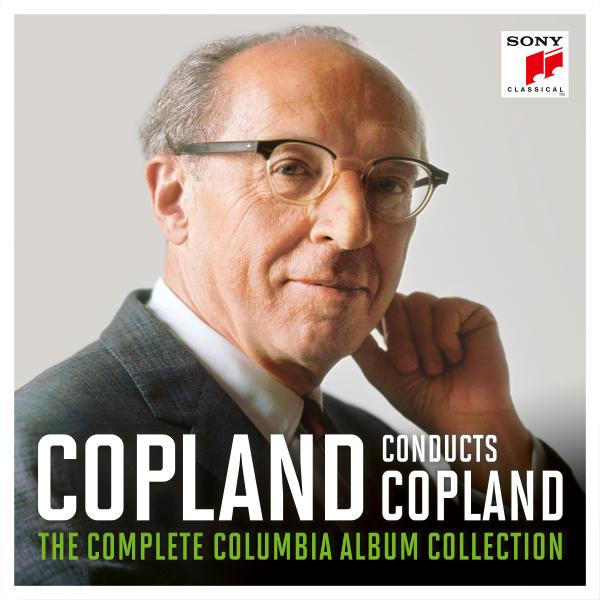

By the time the composer himself stood before a chamber group of session musicians in 1973, preparing to record the original complete ballet, he could begin by saying without false modesty, ‘I assume everybody knows this piece’. CBS/Sony left us an invaluable 17-minute sequence of rehearsal excerpts, which has appeared once more in a newly remastered box of Copland conducting Copland.

More than any strenuous analysis, Copland’s off-the-cuff comments tell you how the piece sounds, and should sound. ‘A warm, soft sound, without any sense of effort. Not too much attack on each note. Watch out that we don’t get too sentimental, it’s a little on the Massenet side. Make it more American in spirit, more non-committal. This is passage-work, Miss Graham is dancing. The music by itself is warm, you don’t have to help it. It’s not so much a loudness as a bounciness that I’m looking for. Marcato but in a playful manner. We’re not playing the Sacre du Printemps. It’s meant to be light, bouncy, happy. Amerikanisch.

ohn Wilson on Chandos: hauntingly sensitive to moments of magic.

No Guessing

All the same, Copland the conductor serially betrays Copland the composer, being rhythmically disjointed despite his best efforts and evident intentions. ‘Not together! Don’t hurry! Why is that so hard, gentlemen, don’t guess!’ The most technically polished composer-conducted account is from 1970 with the LSO, but it’s relative.

For many years, the version of the suite led by his friend Leonard Bernstein retained primacy in the catalogue. With all due acknowledgment of Bernstein’s versatility, however, was Appalachian Spring truly his kind of piece? He made two recordings of it, for CBS and DG, and never quite shook off a species of beefy extroversion and Mahlerian intensity. ‘More non-committal’ was not a phrase in Bernstein’s vocabulary.

In his own way, Copland knew exactly what he was doing, writing a half-hour folk ballet with ‘spring’ in the title. Mid-war, he spoke directly to his audience, and they heard what they needed to hear in its quiet affirmation of rural middle-American and tonal values, rooted in non-denominational spirituality. (When they needed a heroic story of perseverance and triumph a few months later, he gave them that too, in the Third Symphony). Appalachian Spring was embraced as an expression of American history and identity comparable to VW’s Tallis Fantasia for the English.

The 1958 film of Martha Graham and company opens out Copland’s score

Favourite Piece

Even more than the rehearsal sequence, the 1958 TV film (on YouTube, and a Criterion DVD) of Martha Graham’s company dancing Appalachian Spring brings the form and the gestures of the score to life. Eugene Lester accompanies with more sprightly tempi than usual, perhaps opening out some Stravinskian influence in the process (no bad thing). The painstakingly moulded modern versions by Slatkin (on Naxos) and Tilson Thomas [see Essential Recordings boxout, below] lose this narrative flow.

Back in the late ’80s, the Orchestra of St Paul under Hugh Wolff recorded the complete original version (for Teldec) with near-ideal sympathy and precision. In its continued absence, try Christopher Hogwood in Basle. There’s nothing especially authentic about the vibrato-lite playing, but authenticity cuts deeper than that.

Back in the late ’80s, the Orchestra of St Paul under Hugh Wolff recorded the complete original version (for Teldec) with near-ideal sympathy and precision. In its continued absence, try Christopher Hogwood in Basle. There’s nothing especially authentic about the vibrato-lite playing, but authenticity cuts deeper than that.

Essential Recordings

Basel CO/Christopher Hogwood

Arte Nova 82876506932

The complete ballet in the original chamber version: played, conducted and recorded with lucid, plain-speaking vitality.

San Francisco SO/Michael Tilson Thomas

Sony 82876658402, RCA 09026635112

Full ballet, full orchestra: affectionate tempi and impressionistic textures underlining Copland’s mastery of orchestration.

Ensemble K/Simone Menezes

Aparté AP243

Suite, chamber version: taps into the homespun modesty and simplicity like few others, but in high-finish modern engineering.

BBC Philharmonic/John Wilson

Chandos CHSA5164

Suite, orchestral version: the Chandos engineering brings a wide-screen panorama to the open harmonies and sturdy dances.

Pittsburgh SO/William Steinberg

DG 4864442 (17CDs)

Suite, orchestral version: no-nonsense tempi from Steinberg, analytical Command Classics sound, newly remastered by DG.

Columbia CO/Aaron Copland

Sony 19439977462 (20CDs)

Complete ballet, chamber version: dry sound, even in a new remastering, patchy execution, but imbued with unique authenticity.