Géza Anda Troubadour of the Piano

When ‘contact hours’ are meanly doled out to students with a teaspoon – here’s your two-hour seminar for the week, don’t enjoy it all at once – the kind of education and formation which Géza Anda underwent in 1930s Budapest would be unimaginable to young musicians today.

Born in Budapest in November 1921, Anda enrolled in the ‘gifted children’ division of the Franz Liszt Academy at the age of 13. In fact the school had been known to take prodigies as young as eight, presumably on the basis of the wisdom later distilled by Sir Matt Busby: if they’re good enough, they’re old enough.

Solfège to symphony

In addition to their principal instrumental tuition, all students at the Academy took the following subjects: solfège, harmony, theory, form and analysis, viola (to learn to play inner voices), conducting, music history, Hungarian folk music (with Zoltán Kodály), chamber music with piano (with Leo Weiner), and orchestra. Many of these classes took place on a daily basis.

Anda learnt piano with Ernő von Dohnányi in afternoon-long lessons, three times weekly. On top of all this, several hours of daily private practice was expected as standard. Perhaps such a schedule looks punishing. It would not suit anyone less than fully committed to music as a vocation, as well as a profession.

What this education produced was complete musicians, Anda among them, not mechanical virtuosos. To analyse and to perform a score were not distinct but complementary endeavours. The Hungarian system also produced teachers: Anda, and fellow students such as Andor Foldes and Annie Fischer, went on to become the Dohnányis of their generation, though firstly war and then authoritarian rule scattered the Budapest students of the ’30s to the four winds.

Above: Meeting of minds (l-r): Fournier, Schneiderhan, Fricsay and Anda at the DG sessions for Beethoven’s Triple Concerto

Anda escaped Horthy-era fascist rule in his native land by moving to Berlin – out of the frying pan into the fire. It was Wilhelm Furtwängler who came up with the ‘troubadour’ tag after they played Franck’s Variations Symphoniques together, but perhaps a more consequential performance had already taken place, when Willem Mengelberg conducted the newly graduated Anda in Brahms’s Second Concerto.

The piece became Anda’s talisman. In addition to the ’60s studio recordings with firstly Fricsay and then Karajan, there are live recordings stretching into the double figures. So many pianists of our time sound ponderous and arthritic by the side of Anda, confusing heroisim with sheer force of fingerwork. And it’s not merely a matter of tempo. Anda’s rhythms are spring-heeled, his phrasing speaking to itself as well as to the orchestra.

Bartók’s best

In this regard, the 1960 version with Fricsay stands up as the finest analogue-era recording of the concerto, and a fine example of the BPO in their transitional era between Furtwängler and Karajan. Anda and Fricsay worked together with a special native affinity. For decades their Bartók concertos album had definitive status, and it still ‘speaks Hungarian’ with a special fluency. But then Anda’s formation had taught him that everything he played belonged to a grand tradition, one which had evolved in an unbroken line from Bach up to his own time – Bartók had been another teacher at the Liszt Academy. Anda, together with his colleagues, never suffered from a paralysing sense of intellectual rupture between the Romantic and modern eras.

Above: Lessons in Brahms (1): Géza Anda (right) at the piano with Herbert von Karajan

While it would be a stretch to claim that Anda’s own repertoire was adventurous, he worked best with conductors of questing intellect, though their interpretative approaches could be poles apart. It’s hard to think of conductors with less in common than Karajan and Boulez, Knappertsbusch and Ernest Bour, and yet they all (like Furtwängler) found in Anda the kind of fierce and lively musicianship that would put them on their mettle.

‘Conductors are not trained, they are born’, Anda reflected in a 1965 interview. ‘I have played with many of the world’s first-rate conductors, and many of the second-rate and the third-rate. From this, you learn. And after all, what is a symphony but an orchestrated sonata?’ This thought process had led him to conduct Mozart from the keyboard. Over the course of the 1960s, and not in a rush but album by album, he recorded the first-ever cycle of concertos done this way.

In the movies

A personal aside: it was through Mozart, and the Concerto No. 21 K467, that I first heard Anda’s playing, on my first classical cassette (a gift from my parents on my eighth birthday, along with Abba’s Super Trouper and 1982 by the Quo – don’t judge me). This is hand-in-glove Mozart, where the Salzburg Mozarteum complete Anda’s sentences. Countless others had made their own formative encounter with Mozart, when the same recording was used as the soundtrack to Bo Westerberg’s film Elvira Madigan in 1967.

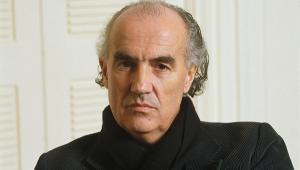

Above: Lessons in Brahms (2): with Rafael Kubelík (right), who led a good studio Grieg (DG) but another live Brahms 2 (Orfeo) for the ages

The moody sentimentalism of this movie has dated. Anda’s Mozart has not. He explained why he had taken the plunge to direct from the piano. ‘Why shouldn’t I conduct? It is only the 20th century that says a man must do just one thing. Now if you have a pain in the left side of the heart you go to one doctor, and if it is on the right side you go to a different doctor. But look at Liszt. He composed, he played, he conducted, he taught, he transposed – he thought no one would know Rigoletto, for instance, so he wrote the Rigoletto Paraphrase. His letters fill up 25 volumes, and [added with emphasis] he had an amazing number of women.’

Tales over turmoil

The quote seems to capture Anda in a nutshell. Some found his Liszt B minor Sonata too restrained, insufficiently possessed by a spirit of the demonic. Yet I think it tells a story from the first bar to the last rather than heaving around in paroxysms of musical hypertrophia. He was a musical rationalist, which also brought a remarkable consistency to his playing in the studio. ‘I want to hear on tape what I hear in the hall. I don’t want the engineer to play around with the controls to bring up the bass, for instance. It is none of his business!’

He referred to the coupling of the Schumann and Grieg concertos he had made with Kubelík. ‘We spent, for the Schumann, four and a half hours for rehearsing and recording, and for the Grieg, three and a half. This is the way I think recording must be done: all in one piece.’ All the same, Anda’s almost-annual Salzburg Festival recitals, as reissued by Orfeo, catch fire in their embodiments of Chopin, Schumann and more. The last of them is listed below as a representative sample, along with examples of other Anda collections on other labels.

Essential Recording

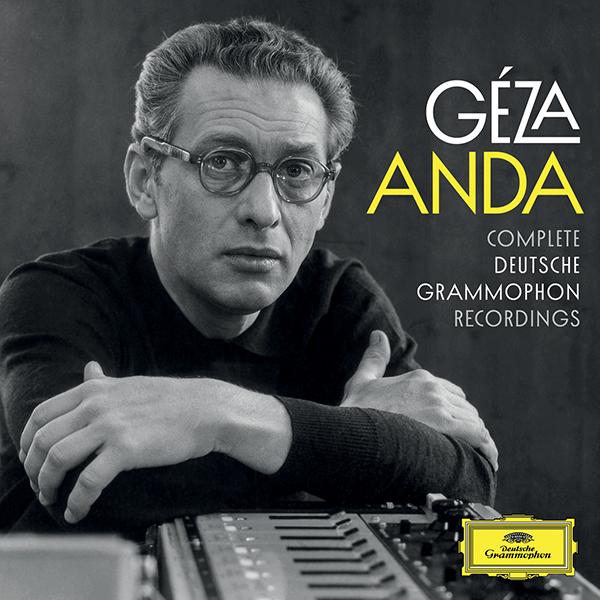

Complete DG Recordings

DG 4860502 (17CD)

Most of Anda’s classic studio albums in one handy box, including the Bartók and Mozart concertos sounding as fresh as ever.

Salzburg Recital, 1975

Orfeo C742071B

Anda’s last festival recital, at the height of his powers, with a hypnotic Chopin Second Sonata and coruscating Schumann Carnaval.

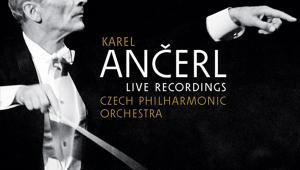

Bartók: Concertos 1 & 2, Contrasts, Sonata

Audite AUDITE23410

A dazzling partnership with Solti in the Sonata for 2 Pianos and Percussion, and a non-stop, full-on First Concerto led by Gielen.

Brahms No.1, Mozart No.17 Concertos

Prospero PROSP0100

A white-knuckle ride through the Brahms, guided by Böhm in 1963, and an Op.117 Intermezzo encore of simple perfection.

Brahms No.2 Concerto, etc

Archiphon ARC-WU224

Live with Klemperer in Cologne in 1954, a red-hot live alternative to his celebrated studio versions with Fricsay and Karajan.

Ravel Left-hand, Mozart Nos. 17 & 23

Hänssler 94216

Ernest Bour and Hans Rosbaud make complementary, analytically minded partners to Anda at his most lyrical and spontaneous.