Peter Schreier Storyteller supreme

Peter Schreierx was born into music, and into Bach. The son of the Kantor of Meissen (the Saxon town known for its porcelain), he took music lessons from his father, who recognised that his talent would blossom more fully in nearby Dresden. As an alto in the Kreuzchor, under Rudolf Mauersberger, the boy Schreier made his first solo recordings, reissued on CD by Deutsche Grammophon and Berlin Classics.

The diction, the centred tuning, the apparently natural musicianship that made him so outstanding in the fields of Bach and Lieder: these qualities were all there from the beginning. Some listeners found Schreier’s voice dry, and compared him unfavourably with Fritz Wunderlich, five years his senior. Wunderlich’s tenor was always more honeyed, though not more elegant in phrasing. If Schreier’s Evangelist had a precedent it was in Karl Erb, who brought such dignity and drama to the role under Willem Mengelberg in Amsterdam.

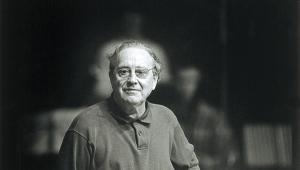

Above: The tenor made some of his first song recordings in the 1960s accompanied by the pianist Walter Olbertz

Direct line

Schreier’s Bach possessed a core of personality that radiates from recordings made throughout his near 50-year career. The Bach styles of Mauersberger in Dresden, Herbert von Karajan in Berlin, Helmut Rilling in Stuttgart and Karl Richter in Munich, were no less contrasting than (say) Gardiner, Jacobs and Herreweghe in our own time. Yet within half a phrase Schreier established in each case his own relationship with the listener, through his direct declamation and that inimitably crisp, piercing tone.

Passion play

I saw five Bach Passions with Peter Schreier – four St Matthew, one St John – and all were unforgettable. He did not so much sing the Evangelist and conduct the ensemble (although he did both, at the same time) as embody the work, and emanate it from within. When a student bass soloist in a London church lost his place mid-aria, Schreier seamlessly took over for a couple of bars.

In Rome, with much larger forces, he commanded the stage of the old Auditorium Conciliazione from the centre. Allowing himself once more to be conducted in the St Matthew, by András Schiff in the Royal Festival Hall, he gently shaped the expressive arc of the whole from the side of the podium. At such moments, he was the nearest thing to Kapellmeister Bach reincarnated.

Above: Norman Shetler was Schreier’s most regular accompanist for east-German recordings made in the 1970s

Such remarkable feats of memory and artistry are inconsistently preserved on record. The Philips versions made in Dresden are comparatively bound both by the dictates of the recording studio, and by a ‘Bach style’ which now sounds rhythmically set in its ways compared to modern, more chiaroscuro period-instrument accounts. They breathe an authentic spirit of Bach all the same, because Schreier instils into his choirs and colleagues the virtue of clarity: singing which places the text first as he always did.

Voice of distinction

More charged with the moment, the eruptive drama and tightrope lyricism which I recall in concert, is a live 2001 account from Cagliari [Dynamic] but the other soloists are not on the same level (how could they be?) and the opera chorus is sui generis. Then there is the 2018 version of Rondeau Production, recorded live at the Thomaskirche and led by Schreier once he had definitively retired from singing, not long before his death, aged 84, on Christmas Day in 2019.

Some readers might be less obsessed than I am with Peter Schreier’s Bach and will want to be reminded what else he could do. Lieder, of course, even if those who had heard Fritz Wunderlich live found Schreier wanting in the intimacy of that relationship: sturdy and sometimes four-square. But I wasn’t there, and anyway the more relevant comparison, it strikes me, is with Peter Pears, for their insistence on textual clarity as well as distinctive timbre.

Recorded first with Sviatoslav Richter and then Schiff, these two Winterreisen present a fascinating study in contrasts, and complementary musicianship. Schreier had learnt the cycle with and from Richter, and presents a wanderer alienated and resigned to his fate from the off, a complement to the sublime melancholy of the pianist’s approach to the late sonatas. As well as the live Philips version from the tenor’s spiritual and physical home of Dresden, Schreier collectors now have an eerily resonant alternative, recorded by Melodiya in Moscow during the same tour in 1985.

Tailor made

With Schiff, Schreier explored more lightness of touch, more everyday humanity to complement their recordings of Mozart and Beethoven as well as the other Schubert cycles. Recorded live in Salzburg (reissued on Orfeo), their Schumann dates from a less self-conscious age in performing this music; hardly less sophisticated in delivery, but Schreier was not an ironist. He had no use for the musical raised eyebrow or knowing wink.

Accordingly, his operatic roles conformed to the kind of tenor characters who tend to get taken for a ride by baritones. Belmonte, Ferrando, Ottavio, Tamino: all Mozart roles seemingly made for Schreier’s fine-spun, high-lying lyricism. Schreier sang David (Die Meistersinger) and Loge (Das Rheingold) with equal mastery, but the kind of dramatic agility of gesture demanded by Wagner was foreign to him – whereas his Young Sailor in Bohm’s celebrated Bayreuth Tristan is perfectly in tune with the metaphysical intensity of the whole.

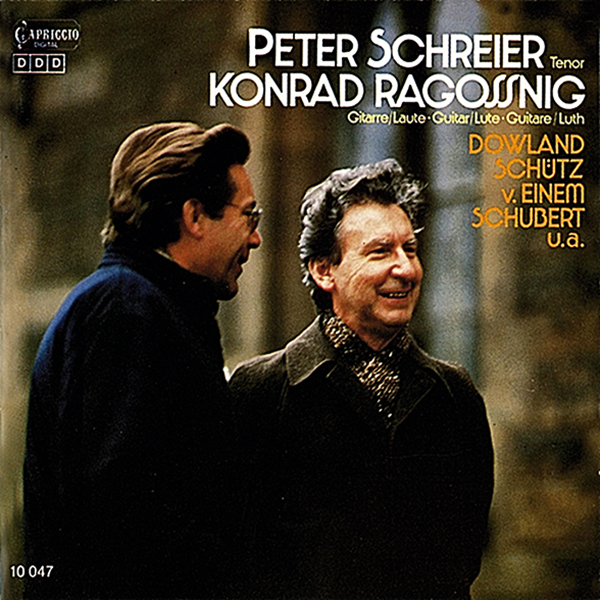

Above: Peter Schreier and guitarist/lutist Konrad Ragossnig shed new light on familiar songs in this set for Capriccio

Perfect partners

He conducted Figaro and Don Giovanni, too, but his recordings in that capacity are almost exclusively sacred. He moulded lively accompaniment for Soile Isokoski on an Ondine recital of Mozart arias, and the same label captured a late Schubert Mass more responsive than the Philips albums of Mozart such as the Requiem. One intriguing instrumental exception is a Schubert Unfinished from Dresden, interpretatively ‘central’ and rhythmically sturdy but articulated with fiery attacks – just like his singing, in fact.

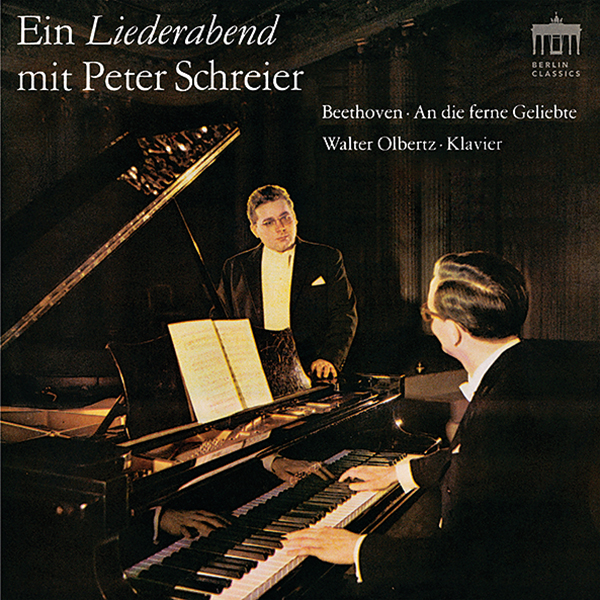

In song, alongside Schiff, Schreier enjoyed long partnerships with the pianists Walter Olbertz and Norman Shetler, and the guitarist Konrad Ragossnig. Die Schöne Mullerin from 1979 is the epitome of Schreier’s art, and Schubert with guitar has a distinguished lineage stretching back to the composer’s time. He lives every line. With him we see the endlessly turning mill-wheel, we see the particular green of the linden tree’s leaves, we feel the ground beneath our feet as well as the gradual self-awareness of innocence lost. A Schubert Top 10 would not be complete without it.

Essential Recordings

JS Bach: Choral Masterpieces

Decca 4785564 (12CD)

A one-stop-shop for most of Schreier’s digital-era Philips/Bach recordings in Dresden, including the Passions and B minor Mass.

Mozart: Arias from Così, Don Giovanni, etc

Berlin Classics 0300754BC, 0300753BC (LP)

A 1969 Dresden recital conducted by Otmar Suitner, capturing Schreier’s lyrical portraits of the ‘young-lover’ Mozart tenors.

Schubert: Winterreise

Philips 4423602

The famous partnership with Sviatoslav Richter: an unlikely but unforgettable encounter, caught live in Dresden in 1985.

Schubert: Schwanengesang, etc

Wigmore Hall Live WHLIVE0006

More remarkable live Schubert, this time with Sir András Schiff, even more bitingly intense than their Decca albums.

Schumann Lied Edition

Berlin Classics 0302928BC (5CD)

Schreier working hand in glove with Norman Shetler to bring out the youthfully carefree element in Schumann’s song-setting.

Bach, Dowland, Schütz, Einem & Schubert

Capriccio C10047

A sampler of Schreier’s partnership with the guitarist Konrad Ragossnig, and an astonishing display of stylistic versatility.