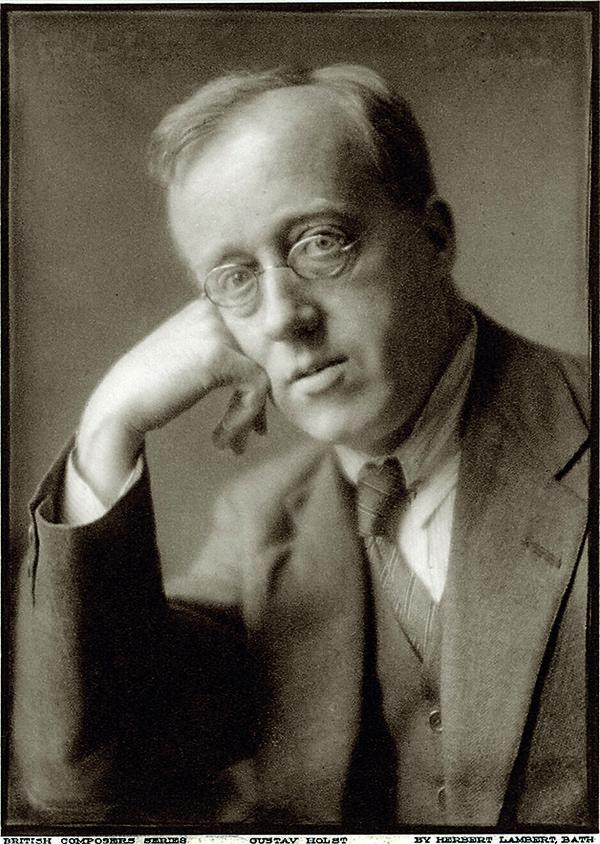

Gustav Holst The Planets

Mars sets the tone for any Planets, live or on record. Under the composer's baton in 1926, it establishes aggressive intent from bar one. War is not on the horizon, but advancing over the next hill. By contrast, the recent BRSO/Harding version (BR-Klassik) builds up menacingly, around a fifth slower, towards an implacable evocation of a war machine.

The Royal

Festival

Hall may not

be an easy

recording

acoustic, but its

analytical clarity

complements

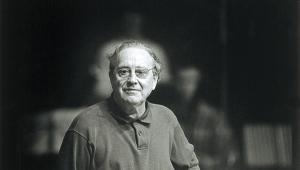

Jurowski’s pacy

conducting

The Royal

Festival

Hall may not

be an easy

recording

acoustic, but its

analytical clarity

complements

Jurowski’s pacy

conducting

Tempo Tug-Of-War

Two such different visions of the piece don't compel us to decide which one is 'right'. Holst left no metronome marks on the score, just plain old Allegro for Mars. Nonetheless, we might ask ourselves which one more closely resembles what Holst had in mind. The answer would seem to be obvious - his own recording! - except it has often been said (to justify a slower performance) that Holst had to conduct the piece more quickly in order to squeeze it on to a 78rpm record.

This is, in fact, nonsense. Columbia released The Planets on seven separate records, over the course of almost two years (imagine waiting for Neptune!). Each movement occupied two sides of the 78, except Mercury, which fitted on a single side. Venus is the longest movement of Holst's recording, at 7m18s, so he could have taken a full minute longer over Mars, if he had wished. But he didn't.

If you are used to slower versions - and most recordings of Mars take just over 7 minutes - then Holst's version can resemble one of those speeded-up old films. It has even been said that Solti (for his LPO recording on Decca) unwittingly copied the slowings-down that Holst made for side-breaks. Again, this is idle criticism. Also with the LPO, Jurowski emulates Holst's velocity in Mars (and almost everywhere else), but he generates unstoppable momentum along the way. Then he pushes straight on to the euphonium-led second theme, bringing to the mind's eye a red-cheeked general barking orders on some corner of a foreign field.

Jurowski is drawing upon superior technical finesse on the part of both 'his' musicians and engineers. Also, I venture, on his own considerably more practised technique as a conductor. Holst knew what he wanted, and how to get it, but he was not equipped to achieve the little swells, the niceties of balance, the punctuating pause and whiplash attack that set aside the best Planets performances from the rest.

At least Holst could conduct in 5/4, a notoriously tricky time-signature. Try marking it for yourself in Mars, 1-2-3-1-2, without getting tangled up. I am suspicious of the old story that Karajan was one of those celebrated maestros who couldn't 'do' 5/4 - he seemed to manage Elektra OK - but you can still hear some of the tape joins in the VPO Decca recording.

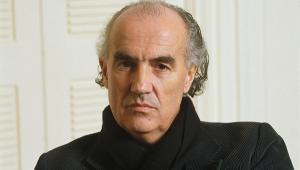

Stokowski

(pictured

here in 1932)

had been a

student at the

RCM in London

at the same time

as Holst

Stokowski

(pictured

here in 1932)

had been a

student at the

RCM in London

at the same time

as Holst

Some Like It Hot

More pertinently, Karajan never did the piece live, he takes little care over intonation (the euphonium solo is awful), and he has no feeling for the more quintessentially English elements of the piece. That means, of course, the middle section of Jupiter. It's worth emphasising that Holst did not write 'I vow to thee, my country' - British diplomat Cecil Spring-Rice did that, using Holst's tune.

The original score couldn't be clearer: non legato. And Holst's LSO play it that way, with a stiff upper lip, and little pauses after each phrase. If only more conductors had followed Solti's example and listened to the composer's version! Instead, they pour hot fudge sauce everywhere.

All the same, just as there is a plausibly slower and heavier way to perform Mars, so Jupiter can respond to a broader, more emotive approach. American orchestras and conductors often bring it off: Stokowski with the NBC [see Essential Recordings, opposite] Mehta in LA, Steinberg and Ozawa in Boston - and John Williams with the Boston Pops. All fine versions, and bringing to the country-dance theme of the first section a flavour of Thaxted goes to Hollywood.

Foreign-born players and conductors often gain in fidelity to the score of The Planets what they sometimes lose in familiarity with the idiom of this or that episode. In any case, Holst's contemporaries tended to regard him as not a 'proper' Englishman owing to his name and part-German ancestry. There is nothing very 'English' about the composer's interests in astrology and theosophy which underlie the conceptual scope of his suite.

Planetary Influences

Nor is the score itself terribly English, borrowing from d'Indy and Florent Schmitt, while partially deriving the cumulative power of its true slow movement, Saturn (the composer's favourite movement), from the melody of the Russian-Orthodox Kontakion for the Departed. The most potent influence on The Planets, though was the Five Pieces for Orchestra by Schoenberg, which Henry Wood had premiered at the Queen's Hall in London in 1912, two years before Holst began work on Mars (some months before the outbreak of the First World War).

Just as Schoenberg later taught the basics of harmony and orchestration to many Hollywood film composers, so The Planets went on to exercise a formative influence on composers for film from Vaughan Williams to Hans Zimmer. An understanding of the suite in the context of this lineage comes more naturally to some conductors than others. Boult gave the premiere, and made several recordings, but there is a sobriety and studied neutrality to them (the opening of Jupiter, for example, never really dances) that contrasts with the approach of his more flamboyant (and serially under-rated) contemporary, Sargent.

In this context, the LPO version led by Bernard Herrmann is surprisingly lifeless. Colin Davis and Slatkin notwithstanding, Andrew Davis is the best Planets conductor among Boult's and Sargent's successors at the helm of the BBC Symphony Orch. His Teldec and Chandos recordings are also superbly engineered - no small consideration in the endlessly absorbing details of Holst's orchestration, as well as the challenge of recording the off-stage chorus in Neptune.

English critics were sometimes uncomfortable with the very success of The Planets - too accessible for its own good - and the composer felt understandably aggrieved that he had moved on, but his public had not moved with him.

Break The Ice

The lasting power and imagination of The Planets, though, shines through the mono-broadcast sound of Stokowski conducting the NBCSO, and this would be my own desert-island performance, closely followed by Jurowski with the LPO. In their hands, Venus and Saturn attain a kind of intensity adjacent but not identical to contemporary scores by Korngold and Mahler. Stoki draws out the icy reaches of Neptune, and the chorus cuts off at the end after two bars. Well, nothing's perfect.