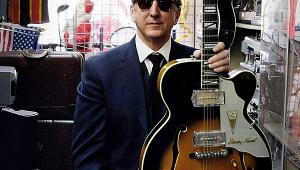

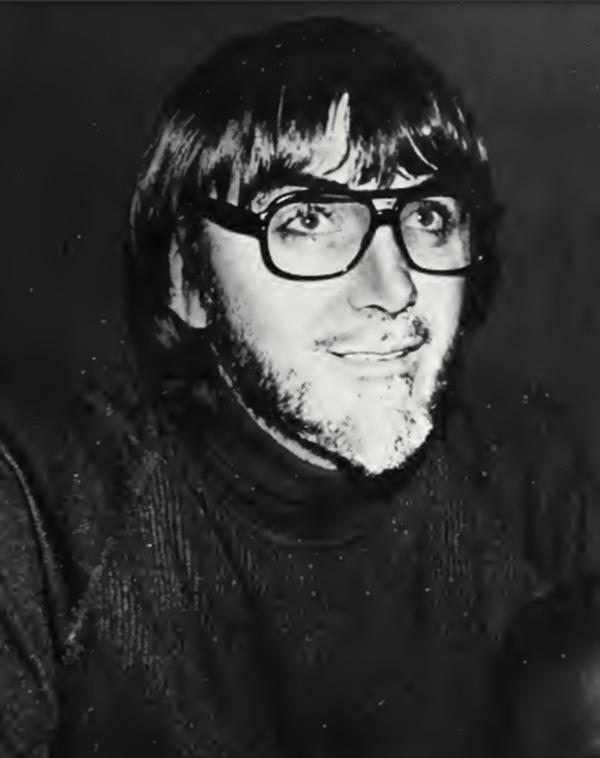

Tom Dowd

'I had no finished songs, no real concept or idea of where I was going, nothing but an abstract burning passion for live, spontaneous music. On top of everything else, I refused to make the record under my own name, and was developing a powerful drink and drug problem – not a great position for any record producer to be placed in, but [he] pulled it off.

'He saw the potential and exercised the most incredible patience in getting through the obstacles that I would constantly place in front of him. It's little wonder that I eventually came to look on him as a father figure… There is a tribe of musicians, spread all over the world, who have been fostered and nurtured by him.'

Eric Clapton delivered this speech in 2002 on the occasion of Tom Dowd being awarded the Grammy Trustees Award, which recognises significant achievement in the music business by non-performers. The project he refers to was Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs, as good an entry point as any into Dowd's career as an engineer, producer and innovator par excellence.

Clapton was holed up in Miami busily working up an acquaintance with heroin, trying to deny his personal demons, escape his celebrity and moping over Pattie Boyd, who just happened to be married to one of his best buddies, Beatle George Harrison. He was, in short, a mess. But he'd managed to round up a crack bunch of similarly wasted musicians and Dowd, who'd expertly engineered Cream's Disraeli Gears [HFN Mar '15] and Wheels Of Fire, was now the best placed producer in the world to deal with a situation where pretty much every member of the band was a boss player in his own right, having worked with the multiple talents in The Allman Brothers Band on Idlewild South.

Pretty Poly

'The Allman Brothers needed a disciplinarian more than anything else,' he recalled. 'First off, it's unusual for a band to have two drummers. It's also unusual for a band to have two lead guitar players as good as Duane [Allman] and Dicky Betts. Much of what I did was simply ironing out the polyrhythmic confusion that often existed as a result of those two guitars and two drums. Now you can't just go in there and say to them, "You play this and you play that", you have to put it diplomatically. It would be more like, "Why don't each of you take turns on that lick, and then that will make room…" etc.'

In fact, it was Dowd's idea to bring Duane Allman into the Miami mix. The Allmans happened to be playing a gig down there. Clapton was in awe of the sensational solo Allman had supplied for Dowd at the end of Wilson Pickett's version of 'Hey Jude', so Dowd took him to the show, the guitarists hit it off, and the world was blessed with Derek And The Dominos' Layla, one of the best albums to come out in Clapton's, and just about anybody's, lifetime.

Dowd, a native New Yorker, had gotten his start in the late 1940s when he answered an advert in The New York Times looking for a summer studio intern. He'd just come out of the military and a spell working in the physics department at Columbia University, a job which touched on the Manhattan Project and the development of the nuclear bomb. What he swiftly realised was that there were no proper recording engineers per se, and the equipment and studios were, as he puts it, 'hand-me-down radio equipment' operated by 'radio engineers working extra time or relegated to doing recording instead of radio broadcasts'. As he said later: 'the recording technology as a whole that existed in those days was easily within the grasp of any training I ever had with my engineering and my physics. I knew that I could make a career out of this business and have a thoroughly pleasant time the rest of my life with it'.

Crazy Cool

And so he did, joyously messing with the established recording methods and breaking rules left, right and centre, gaining the trust of the era's toughest jazzers with his eccentric new techniques. 'They'd think I was crazy at first. I'd listen to a quintet or something like that, and I'd say, "I need a mic by the piano – he's got a solo. And I'll put this mic up for the horns. And ask them to step in and out when they're going to solo. I got a bass player and a guitarist – put a mic between the two of them and then adjust their dynamic".

'And all of a sudden, when we played back the first acetate, they're looking at each other and saying, "Hey, that's cool".

I got along famously with them. There was little or no dialogue that was like, "Man, what the hell are you doing?". It was, "Hey, can you do this?!".'

As fate would have it, Ahmet Ertegun, the head and founder of Atlantic Records, was recording at Apex, a recording studio in New York, and working with a 'German professor' who he'd been told was the best in the business. Ertegun wasn't so sure. The 'professor' was a stickler for etiquette and wouldn't allow the engineers to turn up the bass or drums 'too loud' for fear that, in the pressing, they would cause the needle to jump. As it happened, the 'professor' was unavailable for the next session and Dowd was assigned as his replacement, somewhat wet behind the ears but unafraid, quickly setting up multiple mics on sources and tracking the bass and drums so listeners would be able to both hear and feel them.

Man With A Plan

Ertegun was impressed by this adventurous youth and Dowd was invited to become one of Atlantic's in-house engineers, working alongside Ertegun himself and fellow genius producer Jerry Wexler. In 1958, Dowd was put in charge of building Atlantic a new studio fit for purpose, and he had a plan.

A big fan of guitarist Les Paul's records which featured five guitars and three vocal overdubs, he couldn't figure out how Les was doing it until he learned that the records were made on an eight-track recorder. Dowd convinced Jerry Wexler to purchase the second Ampex eight-track tape recorder ever manufactured, which immediately put Atlantic's technologiy ahead of other studios for many years to come.

'I was the laughing stock of the industry,' he said, looking back. 'But from the time that machine arrived until about 1962, I saw every other record company and studio in the country go through the painful process of going from two-track to three-track to four-track. Every year, they'd write the equipment off and go up another track. Ultimately, they all went to eight-track anyway. We just took a shortcut.