Sviatoslav Richter: Pianist

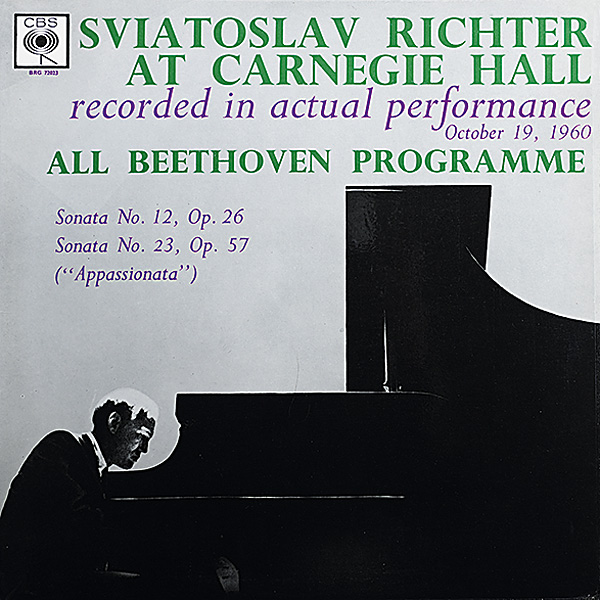

Wait until you hear Richter' was the reaction to praise when Soviet pianist Emil Gilels made his 1955 States debut. And whereas he and violinist David Oistrakh both performed with American orchestras that year, audiences had to wait a further five before the authorities allowed Gilels' Ukrainian colleague to appear at Carnegie Hall, New York, and in Boston and Chicago.

Before that Sviatoslav Richter had travelled to play in Bucharest, Prague, Budapest, Warsaw – and even in China. In 1958, he recorded concertos by Mozart, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov, and Schumann with the Warsaw Philharmonic under Witold Rowicki and Stanislaw Wislocki (produced by Polskie Nagrania and issued here by DG). But it was Richter's 1957 Schumann recital disc with the Op.12 Fantasiestücke and Waldszenen [DG DGM 18355], taped at the Prague Rudolfinum in Nov '56, which first focused Western attention on his exceptional talents.

In a televised homily pianist Glenn Gould (for some reason speaking in pure English RP, with no trace of his native Canadian) nominated Richter as the exemplar of 'a musician intent on bypassing the mechanism of the instrument to create a direct link between himself and the score', helping the listener to feel at one with the music rather than the performance per se. Artur Rubinstein said hearing his Ravel had moved him to tears.

The gentle Soviet and Russian conductor Rozhdestvensky, who only accompanied Richter in two concerts, found that he was 'Too powerful for me, he had a kind of energy which tended to crush you rather than help you collaborate'.

Sviatoslav Richter was born in 1915 to musical parents (who would later separate, his father executed for alleged espionage in 1941) and early on showed an interest in both painting and music. His father gave him some basic lessons but the young Richter was largely self-taught as a pianist until, aged 22, he went to study in earnest with the great Heinrich Neuhaus. At the audition Neuhaus declared him 'a genius – the pupil I'd been waiting for' but later feared he'd taught him nothing, although Richter himself said he learned how to master tone.

Prokofiev Premieres

Prokofiev was sufficiently impressed to allow him the April 1940 premiere performance of his Piano Sonata No 6 and No 9 – also dedicated to Richter. (Richter deplored the composer's constant denigration of Rachmaninov's music. 'Why? Because he was influenced by it.') Richter's one appearance as a conductor came in Feb '52 when he premiered the Prokofiev Symphony-Concerto dedicated to cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who played like a man possessed.

Richter was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1949 which led to international tours and was later declared 'People's Artist'. (He liked to elude his 'minders' when abroad, slipping out into the city streets at nightime.) When he met his future wife the singer Nina Dorliak, at a memorial service in 1943, he was sleeping under Neuhaus's piano and then living in shared accommodation. A week after he introduced himself to her he had moved in and they were together for 55 years.

Richter's first London visit was in 1961, when the Manchester Guardian critic Neville Cardus thought him 'provincial'. Liszt Concerto performances with Kondrashin and the LSO were recorded at all-night sessions at Walthamstow Town Hall with Wilma Cozart and Robert Fine for Mercury/Philips. In fact the early 1960s found him on RCA, DG, EMI and Philips labels. Notable releases included the five Beethoven Cello Sonatas with Rostropovich and the legendary Feb '58 Sofia recital with Mussorgsky's Pictures At An Exhibition, Liszt's Valses Oubliées and Feux Follets, etc.

At that time he met Benjamin Britten, and they began playing together at Aldeburgh and with Rostropovich. In 1970 they recorded Britten's Piano Concerto at Snape Maltings [Decca 417 3082] but a far more gripping live version from May '67 appeared on the Russian Revelation label, with Svetlanov accompanying [RV 10060].

Richter intensely disliked his 1960 Chicago recording of Brahms's Piano Concerto No 2 with the Austrian-born American conductor Erich Leinsdorf accompanying [RCA LSC2466]. Though it received critical acclaim, he preferred instead his EMI remake a decade later with Maazel and the Orchestre de Paris – a distinctly stodgy alternative.

Late in life his recitals involved having the house lights dimmed with a small lamp placed near the keyboard, Richter mostly reading from scores. At the end, he'd stand chastely with hands clasped and his head angled to one side – the posture of a butler!

The intimacy achieved suited him better than, say, the impersonal space of the Festival Hall, and one of my treasured memories was the 1989 recital in memory of EMI's impresario Walter Legge at the St James's Church, Piccadilly. I think the opening Moderato of Schubert's Sonata in G, D894, lasted a full half-hour. As Bryce Morrison wrote in his review (still online: Sviatoslav Richter Blog: Novembre 2011) it had the 'capacity to sustain – against overwhelming odds – the music's argument and line… a mystical distillation of lyrical genius'.

Farcical Funeral

To get the clearest picture of the man, you need to see the Monsaingeon documentary detailed below. Made during Richter's last two years (he died of a heart attack in 1997) he talks openly to camera, the film interspersed with war-time, musical and home-life footage – Richter seemed a boisterous figure with friends around him. Most notably there's the fiasco of Stalin's funeral, Richter flown to Moscow in a plane filled with wreaths, thought to be planting a bomb when stuffing paper under a non-working piano pedal, and finally dragged off by police when crowds outside hissed his playing of a long Bach fugue.

There's also a complementary book with appendix details of everything Richter kept in or dropped from his vast repertory and a commentary on recordings he'd listened to [Notebooks And Conversations; Faber & Faber].

The Beethoven Triple Concerto he made in Berlin with Oistrakh and Rostropovich, Karajan conducting, he found 'dreadful… I disown it utterly'. And he never forgave a missing upbeat cue when they recorded the Tchaikovsky Concerto together in the Vienna Musikverein in Sep '62. 'Disgraceful pigheadedness' he declared.