Shostakovich: String Quartet No 3

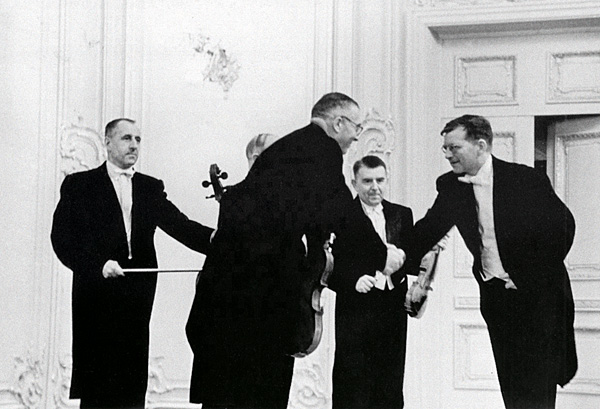

Alongside his Tenth Symphony, Shostakovich took special pride in the Third Quartet, in a way that most artists do, who have to think their latest piece is their best. More telling is the testimony of Fyodor Druzhinin, violist of the Beethoven Quartet at a much later period in the composer's life: 'Only once did I see Shostakovich visibly moved by his own music. We were rehearsing the Third Quartet… When we finished playing he sat quite still in silence like a wounded bird, tears streaming down his face. This was the only time I saw Shostakovich so open and defenceless.'

High Five

Having composed it at his summer dacha in 1946, Shostakovich dedicated the Third to the Beethoven Quartet, who went on to premiere all but the Fifteenth (and last) Quartet. Cast in five movements, enclosing two scherzos and a kind of grave passacaglia, the quartet shares several features with both the Eighth (1944) and Ninth (1945) symphonies, less laboured than the former, less bizarre than the latter. The opening Allegro is almost too perfect as an exemplar of 20th-century sonata form, and the two-chord payoff looking back to Haydn and Beethoven. The jagged opening of the second scherzo directly anticipates the more famous Scherzo of the Tenth Symphony supposedly conceived as a portrait of Stalin.

It no longer seems like historical accident that Shostakovich turned more and more towards the Quartet and away from the Symphony as genres during the course of his career. He began writing quartets in earnest as part of the sudden swerve of aesthetic direction forced upon him by official condemnation of the modernist language and amoral outlook of his Lady Macbeth opera. But the supposedly 'abstract' mode of expression and harmonious architecture of a Classical-era quartet offered a powerful outlet to a composer never short of ideas.

Shostakovich also shared with Mozart a natural fluency in transferring those ideas to the page, and a bittersweet, major-minor, happy-sad vein that comes to the fore in the finale of the Third Quartet, which begins in offbeat fashion with a long, furtive and ruminating cello solo – again, not unlike the slow introductions to the finales of several symphonies, but more ambivalent. There is a wheedling second theme that enters like a servant in Chekhov, then a foot-tapping, vodka-soaked tune, before the emotional balance is tilted by the climactic return of the passacaglia theme. Even the coda's fragmentary quotation of the movement's opening theme resists trite or straightforward interpretation. It means what you want it to mean.

Open Endings

In the course of writing this piece, I chanced to mention the Third to Carmen Flores, violist of the Villiers Quartet. For her, too, it marks the pinnacle of Shostakovich's quartet writing: 'At times, I find it just as bleak as the Eighth, especially with the viola solo at the end of the fourth movement. I have distinct memories of finishing that piece in concert, and Shostakovich messing with my emotional state of mind for days afterwards.'

The recording made by the dedicatees should be an automatic recommendation, but both available transfers are pitched around a quarter-tone sharper than any other version, including those by other Russian quartets, which seems fishy. The Borodin Quartet liked to position themselves after the composer's death as the most direct conduit of his wishes, but none of their three recordings persuade me, especially with their lumbering approach to the finale. Named after and pupils of the Borodins' cellist, the Valentin Berlinsky Quartet from Zurich (Avie) follow suit.

Among older ensembles, that leaves us with the Smetana Quartet, in atmospheric but thin sound on Praga, with microphones apparently under the noses of the leader and violist. The first fully reliable version comes from the Fitzwilliam Quartet (Decca), who played the Thirteenth for the composer in York while in their early 20s, and kept in touch thereafter. I hope it isn't chauvinism that finds me appreciative of the balance struck by several British quartets in this music, most of all the Brodskys (on both Warners and Chandos), for their commitment to the letter as well as the perceived spirit of the score.

By the side of the Fitzwilliams and Brodskys, several modern-era quartets seem determined to do things to and with the score. The Hagens' look-at-us slides (DG) soon lose their edge and their charm. The Emersons (also DG) almost breeze through the Third, especially the finale, at tempi several notches above the composer's already ambitious metronome marks (like most composers, Shostakovich heard music in his head faster than it could or should be played, the difference being he played it that way too, perhaps out of nervousness).

By contrast, the Rasumowsky Quartett (Oehms) pursue extreme fidelity but they stop several stations short of transcendence/tragedy in the finale. In search rather of imaginative truth, no ensemble is bolder than the St Lawrence Quartet (EMI/Warner, download and streaming only) led by the late Geoff Nuttall, who bends and leans into the fourth-movement passacaglia variations with the kind of total investment Peter Cropper brought to Beethoven with the Lindsays.

Rich Vibrato

Some listeners will demand Russian sound for such profoundly Russian music, and they should be happy with either the St Petersburg Quartet (Hyperion) or the Shostakovich Quartet [see below in the Essential Recordings]. Both ensembles use a string pressure and rich vibrato presently out of fashion in this music, while the first-rate modern engineering allows us to listen to them without making 'historical' allowances.

By opening the palette of vibrato to include ghostly pure tone as well as high-pressure pathos, and pushing the envelope of phrasing in the last two movements to find points of recitative-like intimacy, modern ensembles such as the Albion, Novus, Pacifica and Meta4 quartets are discovering common ground between the Third and the barer ground of its later companions. This is also true with the Classical proportions of quartet-writing in the lineage of Haydn, Schubert and Mendelssohn. It was Shostakovich's ambition to continue that lineage, not to mourn its passing.

Essential Recordings

Fitzwilliam String Quartet

Decca 4557762 (6CDs)

First issued by L'Oiseau-Lyre in 1978 and still a classic – searing in the first Scherzo, nonchalant in the finale's main melody.

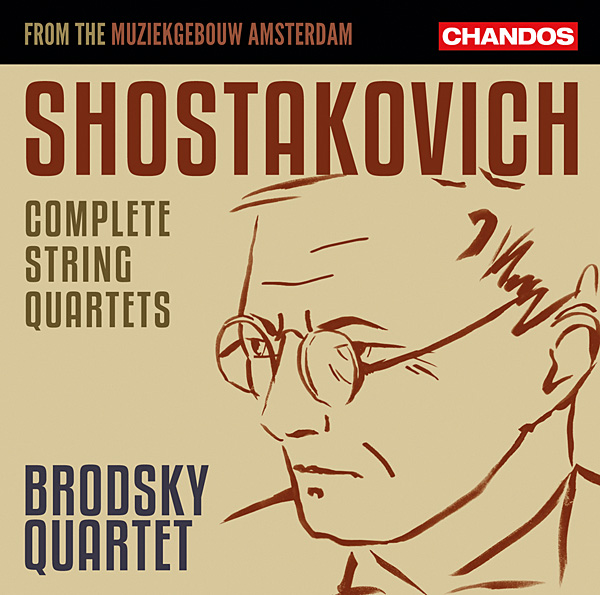

Brodsky Quartet

Chandos CHAN10917 (6CDs)

Warm, spacious Chandos sound complements the straightforward, communicative power of the Brodsky's second cycle.

Shostakovich Quartet

Alto ALC5002 (5CDs)

Claustrophobic Russian digital stereo from the mid-'90s with a high strung, authentically Soviet vibe, first issued on Olympia.

Quartetto Noûs

Brilliant Classics 96418 (2CDs)

An excellent start to a new cycle from the Italian ensemble returning to Soviet-era performing traditions: relentlessly intense.

Albion Quartet

Signum Classics SIGCD727

Brand-new both as a recording and in style, more playful in the scherzos than older versions, icier and withdrawn in the Adagio.

Novus Quartet

Aparté AP271

More legato and a richer sound than the Albions, yet no less modern as a (re)interpretation in light of Haydn and Schubert.