Saint-Saëns: Symphony No 3 'Organ'

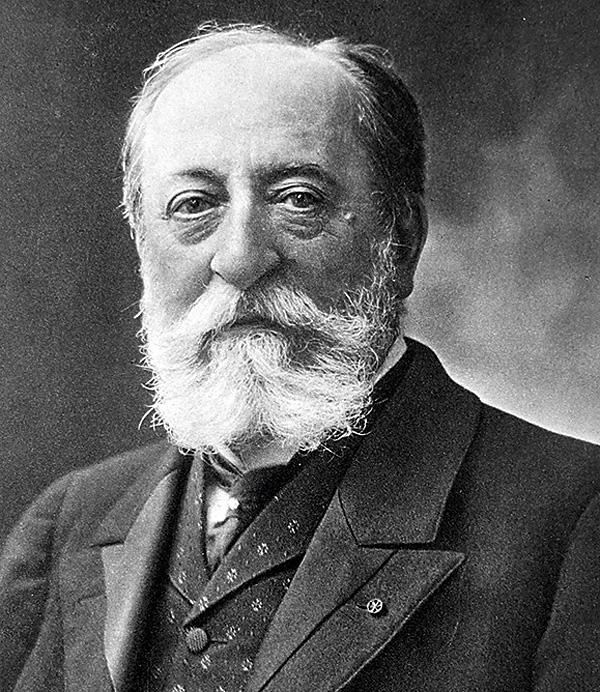

Saint-Saëns had been organist of the Madeleine Church in Paris for almost 30 years when he wrote the last of his five symphonies – the first two unnumbered – in 1886. But the commission for it came from the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and he conducted the premiere at St James's Hall in London.

'Nature is without aim', he wrote. 'She is an endless circle and leads us nowhere', which was a singularly humanistic outlook for a cradle Catholic and church organist. But then Saint-Saëns – traveller, botanist, astronomer, cartoonist – made a point of holding nothing foreign to himself over the course of a long and immensely productive lifetime.

'I am much too busy to get old', he remarked to the English organist EM Henderson at the age of 77. 'There is simply no end to my interminable career!'

Notions Of Authenticity

The kind of sound Saint-Saëns had in mind is one of several contested notions of authenticity surrounding the Third Symphony. Another is the dedication to Franz Liszt, who died shortly before its publication. The symphony's argument proceeds through the technique of developing variation, pioneered by Liszt in his piano music. All the melodies in the symphony are derived from the stepwise motif heard at the outset of the first movement's main Allegro, which itself is a variant of the Dies irae plainchant melody given a lead musical and dramatic role by Berlioz in the Symphonie Fantastique. César Franck and Vincent d'Indy looked at the 'Organ' Symphony and followed suit.

For a new kind of symphony, Saint-Saëns needed a new orchestra, which he achieved with the introduction of organ, piano and the Lisztian triangle. While he waxed hot and cold over Wagner in print, the lush harmonies of the symphony's Adagio would be unimaginable without the recent example of Parsifal's Good Friday Meadows.

But Wagner's declared antipode Mendelssohn is the model for the masterly close to the Scherzo, which weaves the leitmotif back into the texture of rippling scales and dancing winds before easing seamlessly into a sublime string-led meditation: from ballet-stage to side-chapel within a matter of bars.

Secular and sacred environments, French and German musical idioms, organ and orchestra, elements of symphony and tone-poem: all must be held in balance by performers of the Third Symphony. Responsibility for the premiere on disc fell to Piero Coppola, who also conducted the premiere recordings of Debussy's La mer and Ravel's Boléro.

Bolt-On Organs

The French HMV sound from 1930 is surprisingly full on the download-only Classical Moments remastering, the Paris Conservatoire ensemble at its tautest. There is a characteristically tight expressive screw turned by Arturo Toscanini but the lighter touch of Sir Thomas Beecham's direction (live in 1954, see Essential Recordings boxout, p155) pays dividends in the relaxed virtuosity of the RPO's playing.

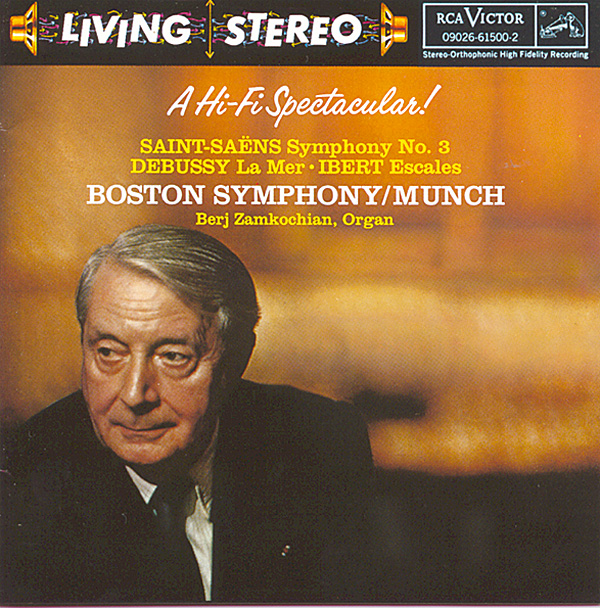

With the '60s we reach an array of excellent recordings from the US, where the 'Organ' Symphony found a second home thanks to suitably equipped concert halls, conductors with the right temperament for the piece and engineers eager to refine the kind of multi-microphone set-ups demanded by the complex orchestration.

Most strikingly hi-fi of them all is Paul Paray's Mercury recording from Detroit, crisp as a baguette straight from the oven, but (like Beecham) Charles Munch imparts a depth and radiance to the string tone within the context of a swift and hot-tempered reading that retains its classic status today.

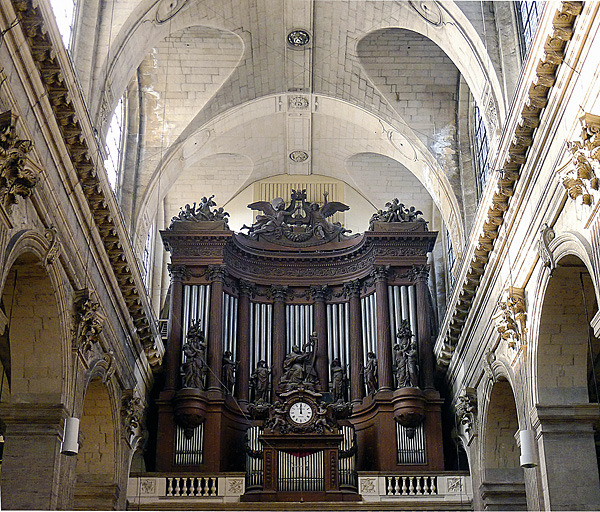

Compendious boxes take up shelf space and enjoy a limited life-span of availability but anyone in possession of the Warner set dedicated to the Belgian-born André Cluytens should investigate his gripping 1955 EMI account, with the Paris Conservatoire orchestra at the Salle de la Mutualité and the organ part taped by Henriette Puig-Roget a few days earlier on the Cavaillé-Coll instrument then sited at the Palais de Chaillot. Cluytens was a welcome guest at Bayreuth at the time, and it shows, but so does the native rapport between conductor, organist and orchestra.

Among a clutch of early digital recordings, Serge Baudo's version is rarer still, last available in a box documenting the history of EMI Eminence, well worth hunting down for the mingled grandeur and urgency of Baudo's conducting and the skilful integration of the LPO with Jane Parker-Smith's expert handling of the Cavaillé-Coll organ in the unlikely venue of Paisley Abbey.

From the same era, the flair of James Levine and Simon Preston in Berlin (DG) and Charles Dutoit and Peter Hurford in Montreal (Decca) stands up well, but don't overlook Jean Guillou and Eduardo Mata with the Dallas SO (Dorian, download only). It's a brass-heavy but nimbly played throwback to the era of Munch and Beecham. Lighter in texture but conjuring a hypnotic intensity, Peter Maag with Daniel Chorzempa and the Bern SO is another elusive early-digital favourite (once on IMP Classics).

When compared with Beecham's gas mark 9, the delicate textures and subtle phrasing of many modern recordings go hand in hand with pallid instrumental shading and low expressive temperature. Ludovic Morlot in Seattle, Kent Nagano in Montreal, Slatkin in Lyon – all are decently recorded, well-prepared, CD-available recordings using a concert-hall organ in situ but undone by a fey refinement in the face of the score's particular Wagnerisme. Monumental tempi and sticky opulence take Christoph Eschenbach's Philadelphia version too far in the other direction, while I find Yannick Nézet-Seguin in both Montreal (Atma) and London (LPO Live) straight-up vulgar.

Rush To The Head

Move away from this dominant Franco-American axis, and the refinement wrought by Jansons (BR-Klassik) and Pappano (Warner) on 'their' orchestras in Munich and Rome reaps dividends. These trenchant, extrovert live-recorded versions take an expansive, serious approach while giving the organ its head in the finale and missing only the last degree of erotic-religious passion in the Adagio.

'Bolt-on' recordings of the symphony (the nadir reached with Pierre Cochereau at Notre-Dame spatchcocked by DG onto Karajan's Berlin Philharmonic at their most glutinous) are now a thing of the past. Perhaps that's no bad thing, but no one lets rip with the piece these days, after the fashion of Munch, Cluytens, Maag or Baudo.

Two Parisian recordings come closest. The first is the unabashed Wagnerism and dynamic refinement of Myung-Whun Chung on DG, evident from the outset in the languorous phrasing of the Bastille orchestra. The second? This is the 'new authenticity' of François-Xavier Roth recorded live in the Roman Catholic church of Saint-Sulpice, with his father Daniel at the bench of Cavaillé-Coll's masterpiece.