Rachmaninoff: The Bells

Towards the end of his life, Rachmaninoff looked back in the early 1940s and regarded his recent Symphonic Dances as one of his finest works. But in the same bracket he placed his choral symphony of three decades earlier. Again, as well he might, for he borrowed and adapted the opening teaser of the early piece for the later one, as well as a good deal else such as the Dies Irae plainchant. This became a signature theme (almost an idée fixe), and an orchestral palette which continually evokes bells without resorting to the literal use of them.

Pianistic Carillons

A century and a half on from his birth on a Russian country estate, like a setting out of Chekhov, we still think of Rachmaninoff as the supreme nostalgist; the six-and-a-half-foot scowl who only smiled in his music; the tortured soul under whose fingers the piano sang of Imperial Russia's former glories.

Such images add up to much less than half the truth. As both a lifelong believer and a born musician, his head was full of the sound of bells, beyond their ritual significance –their rich harmonics, their evocation of space and distance in sound, their compass of sacred and secular, public and private worlds.

All these bells he composed into his own music, well before writing the piece that bears their name. What is the famous opening of the Second Piano Concerto other than the initially distant chime of bells? What is the early Prelude Op.3 No.2 that made his name, more than a pianistic carillon? Just as Ravel composed the movement of water, Rachmaninoff wrote music that embodied bells, both composers taking the pianistic vocabulary of Liszt and translating it into their own language.

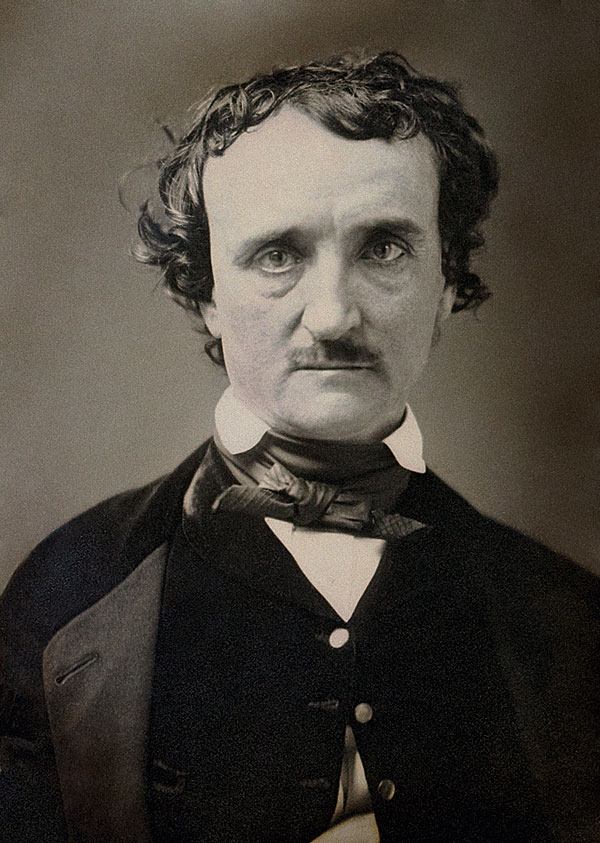

How different Rome must have been from today when, in 1907, Rachmaninoff took a holiday there, in an apartment once occupied by Tchaikovsky's brother Modest. 'Nothing helps me so much as solitude', he wrote. 'In my opinion it is only possible to compose when one is alone and there are no external disturbances to hinder the calm flow of ideas. These conditions were ideally realised in my flat on the Piazza di Spagna.' The flat was at the foot of the Spanish Steps, now the destination for every Insta-happy tourist by day, and sluiced down by Roman cleaning vans at night. One day the composer received out of the blue a Russian translation of The Bells, perhaps the last poem to be written by Edgar Allen Poe.

Who The Hell Is Edgar?

Perhaps Rachmaninoff knew no more of Poe than most listeners to Teya & Salena's Austrian entry for Eurovision 2023, but it's not hard to see how the poem would have fired his imagination. The translator Balmont viewed it as an unintended requiem for the poet himself, who had died in October 1849, aged 40, and in mysterious circumstances which could have been lifted from one of his Gothic stories. The four sections of Poe's text become progressively darker as they move from silver sleigh bells to golden wedding bells, to bronze alarm bells and finally iron funeral bells. Balmont filled his loose translation with obsessively recurrent pairs of alive yet disembodied human eyes, representing Poe as the supreme introspective visionary.

Rachmaninoff's setting combines symphonic ambition with Romance-like song writing, declamatory recitative and Mussorgskian choruses. Its overall form contrives to be recognisable, novel and entirely satisfying all at once. There's nothing quite like it, except the Sea Symphony completed by Vaughan Williams four years earlier. Both pieces sound entirely 'national' in character while setting American poetry from a cosmopolitan, international outlook.

And so, although an English back-translation of the Poe/Balmont text was made, and used by Eugene Ormandy and others, The Bells is most at home with Russian players, not only because they speak its language but because they feel its temperament, the pull towards melancholy the music initially resists, surrenders to, then transcends in a coda of dissolving quiescence unique in Rachmaninoff's output.

Though the Soviet authorities condemned the decadence of The Bells as much as the rest of Rachmaninoff's music, one of the first extant recordings was made live in Moscow in 1948. Conducted by Konstantin Simeonov, the broadcast is not so sonically compromised that the sheer character of the performance is obscured. This is even more true for the Kondrashin-conducted first studio version (both of them in a fascinating boxset of vocal Rachmaninoff on Profil).

Nevertheless, Rachmaninoff's virtuoso orchestration deserves better, and there is no shortage of first-class modern recordings (all but one of the list below made in the present century). The many moods of the piece also deserve better than Ashkenazy's diffidence and the cautiously literal hand of Dutoit (both on Decca). Kitaenko has conducted three recordings and made a meal of the Wedding Bells each time. This movement also dragged in Svetlanov's studio version, and the cor anglais melody to introduce the finale falls flat in several Western versions, such as Shaw and even Rattle.

Previn captures the orgiastic character of the third movement Scherzo, at the cost of intonation and ensemble. Rachmaninoff wrote most of The Bells in 1913 – even if he could not have heard The Rite Of Spring, given its notorious premiere in Paris that May, word of its savagery must surely have reached him. 'By the twanging/And the clanging/How the danger ebbs and flows' – as with Prokofiev and his Scythian Suite, Rachmaninoff may have wanted to show he could write Russian primitivism in his own style as well as the next man. The unbridled paganism of The Poem Of Ecstasy is there, too, in the versions led by Pletnev and Svetlanov, both master Scriabin performers.

Nails It

Jansons draws out the legacy of Rimsky-Korsakov – both in his own late operas and his orchestration of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov – in the brooding Russian-Wagner harmonies of the Wedding Bells. He also takes an unusually weighty approach to the Scherzo, but it works because he demands (and gets) such vividly pointed playing and singing.

Overall, however, I find the best of all worlds in Noseda's version. Here, the sense of occasion from a live recording is handled by the experienced Chandos team while the all-Russian singers are led by a conductor with Mariinsky greasepaint under his fingernails, as a former assistant to Gergiev. The Bells belongs to its time and place no less than Stravinsky's Rite or Schoenberg's Gurrelieder (1913 was a good year for musical premieres). Noseda and his team present The Bells alongside them.

Essential Recordings

Moscow PO/Kondrashin (1962)

Praga Digitals PRD350123

A visceral Melodiya recording – it's overlit, cavernous and authentically Russian, animated by Kondrashin's relentless baton.

Russian Nat. Orchestra/Pletnev (2000)

DG 4710292

Shiveringly evocative, with a master-pianist's natural handling of Rachmaninoff's big tunes and climactic releases.

BBCSO/Svetlanov (2002)

ICA Classics ICAC5069

Boxy Barbican sound notwithstanding, an electrifying final testament to the conductor's fiery passion for the piece.

BBCPO/Noseda (2011)

Chandos CHAN10706

Mariinsky chorus, Russian soloists and Noseda's operatic direction bring native-style opulence to a live BBC Proms recording.

Russian Federation SO/Jurowski (2013)

BelAir Classiques BAC107 (DVD)

Overflowing with affection for the piece and all its details of harmony and craftsmanship: authenticity 2.0 from an all-Russian cast.

Bavarian Radio SO/Jansons (2016)

BR Klassik 900154

A late Jansons event that recaptures all the devil-may-care intensity of his early years, plus gold-standard engineering and playing.