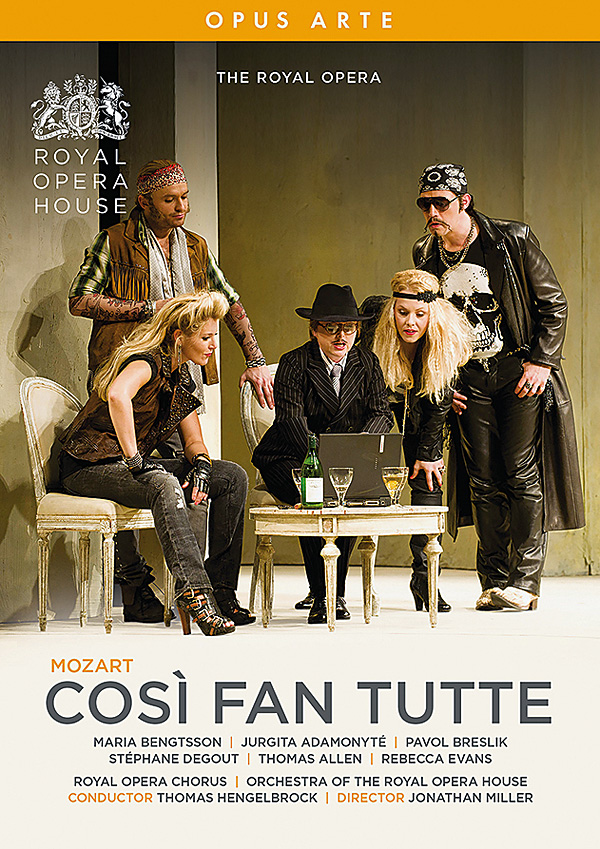

Mozart: Così fan tutte

Giochiam', says Don Alfonso, to set in motion Mozart's final collaboration with Lorenzo da Ponte: let's play a game. The nature of the game is a wager over feminine fidelity, laid with two soldiers to prove that, in the moral of the untranslatable title, 'all women are like that'.

Thus Ferrando and Guilelmo, engaged to two sisters, must each court the other's fiancée in the guise of lovelorn Albanians as a day-long social experiment, and accept the consequences of deception and betrayal in the light of the opera's subtitle, 'The School for Lovers'.

Problem Piece

In the wake of the opera's successful first run in January 1790, interrupted by Emperor Leopold II's passing which closed all the theatres in Vienna, there was no sign of the controversy which swirled around it throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th. Bourgeois audiences took exception to what they saw as da Ponte's amoral pessimism (women are all hussies) as voiced by Alfonso, and frivolous humour (but never mind).

It was Richard Strauss, above all, who restored both the fortunes of Così and its place in the repertoire with pioneering productions which honoured the piece as Mozart and da Ponte left it, rather than bowdlerising the plot for the sake of contemporary sensibility.

One German staging restored propriety by having the sisters courted by their own fiancés. Wagner thought the libretto trivial; Herbert von Karajan's telling reaction was 'Wonderful music, but in the theatre – well, I must say it is not to my taste'. As both the supreme Mozart conductor of his age, and the composer of Der Rosenkavalier, Strauss grasped what a radical and yet perfect work for the lyric theatre Così is.

The nature of the passions expressed – and initially rejected, then gradually accommodated, first by Dorabella and then her sister Fiordiligi – drew from Mozart a new language of parody homages to old lyric genres (love duet, seduction scene, oneupmanship between both men and women), pitched precisely in the same key as the libretto. Take Ferrando's 'Un aura amorosa' from Act 1: only the context and the performer can tell us that this is no ordinary suave serenade.

Before that, the opera's unstable balance between irony and sincerity is set up by 'Smanie implacabili', Dorabella's initial reaction to her fiancé's sudden call-up. The vocal and instrumental gestures place the aria in the lineage of 'woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown' scenes from Monteverdi to Donizetti, but they are too extreme, too brief and too premature to fit the bill.

Social Change

Così was not staged at the Royal Opera House in London until 1947, and only then in a touring production from Vienna. A home-grown staging had to wait until 1968. Around that time of tumultuous social change, the wider operatic public began to catch up with what audiences at Glyndebourne had known (along with Strauss) for decades: that Così is an uncomfortable masterpiece of lyric psychology.

The libretto gets under your skin, like Seinfeld or Motherland. Rather than the conventional imagery for musical masterpieces of a landscape crossed by many paths – but you can take only one at a time – Così more nearly resembles a 'sandbox'-style role-player game, in which performers (and listeners!) must make choices at every stage which affect what happens next.

Serious or send-up? Is Despina in league with Alfonso, or another innocent victim? Will the couples forgive, or forget? You decide.

Home listeners to Così in the 78 era were spoilt for choice by a single set, decades ahead of its time. This wasn't simply because of the familiarity of Glyndebourne's cast and instrumentalists with both the piece and each other. There was also the breathing tempi and phrase-making of Fritz Busch and the light-touch wit of the piano continuo and the sheer presence of the Columbia recording. This is vividly preserved on the EMI/Warner remastering of Busch's Glyndebourne legacy [9029580174] over nine CDs.

Precious few stereo recordings lived up to those standards until period-instrument directors began to revive the scale, the colours and the decorations which composer and librettist took for granted in the late 18th century. Among those rare birds is Otto Klemperer [EMI/Warner, 4043612], unevenly miked and edited but unsentimentally sensitive to the instrumental textures supporting a youthfully fiery cast, especially strong in the women led by Margaret Price's Fiordiligi.

Listeners demanding both digital sound and 'modern' instruments can comfortably settle for the Chamber Orchestra of Europe under either Georg Solti [Decca, 4783050] or Yannick Nézet-Séguin [DG, 4790641], both glamorously cast and expertly driven but neither of them as responsive to sudden or imperceptible changes of temperature (Fiordiligi's painful yielding to the 'wrong' lover, for example, in 'Fra gli amplessi') as Solti's first recording on Decca [4757033, download only].

My Così may not be yours. I'm not looking for the night in an expensive hotel put up by Barenboim, Levine and Muti. My enjoyment of characterfully sung versions by Jacobs, Currentzis and Rattle is continually interrupted by ideas from the podium, an artful pause here and a funky continuo embellishment there. Several versions by Nikolaus Harnoncourt throw out ideas, such as Don Alfonso as a Diderot-like professor of Enlightenment, as if presenting an illustrated lecture rather than a sex comedy turned serious.

Stage And Film

Great interpreters of their roles demand to be seen as well as heard, if possible. These include Christa Ludwig's Dorabella, especially when playing off Gundula Janowitz's regal Fiordiligi (go straight to YouTube for Vaclav Kaslik's Unitel film of 1968 for an old-school Così masterminded by Karl Böhm at his most pointed); Graziella Sciutti and Lucia Popp as Despina; Walter Berry, Thomas Allen and Carlos Feller as Don Alfonso.

Modern stagings tend to emphasise that, in the English title of David Freeman's 1988 Opera Factory production, 'All can be faithless'. As well as the versions listed below, I like the pace and detail of Arnold Östman in Drottningholm [L'Oiseau-Lyre 4831809] and even edgier on film [Arthaus 102005]; the emotional truth and bewildered passions of Patrice Chéreau's staging in Aix-en-Provence [Erato, 3447169].

Whether old or new, in English or Italian, any successful Così beats with the heart of tragedy as well as laughing with the soul of farce.