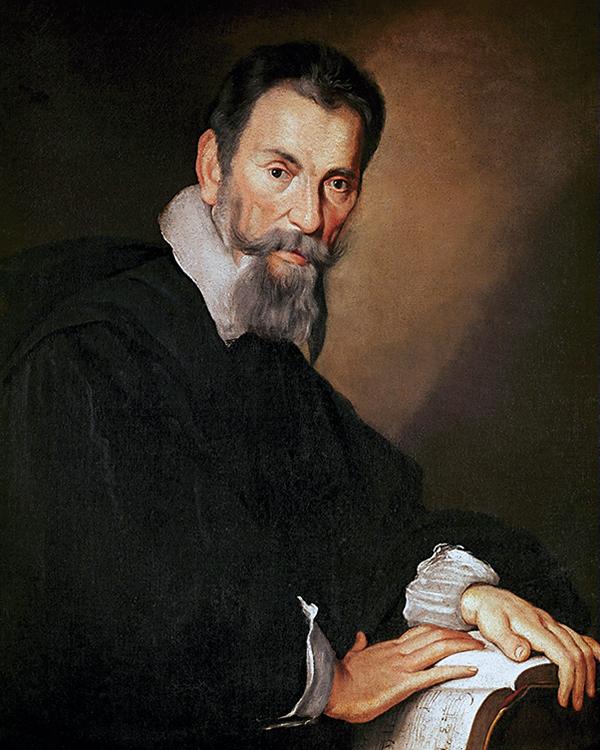

Monteverdi Vespro della Beata Vergine

Claudio Monteverdi has been labelled a Baroque composer and a Venetian composer, despite the facts that he published six collections before the 17th century even began and that he worked in Mantua until he was 45 years old. At that point, disgruntled with his terms of service, he travelled to Rome in search of new (preferably papal) employment. He took with him a newly published volume, hot off the press, of sacred works which he had written over the past decade.

Comprising a Mass setting, and the elements for an impracticably lengthy service of Vespers, the volume was dedicated to Pope Paul V and evidently designed as a lavish showcase of Monteverdi’s talents. Whether or not the Italian composer expected the full set of Vespers ever to be performed in sequence has been the subject of strenuous debate for decades. Rather, as with the B minor Mass of Bach, the Vespers has found a second life in the concert hall and recording studio, as an evening-length summation of individual genius.

How to bring the Vespers to life has proved no less contentious. There’s nothing especially ‘authentic’ about the mixed buffet of continuo instruments commonly encountered, including harpsichord, organ, theorbos, sundry varieties of string bass, you name it. In any case, balancing them out can only be achieved by sleight of hand at the mixing desk. Indeed, the only continuo instrument cited in the 1610 publication is the organ.

Space and spectacle

The history of the Vespers on record effectively begins in 1953, when Anthony Lewis recorded it for the new L’Oiseau-Lyre label with a scratch ensemble in Paris. This recording has never been reissued on CD, but streaming it on Tidal shows how astonishingly well Lewis and company hold up. The instrumentation may not be especially rich or colourful, the rhythms are a touch rigid, but the style is all there.

Lewis captures the flow between solo and concerted voices and instruments, the space and spectacle which are essential for any Vespers, live or on record, and the contrast between high solemnity and madrigalian sensuality. Only the genteel timbre of one or two solo voices, and the excellent mono sound, date the enterprise.

The pre-digital recording I return to most often, along with Lewis, was directed by Robert Craft in Los Angeles. Also released in 1967 (an exceptional year for the Vespers!), this takes a relatively minimal approach to matters such as instrumentation and decoration, but the result isn’t at all plain or puritan. Tilson Thomas played continuo, and Stravinsky attended the sessions.

Craft brings a dancing joy and sense of fun to the unaccompanied Nisi Dominus, light years expressively from any of his contemporaries. CBS producer John McClure uses both stereo and studio possibilities to telling effect in a high contrast recording of intimacy and majesty. Everyone plays and sings as though the Vespers had been written that year – not in the sense of sketching out a performance, but bringing something new and electric to life.

A new standard

Still, the first recording to engage fully with scholarly debates regarding the form, purpose and pitch of the Vespers was made by Andrew Parrott and his Taverner Consort. This 1984 version is a radical attempt to reconstruct a festal context for these pieces, so that they hang together as more than a sequence of Monteverdi’s greatest hits. And, paradoxically, weaving in plainsong as well as instrumental interludes by Cima enhances the experience of the Vespers as a monumental whole.

Finally – or 30 years on from Lewis, anyway – it becomes possible to hear an elegant play of both madrigalian harmony and intricate counterpoint in the Laudate Pueri. Voices and instruments are both purer-toned and better tuned, filling a liturgical space with relaxed confidence rather than hectic intensity. In pitching the closing Magnificat down a fourth, in the one-per-part scoring and the gentle, tripping articulation of early-music stars such as Emma Kirkby and Nigel Rogers, Parrott’s version both set a new standard as well as the template for many successors.

Bringing it home

It would take two more decades before early-music culture had embedded itself sufficiently in Italy to produce a native, historically informed recording. With his experience of performing and recording the madrigals, Rinaldo Alessandrini [Naïve] goes all out in re-imagining the Vespers for the recording studio, as an essentially intimate experience. Additionally, recent versions led by Italian colleagues Federico Bardazzi [Brilliant] and Gabriel Garrido [K617] are unaffectedly stylish in ways hard to imagine even 30 years ago.

Nevertheless, if there is one person synonymous with the Vespers over the last 60 years, it must be Sir John Eliot Gardiner, who founded his Monteverdi Choir to perform the work as a 20-year-old undergraduate. His recordings in 1974, 1989 and 2014 almost chart the performing history of the piece by themselves in that time. Moreover, all are staged with an acutely responsive ear and eye to the ambition of the work as a total synthesis of 17th century styles, placed at the service of God.

Essential Recordings

Columbia Baroque Ensemble/Craft

Sony 19658706112 (44CD)

Impractical if all you want is the Vespers, but full of treasures from Gesualdo to Webern, with the Monteverdi a highlight.

Taverner Consort/Parrott

Virgin/Warner Classics 5616622 (2CD)

Early digital era, but surprisingly wide dynamic range for the time and sensitive use of space in a modern classic version.

Monteverdi Choir/Gardiner

DG Archiv 4295652 (2CD)

The second of Gardiner’s three versions, slightly ‘English’ despite its Venetian setting, includes an alternative closing Magnificat.

La Capella Reial/Jordi Savall

Alia Vox AVSA9855 (2CD)

Warmer, more enveloping sound, with Savall embracing both the theatricality of Gardiner and the gentle, relaxed vibe of Parrott.

La Compagnia del Madrigale/Maletto

Glossa GCD922807 (2CD)

The most stylishly up-to-date and polished of Italian versions, underpinned by a richly textured battalion of period brass.

Pygmalion/Pichon

Harmonia Mundi HMM93271011 (2CD)

Recorded after a son-et-lumière tour of the piece around France: a sonic and musical spectacular, surely as Monteverdi intended.