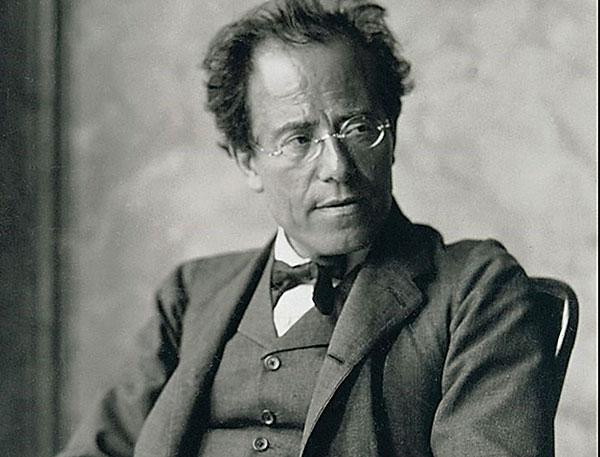

Mahler: Symphony No 5

There are some wilfully odd things said about the Fifth even by its interpreters. Mehta called it Mahler's Eroica (why? Because it has a funeral march and a happy ending?). Much emphasis is placed on its 'purity' of discourse as though this would make it a better or nobler symphonic statement. According to Bruno Walter, 'nothing in my talks [with Mahler], not a single note of the work, suggests that any intrinsic [extrinsic?] thought or emotion entered into its composition'.

No-One Died

Yeah, right. Mahler himself once remarked that from Beethoven onwards, 'There is no modern music that has not its own inner programme', and he was the most autobiographical of composers. It is surely this aspect of his work, and of his symphonies as 'music for conductors', rich in potential for varied and even contradictory interpretation, that stimulated a Mahler revival in the postwar years. This was fuelled further by innovations in recording technology that would later do these large and complex scores justice on record.

As for the Fifth, it seems now that Mahler sent the Adagietto to his future wife Alma as a gift during their whirlwind courtship in the winter of 1901. The score of the symphony is dedicated to her, like the Eighth, though he continued to fiddle with the orchestration until his death. The fixed form in which we hear it today is the work of later editors.

Simon Rattle sought to correct a misapprehension about the Adagietto – 'No one died' – which arose after Bernstein conducted it at the funeral of John F Kennedy, and then through an increasingly elegiac performing tradition. Mahler pioneers such as Walter, Kondrashin and Rosbaud had needed no telling to phrase it as a love letter, halting but ardent like Mahler himself. Through this eight-minute piece, significant out of all proportion to its scale, we can see what he saw in her – the Schindler girl, the darling of Vienna's salons. It will not serve as a 'slow movement' for the symphony.

One of the oddest features of this subtly odd symphony is that its first movement is its most likely candidate for a slow movement in the traditional sense. To hear this, you must put out of mind all the dazzling and arresting performances of the opening short-short-short-long fanfare, with its hidden-in-plain-sight hat-tip to the Fifth of all Fifths, Beethoven's. Given full value, played with Mahler's specific demands in mind, the notes of the trumpet fanfare presage a grim death march.

Just A Minute

Look at the Fifths on your shelf. If there's a three-minute difference between the first and second movements (and there often is), it's time for an upgrade. In Walter and Harding, late Bernstein and Tennstedt, the difference is a minute or even less. In the case of the first movement, the mood of the funeral march is less a manifestation of tempo than a trenchant rhythm with dark colouring, heavy phrasing and an emphasis on the stalking bass line. 'Like a cortege', Mahler had instructed, and Bruno Walter gives us a raggle-taggle bunch of mourners, Rembrandt-coloured in their obstreperous humanity, like a cousin to the first Nachtmusik movement of his Seventh Symphony.

Played and heard in this way, the march also returns to the opening arguments of the Second and Third, as a rite of death and a march of life respectively. Then the savagery of the second movement emerges with maximal contrast. The peculiar form of the Fifth begins to take shape as yet another attempt by Mahler to remodel Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique for himself, with the Adagietto as upbeat to the finale instead of a march to the scaffold.

Adrenaline Rush

In both the Fifth and the Fantastique, a loose centre of gravity is held by the bucolic evocations at their heart. For all their textural sophistications in the Scherzo, Bernstein, Harding and Tennstedt leave the mud on Mahler's boots. This is no place for the concerto-for-orchestra brilliance of Dudamel, Maazel and Solti. Nor is it really a piece for cautious and selective engagers with Mahler – the likes of Barenboim and Karajan, let alone the kind of generic appassionato generated by Gergiev. Klemperer never touched the Fifth. Hermann Scherchen liked doing it, but only in a version of his own devising that didn't so much spatchcock the Scherzo as slice and dice it into a five-minute nugget.

Perhaps the trickiest movement of all is the finale. This is not only in technical terms – holding together the continual changes of tempo – but in sustaining the momentum through the pages of busy counterpoint that eventually earn the overwhelming adrenaline rush of its closure. (Perhaps Mahler was striving at this point to emulate another glorious Fifth: Bruckner's.) This is where Barbirolli's vaunted EMI recording dies on its feet. Rattle works hard, too hard, to make every phrase interesting, but I wonder if his heart is in it. As I do with Boulez and Haitink, who gave the Fifth in concert much less often than they did the other symphonies.

In their different ways, all six of the Essential Recordings [see boxout below] hold on to the exhilarating release of the finale. Most take an attitude of super-sized Haydn to the rustic truculence and urban academicism which brings Mahler 5 into a canonic line of Austro-German symphonies, from Haydn 104 to Schubert 9 and onwards.

Soft Spot

Each is also imprinted with the stamp of their leader, which is as it should be in this 'conductor's music'. There's a tightrope intensity to Abbado that feels definitive while listening. But then so does the ferociously sinewy Bernstein, and so on. Don't imagine the Harding operates at a lower temperature; as with Abbado, a forensic ear for detail doesn't preclude living in the moment, and the playing of the SRSO is phenomenally committed.

Among overlooked also-rans, I have a soft spot for Zinman in Zürich (RCA – much warmer than his Beethoven), Macal in Prague (Exton – because Czech Mahler has a special, rounded character all its own), and Otaka in Tokyo (Camerata). The last is a sentimental choice because I first heard the symphony when Otaka did it at the BBC Proms in 1988. The place erupted and the late Peter Barker intoned on Radio 3, 'Mahler's Fifth Symphony: a journey from darkness to light'. Which said all that needed saying.

Essential Recordings

New York Philharmonic Orch./Walter

Naxos 8110896 (released 1947)

The first studio recording of the Fifth, in boxy mono, sometimes tentative and plain in execution but true to the spirit of the piece.

Moscow Philharmonic Orch./Kondrashin

Melodiya MELCD1002475 (7CD) (released 1974)

Perenially under-rated, Kondrashin secures phenomenally secure playing at speed, and the Soviet stereo is perfectly decent.

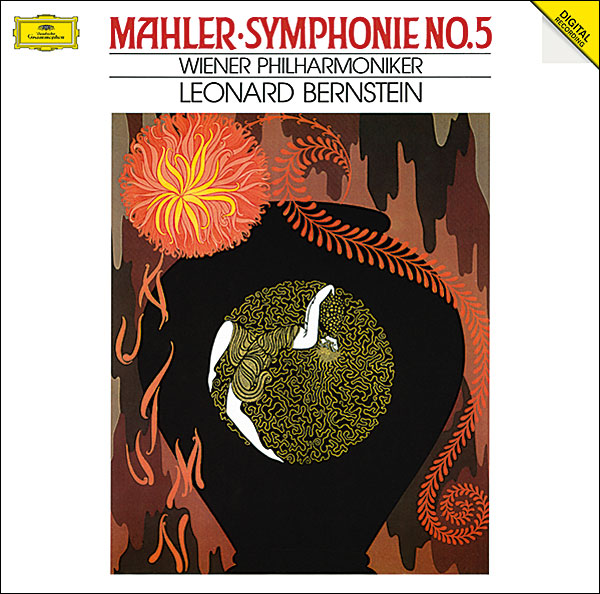

Wiener Philharmoniker/Bernstein

DG 4776334 (released 1987)

The drawback here is the distant sound, live in Frankfurt. Go to YouTube and you'll find a mind-blowing BBC Prom from the same tour.

150th Anniversary - Mahler Complete Works

EMI/Warner 6089852 (16CD) (released 1988)

More live and sub-par sound, from the RFH: one of those baggy, thrilling and quintessential late Tennstedt events.

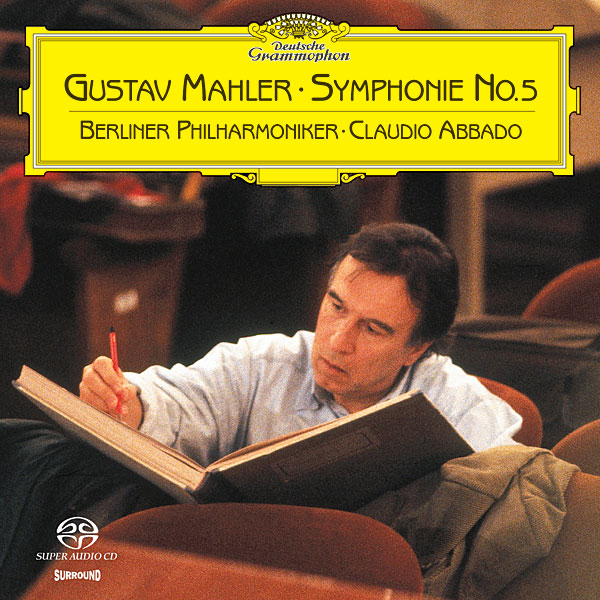

Berliner Philharmoniker/Claudio Abbado

DG 4864061 (LP) 4377892 (CD) (released 1993)

Still a recessed live sound, but a recording near perfect at squaring the circle of the symphony's many awkward paradoxes.

Swedish Radio SO/Daniel Harding

HM HMM902366 (released 2016)

Studio conditions but 'live' feel and superbly vivid sound that complements the detail of a slow-burn interpretation.