Joseph Martin Kraus The Swedish Mozart

The title is neither original, nor strictly accurate. Born five months after Mozart in June 1756, Kraus grew up in the German town of Buchen im Odenwald. His father was a clerk who (not unreasonably) regarded music as an unstable profession and pressed his son into a law degree. The plan failed, and by the age of 20 Kraus had composed pieces for the church including a Te Deum, a Requiem and a Passion oratorio [see Essential Recordings, opposite].

Troubled Souls

Kraus was no prodigy, but he had a voice of his own from early on. Not only did the young composer write his own text for Der Tod Jesu, he set it to music with an individual ear for harmony (tending towards dark and haunted minor tonalities) and instrumentation which paints story and text with graphic naturalism. He continued to master this voice for the next quarter-century, before dying from tuberculosis in December 1792, a year after Mozart.

Try out the Cantata he composed some months earlier for the funeral of the assassinated King Gustav III (a work that effectively became his own Requiem, in another uncanny parallel to Mozart). Perhaps you will think, as I did when I first heard the piece on a live EBU broadcast in 1991, where has this music been? Why aren’t there 20 rather than two recordings? Is there anything else like it?

What Kraus refines for himself is the Don Giovanni and Idomeneo side to Mozart, otherwise known as the Sturm und Drang style of late-18th-century Classicism, associated most of all with CPE Bach and with Haydn’s mid-period symphonies. Time and again Kraus’s music seems to speak beyond its time of troubled and restless souls.

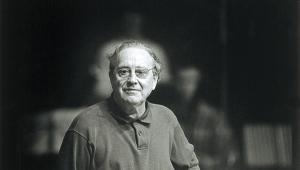

Werner Ehrhardt: a champion for Kraus on Capriccio and Deutsche Harmonia Mundi

Shadow Play

For him to do this in memorial music is understandable. Try almost any of the symphonies, and you will hear once more a composer writing shadows and frowns and whispers into a genre associated at the time less with furrowed thoughts than popular entertainment.

This kind of defiant soul-bearing brought Kraus respect but not much reward during his life. Before he abandoned his law studies, Kraus made friends with a Swedish fellow student, who persuaded him to apply for a musician’s post at the court of Gustav III in Stockholm. Arriving in the Swedish capital in 1778 at the age of 21, Kraus soon found work but not enough money. Writing back to his anxious parents, he called himself a ‘living mortgage’.

Severe Beauty

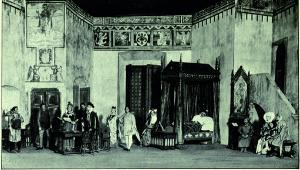

The breakthrough came three hard years later, with his opera Proserpin. This ancient-Greek abduction myth was adapted by the king himself, with the Swedish-language libretto (a rarity in those days) written by a court poet. Idomeneo premiered in Munich the same year, and the two operas share a severe beauty, though it would be idle to pretend that Kraus matches Mozart’s depth of psychological characterisation.

Proserpin stands alone among Kraus’s operas to have received a complete recording, long-deleted though available on streaming platforms, and sung by a strong native cast. Meanwhile Soliman II (1788) awaits a revival in modern times – the splendid alla turca Overture appears on the album of overtures on CPO, conducted by Claudio Astronio.

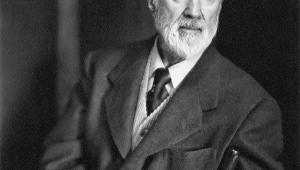

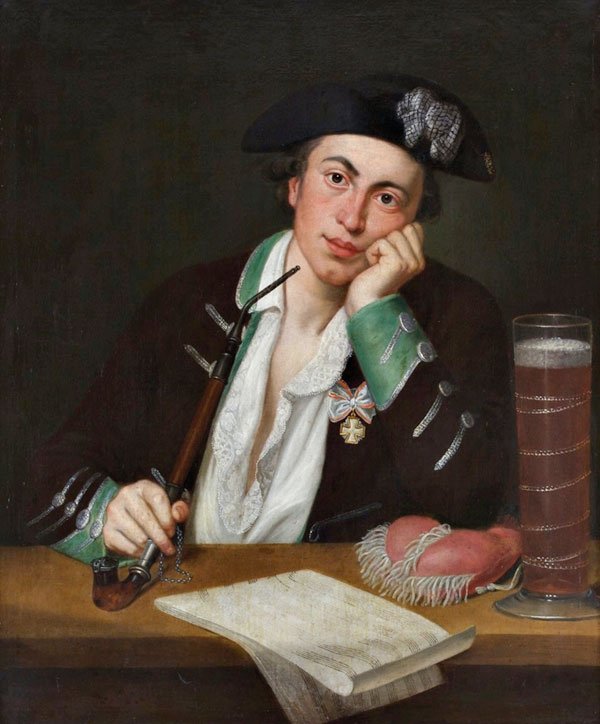

A 1775 painting of Kraus by Jacob Samuel Beck (1715-1778)

Aeneas i Karthago, his epic setting of Virgil composed 70 years before Berlioz produced Les Troyens. Goodness knows if the six-and-a-half-hour original (!) will ever surface, but a 2011 performance on German radio, at half that length, presents a score worthy of its subject, full of nobility, grandeur, Rameau-accented ballets and orchestral touches.

Gluck is the missing link here, between Kraus and the familiar Classical masters, and Orfeo ed Euridice was performed more often in Stockholm than in Paris or Vienna. From the opening bars of the C minor Symphony, dedicated to Haydn, it’s clear that Kraus also knew Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide, cast in the same vein of high-flown tragedy. Haydn himself remarked that the symphony ‘will be regarded as a masterpiece for centuries to come... there are few people who can compose something like that’.

Theatre Music

Kraus wrote the symphony in Vienna, during a five-year Grand Tour, having become a court composer and trusted aide to King Gustav. In Vienna, he joined the same Masonic Lodge as Mozart. Returning to Stockholm in 1787, he produced more theatre music including Fiskarena (The Fishermen), a colourful ballet of hornpipes and pastoral interludes. Naxos has issued this complete, along with a good deal else of Kraus’s surviving output, such as rough-and-ready accounts of the violin sonatas.

Gustav III of Sweden, mourned by Kraus in the Funeral Cantata

The symphonies fare better on Naxos, and their Kraus albums gain value from the booklet notes by the leading modern authority on Kraus, Bertil van Boer. You need to look elsewhere, however, for the Funeral Cantata, which is coupled on DHM with the Trauersinfonie written by Kraus for the King’s funeral.

Opening with the drum beats of the procession as it moved into Riddarholmen Church, this symphony matches Purcell’s Funeral Music for Queen Mary and Haydn’s Trauersinfonie (No.44) for simple and solemn pathos, ending in chords which uncannily echo Mozart’s Masonic Funeral Music (there is no evidence Kraus could have known it).

Sweet Emotion

The king’s death put paid to a prospective staging of Aeneas i Karthago, and Kraus died months later. Even his finest music cannot be claimed to share the kind of long-term vision and development that would elevate Haydn and Mozart above their contemporaries. What he could do like few others beyond them, however, was paint an emotion in sound. Could he exalt and delight? Possibly not, though his chamber music is the place to find a sharp ear turned to elegant convention. The D major Piano Trio and Flute Quintet both unfurl one happy melody after another.

Once more like Mozart, Kraus seems most often to have worked quickly and directly from his thoughts. Take the Stella coeli, an unusual piece of late-ish sacred music, from 1783, which he wrote directly into manuscript without sketches, including a four-part fugue (this takes some doing).

The series of recordings on both Naxos and led by Werner Ehrhardt elsewhere should by rights lead to exploration of scores both unheard and presumed lost. Whether considered Swedish or German, a secondhand Mozart or simply himself, Kraus is worth your time.

Essential Recordings

Theresia/Claudio Astronio

CPO 555 5792

Punchy, sleek and hi-def accounts of the overtures for opera and ballet. The best place for newcomers to catch the Kraus bug.

Concerto Köln/Werner Ehrhardt, etc

Capriccio C7325 (5CDs)

Good-value round-up of cantatas, symphonies and theatre music. Not quite all the Kraus you’ll ever need, but a fine start.

L’Arte del Mondo/Werner Ehrhardt

DHM 294025631626

The funeral music for Gustav III, cantata and symphony. Kraus at his most intense, in vivid period-instrument performances.

Tapiola Sinfonietta/David Aaron Carpenter

Ondine ODE1193-2

A pair of edgy viola concertos, plus a more expansive Double Concerto for viola and cello: Kraus the Romantic before his time.

Jaap Schröder, Kari Ottesen, Lucia Negro

The best single-disc survey of Kraus’s chamber music, where he suppresses his dark side and writes purely for enjoyment.

Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra/Helmut Wolf

Carus CAR83321

Der Tod Jesu, Kraus’s early but characteristic Passion oratorio, recounting the Crucifixion of Jesus with theatrical word-painting.