Iannis Xenakis: Greek Revolutionary

It would be pleasing though wrong to contend that Xenakis's time has come, a century after his birth. For one thing, the Greek composer and his achievements were celebrated across the world during his own lifetime. Like Beethoven and Stravinsky before him, he enjoyed as many successes as scandals. For another, the stiff wind of modernism which blew through European culture during the first half of the last century has slackened off to a climate of gentle zephyrs.

Music Industry

Rather, we need this music to remind us of a time when music really mattered, not as therapeutic balm but as a vital call to action and new thought. In any case, it was not written in the hope of a future, more receptive audience. Again like late Beethoven, it will always challenge us here and now. From the lonely piping of an ancient Greek aulos (and Debussy's Syrinx) to the thrash of Japanese noise merchants such as Merzbow, the output of Iannis Xenakis not only embodies but embraces all the possibilities of making sound into music.

Industrial and architectural metaphors come readily to mind when discussing his music. It often wakes up with an alarm call, it flows like molten steel rather than water, it spreads like the grid of a fast-growing city and it ends either in exhaustion or with the abrupt certainty of a car coming off the assembly line, ready to go somewhere else. There is room for reflection but not leisure.

Xenakis did not care for bar-lines – chopping up notes and phrases into discrete and ready-packaged units of sense – or for the idea of music as a language, or for many other widely accepted norms of communication, musical and otherwise. Instead, he shared with his teacher Edgard Varèse a conviction that listeners deserve to be shocked into submission (carried to extremes in Terretektorh, which places the musicians among the audience). Attempting to squint at a Xenakis piece through a narrative lens is likely to lead to a series of baffling dead ends.

As a pioneer of computer music, Xenakis took Schoenberg's principles of serial organisation several stages further, almost (never quite) to the point where the composer-derived algorithms could 'write' the piece. He understood that computers do not 'think' in terms of stories, but in code; musical notation is peculiarly well adapted to follow suit (much more so than words). Several of his 'ST/' works advertise their mathematical construction on the tin, named after the stochastic method of their composition and then the number of required performers (ST/4, ST/48 and so on).

The Outsider

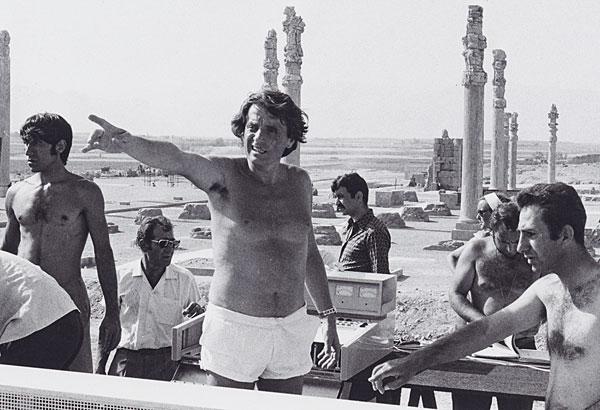

Even past these dauntingly dry titles, the progress of his music is short, messy and eventful, like life – not least his own. As a fighter in the Greek Resistance he almost died from shrapnel wounds which left him blind in one eye and with a physiognomy mirrored uncannily by the craggy contours of later orchestral pieces such as Pithoprakta and Achorripsis. Electroacoustic epics such as Persepolis and La Légende d'Eer stand out as lonely peaks beside the controlled explosions of Jonchaies and other 15-minute earthquakes in sound.

These exotic titles point us towards the essential Greekness of Xenakis's music. As Messiaen remarked when he shrewdly turned down Xenakis's request for composition lessons, 'No, you are almost 30, you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music'. Off Xenakis went, working with Pierre Schaeffer's musique concrète colleagues, eventually securing commissions worldwide, remaining ultimately an outsider, almost uniquely gifted with the ability and the drive to bridge the 20th-century's ever widening chasm between CP Snow's 'two cultures' of science and art.

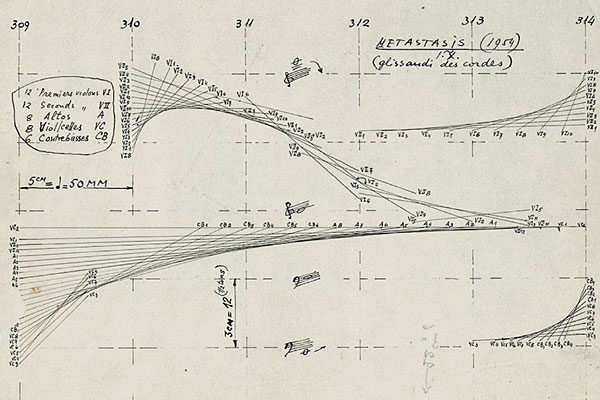

If anything, the most significant mentor in the composer's life was the architect Le Corbusier, whose studio Xenakis joined after the war. His brief but dazzling career as an architect ended on a high with the swooping lines of the Philips Pavilion designed for the 1958 World Fair in Brussels, overlapping with his life as a composer. This began in earnest in 1955 with the premiere of Metastaseis at Donaueschingen, one of the German temples of new music. It almost caused a riot to rival the 1913 premiere of The Rite Of Spring, though its most individual element is not the bump-and-grind of the main action, resembling later scores of Varèse such as Déserts, but the queasy opening glissandos which became a Xenakis trademark, signifying some huge, unstoppable, unquantifiable force.

Vinyl Fans

The notorious Metastaseis premiere was led by Hans Rosbaud, an underrated but inspirational interpreter of everything from Mozart to Tchaikovsky to Xenakis, whose recorded legacy is being belatedly catalogued by comprehensive boxes from SWR Music. Between them, the US-based mode records and Belgian Timpani label have covered most of Xenakis's output in modern recordings that are not only well prepared but carefully engineered (not all presently available on CD). Meanwhile, vinyl fans should check out Karl Records online. This Berlin-based label has recently issued the complete electroacoustic works of Xenakis in a luxury 5LP (and CD) box set, with the individual albums due for separate release.

Giant Star

In its newly remastered form, Bohor (1962) is still an astonishing demonstration of the potential for world-building in the electroacoustic realm, an immersive masterpiece to compare with Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge and Cage's Fontana Mix. Alongside Metastaseis and Jonchaies, however, I urge you to try Kottos as an entry point for Xenakis.

Kottos not only challenges a solo cellist to live up to the multi-limbed giant of its title but responds to individual interpretation every bit as much as late Beethoven: compare and contrast the take-no-prisoners approach of Rohan de Saram (in the Montaigne collection – see 'Essential Recordings' boxout below) with the more impressionistic portrait built up by Arne Deforce (on Aeon).

The cello had been the composer's own instrument in his youth, and there is the feeling of a self-portrait about the work's gritty surfaces, unpredictable leaps of thought, pride and overcoming of adversity – take it or leave it.

Essential Recordings

A l'île de Gorée, Jalons, Phlegra, Thallein

Apex/Warner Classics 2564642022 (two discs)

The neoclassical Xenakis: Boulez directing ensemble pieces such as a stunning concerto grosso with harpsichord.

Ata, Jonchaies, Metastaseis, etc

Col Legno WWE1CD20504

Pioneering German radio accounts of sonic orchestral juggernauts such as Jonchaies and the Mahlerian sweep of Ata.

Antikhthon, Keqrops, Synaphaï, etc

Decca 4785430

Contrasting piano concertos: the volcanic Keqrops and the rapid lava flow of Synaphaï, plus an elemental ballet for Balanchine.

Evryali, Kottos, Tetras, etc

Montaigne MO782137 (2 discs)

An indispensable piano and chamber collection features the scorching Tetras for quartet and jazzy piano writing of Evryali.

Pleïades, Rébonds A & B

Linn CKD495

A multi-tracked version of an astonishing percussion tour-de-force (Pleïades) plus a funky modern rite for solo drummer.

A Colone, Medea, Nuits, etc

Hyperion CDA66980

A superbly sung choral collection, bringing together Xenakis at his most primordial (Nuits) and incantatory (Serment).