Gustav Mahler: Symphony No 4

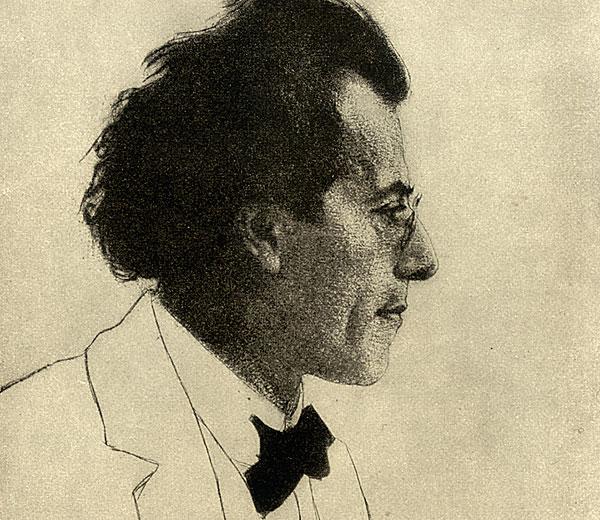

As this issue of HFN is likely to reach you during the festive period, why not a piece that starts with sleigh-bells? No, not Leroy Anderson, but Mahler's fourth symphony, written in 1899-1900, and first performed in Munich in November 1901. The UK premiere came just a few years later in a 1905 Prom concert with Sir Henry Wood.

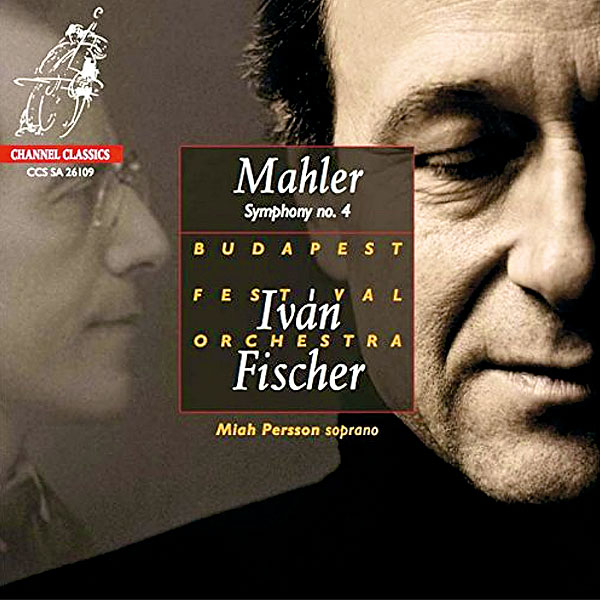

As the conductor Iván Fischer has said, Mahler had set out to create 'a childish symphony' the opening two-flute motifs 'like two children in a kindergarten'. But the music flows with a complete naturalness, says Fischer, combining Viennese flavours with innocence to achieve something entirely unique.

The climax of the slow movement – a set of variations – sounds like the gates of heaven opening, and it leads to a vocal finale: a song depicting the 'Heavenly Life' of the saints. Apparently Mahler intended to add a bitter contrasting section 'Das Irdische [Earthly] Leben' but changed his mind – just as he first thought of including the song here as part of Symphony No 3. As it is, that work from 1896 is by far his longest – at around 95 to 100m.

Gustav Mahler's 'first period' works – starting with the story of fratricide, a wedding and a singing bone, Das Klagende Lied, begun in 1878 – were stimulated by a collection of German folk poetry, Des Knaben Wunderhorn, including the setting here. Mahler had composed music for his finale, changing the title, as an earlier standalone piece.

The Symphony's scherzo has a pictorial basis, after Mahler saw a self-portrait by Böcklin showing 'Freund Hein' [Friend Henry], the skeletal figure of death, with his fiddle. The orchestral leader tunes his violin up by a whole tone here. Böcklin canvases also influenced the 'St Anthony and the Fishes' settings in Mahler's 'Resurrection' Symphony and Wunderhorn songs, and Rachmaninov's Isle Of The Dead and his Prelude for piano, Op.10:3.

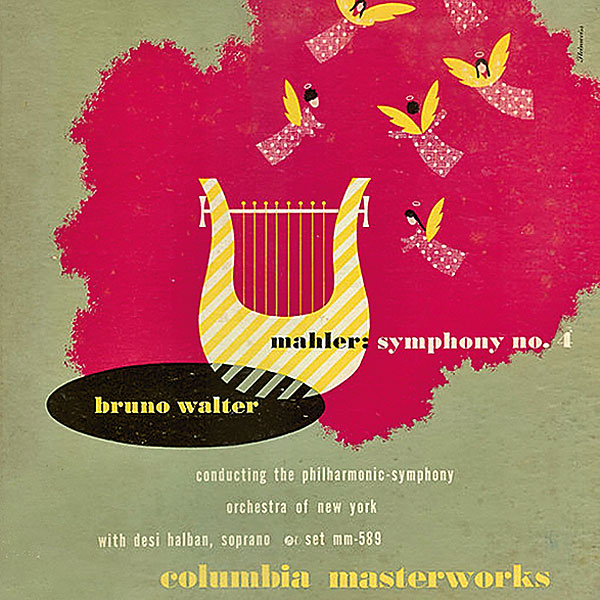

Symphony No 4 is arguably the best starting point for someone new to Mahler – either this or the song-cycle Kindertotenlieder – and for older readers it will have been the recording made by Mahler's assistant in Vienna, Bruno Walter [Classical Companion HFN Mar '17], that they are sure to have first encountered.

Japan First

It came out on 78s in the States in 1948 and was a very early LP. In this country the HMV 78s were followed by a Columbia LP transfer, then it was reissued in Philips' cheap label NBL series, later reverting to CBS/Sony on LP and CD [88691920102]. But as the 1950 Record Guide said, 'the choice of Desi Halban as singer is regrettable. She is heavy in timbre and clumsy in phrasing'. Halban was an Austrian emigree who arrived in NY in 1940; she suggested to biographer Henry-Louis de la Grange that some tempi in that recording may have been compromised to fit onto 4m sides. However, we have live recordings to compare, with Walter and the VPO, with soloists Elisabeth Schwarzkopf or Irmgard Seefried.

Surprisingly, the very first electrical recording came, not from Amsterdam (where its principal conductor Willem Mengelberg introduced Mahler to Concertgebouw audiences and where Mahler had directed the Dutch premiere) but from Tokyo in May 1930. Mengelberg's 1939 recording – which I remember as pretty eccentric – was reissued on a Philips CD but is now available as a Pristine Audio download at €11.

Otto Klemperer had also worked with Mahler, and had directed the off-stage band at the 1895 premiere of the 'Resurrection Symphony' and then made a two-piano reduction. Hearing it, Mahler wrote a testimonial which opened the door to Klemperer's conducting career. He only recorded four of the nine Symphonies [see 'Essential Recordings'] and his Philharmonia studio recording of No 4 with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was made in April 1961 – there are various mono alternatives from radio sources, two of which are on YouTube.

EMI's earlier Philharmonia stereo recording was by the Polish conductor Paul Kletzki – he did the first version of Das Lied von der Erde with two male soloists, well before the Bernstein/Decca LP. The two works were on a Warner 2CD set [4769122, now download only] and both readings still have plenty to offer. (Alas, his two versions of No 1 have cuts in the finale…)

In 1961 Georg Solti made No 4 his first Mahler recording for Decca. This was with the Concertgebouw as a replacement for its van Beinum mono LP of the symphony (1952); by chance I listened to it quite recently and didn't find it that convincing. He was far better later in his LSO No 1.

Van Beinum's Amsterdam successor, Bernard Haitink, made seven recordings in Amsterdam or Berlin – in 1967, '82 [DVD & Blu-ray], '83, '91 [DVD], '92, 2005 and 2006. The readings did not change much and might be chosen on the basis of the singer: Elly Ameling in the first version, Christine Schäfer in the last. I wonder if his 90th birthday concert performance last May, with the LSO and soprano Sally Matthews, will appear on the orchestra's own label at some time.

I also liked Daniele Gatti's version with the Concertgebouw [HFN download choice Sep '18] of which I wrote: 'if you think this is a "comfortable" work this will all be a revelation. Gatti brings out all of Mahler's contradictions' [RCO Live RCO18004; SACD].

Scaled Down

Collecting different recordings of Mahler 4 has inevitably led to disappointments, notwithstanding recommendations by other writers – the VPO/Abbado, BPO/Karajan (all of his Mahler for that matter), Chicago SO/Reiner, Pittsburgh SO/Previn, VPO/Maazel, Israel PO/Zubin Mehta. Bernstein's DG remake featured a boy singer and it sounds awful.

On the other hand, the LPO/Horenstein CfP LP and Swarowsky on Supraphon – he tutored Abbado in Vienna – stick in my mind. But when Iván Fischer's SACD came along that really made me sit up. It's a highly individual reading of the work, as with later instalments in his Budapest Mahler cycle, not all of which are so convincing (Nos 5 or 7), and has an ideal vocalist in Swedish soprano Miah Persson.

Trevor Pinnock's chamber version by Erwin Stein [detailed below] makes a stimulating follow-up to 'the real thing' and it's very well done by Royal Academy students.

There are complete discographies worth browsing at the Mahler Foundation Archive website, Symphony No 4 running to no fewer than 218 listings on my count!