Emerson String Quartet: Farewell tribute

In October 2023 the Emerson Quartet will take to the stage of Alice Tully Hall in New York. They will fiddle with the music on their stands, as they do. Their eyes will meet, their heads will lift a fraction and they will lay bow to string together for the very last time.

The Emersons have already begun a farewell tour of favourite venues with a setlist of their greatest hits. Catch them if you can. With their retirement (as an ensemble), there passes an embodiment and a guarantor of excellence that for many has made them the Berlin Philharmonic of string quartets over the last three decades and more.

Thrills 'N' Spills

Does that sound bloodless? (Does the Berlin Philharmonic?) Reading between the lines of critical reception both hot and cold, terms such as precision and accuracy and even efficiency recur often enough to imply that the ESQ, for all its virtues, was not an ensemble to get the pulse racing. In my own experience, however, on their many (sold-out) visits to London, the ESQ have delivered no shortage of thrills – and a few spills along the way.

I recall a 'Razumovsky' No 1 where the players seemed only to have met just before coming on stage. Within one of their Bartók marathons, playing all six quartets in one evening, the Scherzo of the Second almost came off the rails. Bloodless perfection? Hardly. To my mind, at least, such vulnerabilities served only to reinforce the sheer ferocious unanimity of purpose which was this quartet's modus operandi. In concert, at any rate, their late Beethoven brooked no opposition. Everything worked – almost too well. If you had questions, you wanted to ring up the composer afterwards and find out what he had been thinking (or drinking).

When they began playing in a quartet together in 1970, violinists Eugene Drucker and Philip Setzer were second-year students at the Juilliard School. Both their fathers had played second violin in distinguished quartets, Drucker's in the legendary Busch Quartet, Setzer's in the Sinfonia Quartet made up of Cleveland Orchestra players. At Juilliard they were coached by the Juilliard Quartet, especially its leader Robert Mann, and by Felix Galimir, another celebrated quartet leader.

Whisky A Go Go

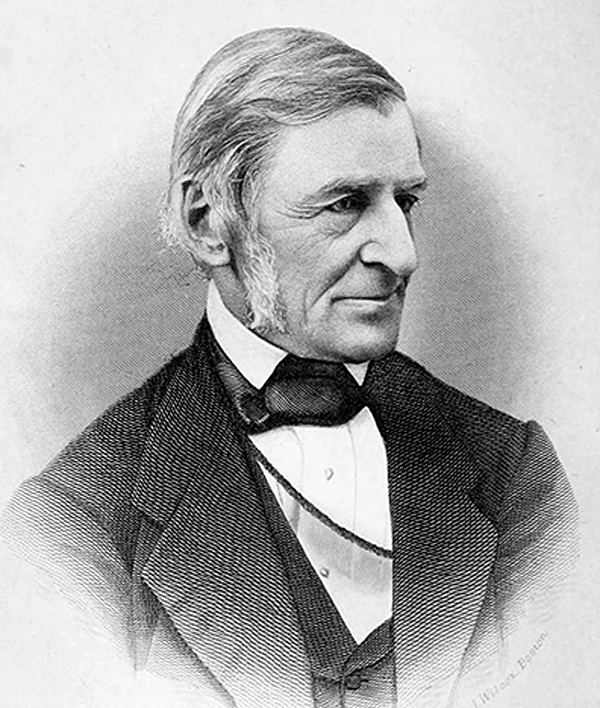

Six years later they began to tour as an ensemble having taken the name of the American poet and thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson. According to Drucker, they wanted a name that would say 'We're Americans who have the ability to play European music'. In 1977 they were joined by the violist Lawrence Dutton.

The following year the Emersons found themselves looking for a new cellist, and Setzer went to meet a promising candidate. David Finckel proved reluctant at first – 'I wasn't sure I wanted to be married to three men, as it were' – until Setzer opened a bottle of whisky. 'And the more Scotch I had the more agreeable I became to his suggestion', he said.

Witness accounts of the Emerson Quartet when in rehearsals – a heated debate over the balance of a chord in Beethoven's Op 127, say – testify to the mutual respect, the technical and intellectual equipment which both their recordings and concerts have manifested over the last 45 years. The ESQ make democracy work in action by overturning the accepted wisdom that a quartet requires a leader, a primus inter pares, to reflect the hierarchy implicit in the classical literature for the ensemble.

Instead, from college days, Drucker and Setzer alternated chairs, between pieces and across recordings (where it isn't always possible to tell who's sitting where). For some critics and listeners, this stratagem has proved the ESQ's 'fatal flaw'. Happily – I would say – they have stuck to their principles.

A Drucker-led performance is very often (not always – see the First 'Razumovsky' described earlier) a more rhythmically solid one, especially in Classical-era repertoire, more driven and rhetorically extrovert. Setzer's leadership finds its home in the ambiguous world of Shostakovich, where brittle observance of convention and frail despair are stitched into the fabric of the scores. If you want to hear a version of the Fifteenth played so that the flies really do drop dead in mid-air as the composer asked, Setzer and the ESQ are your men.

Until he left the group in 2013 to be replaced by Paul Watkins, cellist Finckel played the part of the straight guy to perfection (like Bernard Gregor-Smith for The Lindsays) – rock solid, seemingly imperturbable. Out on the right, Dutton never conformed to notions of the violist as musical mediator – unlike German groups such as the Hagens, individuality is as important as democracy in the Emersons' corporate identity.

Award Winning

Though they won attention and prizes soon enough, the Emersons came to make recordings slowly – and then all at once. Arthur Rubinstein's producer Max Wilcox became a fifth pair of ears and stringent sounding-board. The contract with DG, which they signed in the late 1980s, arrived at the right time for everyone concerned. The Emersons had a decade of performance under their belts, and the label wanted a pitch-perfect group to record the quartet canon for the CD format.

On their first album, Beethoven's 'Serioso' Op 95 comes tearing out of the blocks. The award-winning Bartók cycle made their international reputation in the early '90s with the same kind of glow and fearsome confidence as the Schubert 'Death and the Maiden' on that debut album, yet without rounding off Bartókian corners or smoothing over passages meant to sting. There have been more 'Hungarian'-sounding Fourths since 1989 – but more viscerally exciting ones? I don't think so.

There followed a Prokofiev album with a Mozartian lightness of touch, while Mozart's Flute Quartets (with Carol Wincenc) gained an earthy vigour beyond their usual rococo manners. The ESQ's trademark polish would in theory paint the quartets of Schoenberg and Carter on the richly coloured expressive canvas they deserve, but their engagement with new music has focused on the tonal end of American composers, and been under-represented on disc.

Outlier recordings of Harbison, Rorem and Schuller point to what might have been. Instead, it's time to remember rather than regret, and DG's ESQ box will stand as the definitive legacy for an ensemble that lived out the humanistic ambition of their namesake, always aiming above the mark.

Essential Recordings

Complete DG Recordings

DG 4795982 (55 CDs)

Not just for completists: a library of canonic quartets from Bach to Berg in first-class sound, unfailingly true to the score.

Schoenberg & Tchaikovsky

Sony 88725470602

The best of the ESQ's short-lived Sony partnership: a bitingly intense Souvenir de Florence and lushly textured Verklärte Nacht.

Schumann: Quartets Op.41

Pentatone PTC5186869

Drier in sound and approach than their DG recordings, tapping into the fragility as well as hot temper of Schumann's writing.

'The New York Concert'

DG 4836574 (2 CDs), 4837087 (2 LPs)

Back on DG, live from 2018 and drawing out the unbuttoned side of Evgeny Kissin in piano quartets by Mozart, Dvorak and Fauré.

Webern: Music for string quartet and trio

DG 4458282

Webern the romantic poet, the Expressionist tone-painter and modernist crystallographer, all sketched with sympathy.

Purcell & Britten

Decca 4815204

Perhaps the ESQ's most unlikely success: full-blooded commitment and vibrato searing Purcell's Chacony and fantazias with pathos.