Dvorák: 'New World' Symphony (No 9)

We associate 'cultural cringe' with the reluctant debt felt by Australians towards 'the old country' (the UK), but the term easily fits the rapture shown by the New York public in December 1893 after the hotly awaited premiere of what was greeted as 'the first American symphony'. Department stores began selling 'Antonín Dvořák' shirts, ties and walking sticks. Becoming a brand does not seem entirely to have bemused this butcher's son from Bohemia.

Patriot Act

The 'New World' also launched an American symphonic tradition, with more or less slavish imitations following rapidly in its wake, composed by the likes of Charles Ives, Amy Beach and Florence Price. And Dvořák gave his listeners every reason for their pulses to quicken with patriotic fervour: he had found inspiration, so he said, in the folk culture of his temporarily adopted home and in spirituals such as Swing low, sweet chariot alluded to during the symphony's first movement.

What Dvořák didn't say at the time – in public, anyway – was that American-Indian and African-American music was practically identical as far as he was concerned, and could just as well be Scottish: it was all (trigger word) 'ethnic' grist to his mill. During a visit to the Minnehaha Falls in Minnesota he came up with the much-abused theme of the Largo, and he seems to have planned the Ninth as a 'Hiawatha' symphony after the epic poem by Longfellow. The notion of the 'noble savage' embraced by both poet and composer has had its day, and the Ninth would probably be cancelled by now had Dvořák not wisely kicked over the traces.

Some of them, anyway. The Ninth shares its key of E minor with the Fourth of Brahms – always Dvořák's prime symphonic exemplar – as well as the scoring of the Scherzo with triangle. Handled gently rather than hustled through, the movement's trio evokes the ineffable nostalgia at the same point in Schubert's 'Great' C major. The A-B-A-B-A form (new for Dvořák, at least symphonically, with what amounts to a separate C episode during A) looks back to mid-period Beethoven and Mendelssohn.

None of this is especially American. And indeed Dvořák had been brought across the Atlantic in 1892 with his qualms settled by the promise of a great deal of money and the assurance that he could be just who he was, a Czech composer.

Writing the cheques was the formidable Jeannette M Thurber, founding president (in 1885) of the National Conservatory of Music in New York. She offered ten times his teaching salary in Prague on a two-year contract to become the conservatory's director, but he still haggled for the next seven months and eventually put it to a family vote. 'Mrs Dvořák and my eldest daughter, Otilie, are very anxious to see Amerika', he reported back to Thurber, and that was that.

Trouble Brewing

However, Thurber was spending her coffee-merchant's husband's money, which began running out just before the premiere of the 'New World' when his firm went bust. Dvořák maintained friendly terms and continued teaching while waiting for his salary payments to catch up, but he sailed back to Europe for a holiday in 1895 and politely declined to return. So much for the 'New World' as a symphonic note of homesickness.

How you hear it says as much about you as the piece. I hear it as wholly Czech, no less than the previous eight symphonies, looser in profile than Nos 7 or 8 (especially in the Russian-style finale, which substitutes elaborated repetition for development) but touched with points of genius such as the silences before the close of the Largo, which Mahler must surely have borrowed for the end of his own Ninth.

With its often weak first and strong second beats, Dvořák's rhythmic signature is inimitably Czech: an authenticator app, locking out most non-native and/or high-gloss recordings made by celebrities of the podium whose recordings of the 'New World' tell us more about them than they do about the piece (looking at you, Herbert von K). The 18-minute elegy of Bernstein's farewell Ninth in Israel (DG) is a guilty pleasure, but his '60s NYPO version (Sony) wears its years well for the care taken over hotspots such as chording and phrasing the brass chorale to open the Largo.

Modern listeners and interpreters (Dudamel on DG, Urbanski on Alpha) who are in search of maximum hi-def contrasts might bear in mind, too, that Dvořák's pianissimi and fortissimi are not the same as Brahms's, or Mahler's or anyone else's. Listening to generations of Czech-made performances makes clear that the slopes between soft valleys and loud peaks are gentler – grassier, even. The orchestral palettes of most German orchestras, even under Kubelík and Nelsons, are too dark and dense, though the Bamberg SO has made a pair of marvellously outgoing modern Ninths under Jakub Hrůša (Accentus) and Robin Ticciati (Tudor).

It follows that my subjective choice of 'Essential Recordings' [see opposite] could have been filled with Supraphon albums. That would be unfair on those listed, as well as a clutch of underrated but wholly idiomatic versions with British orchestras: LSO/Rowicki (Philips), LPO/Macal (CfP/Warner) and RLPO/Pešek (Virgin/Warner). Duff acoustics and engineering compromise Andrew Davis's beautifully pointed account from Toronto (Sony).

Horns Of Plenty

Period ensembles and conductors have been slow to embrace Dvořák, but the rewards of a historically informed sensibility in the piece are immediately apparent in the glowing horns of Immerseel's Anima Eterna ensemble (Alpha), the chirping flutes, bubbling clarinets and pliant strings: a big improvement on the acid palette of Krivine's Chambre Philharmonique (Naïve). Even more than Harnoncourt, Norrington (Hänssler) and Dausgaard (BIS) paradoxically bring the piece closer to Mahler than to Brahms – as it should be, from 1894 – with flexible phrasing which underlines the furiant character of the Scherzo while playing the bombast of the finale with a light hand.

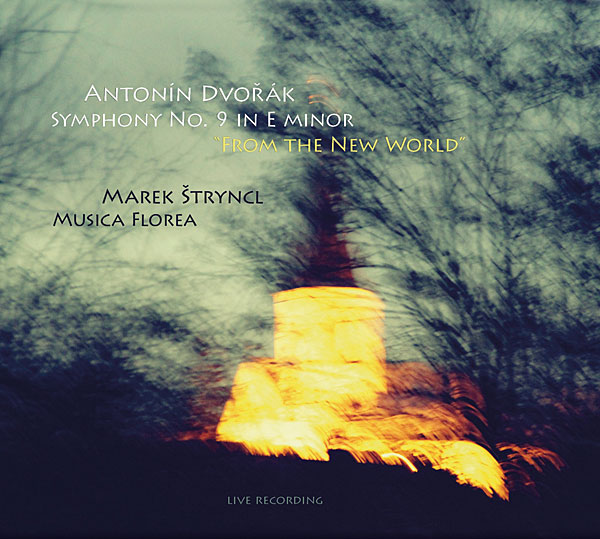

With a 30-year background in performing Czech Baroque and Classical repertoire, the Prague-based Musica Florea under their founder Marek Štryncl unite both varieties of authenticity, and the result is a joy. Nostalgia is always counterbalanced by a fierce sense of purpose and momentum. I love the snap of the finale's opening, its sense of pride and defiance without breast-beating, and Štryncl's freedom in turning up the heat for the second theme. Whichever world it comes from, this is a Ninth that sounds new in every bar.

Essential Recordings

Czech PO/Talich

Supraphon SU38332

Dim mono and wobbly pitch, but this 1954 version still takes a snapshot of Dvorák's (new) world as vividly present as any other.

Czech PO/Ancerl

Supraphon SU36622

Sounding taut and fiery as ever in up-front Iron-Curtain stereo from 1961, with a deeply invested but songful Largo.

Prague SO/Mackerras

Supraphon SU38482 (CD) SU43011 (3LPs)

Richness and depth for the vinyl remaster of Mackerras's final recorded thoughts on a piece he'd conducted for half a century.

Detroit SO/Paray

Mercury/Presto 4343172 (1CD),

Eloquence 4843318 (22CDs)

A wild ride, gripped with tension throughout, sounding better than ever in the new 'Mercury Masters' Paul Paray box set.

RCOA/Harnoncourt

Warner 9029673082 (LP)

Opulent 'Old World' colours from Amsterdam, newly minted, score-led but always affectionate shaping from the conductor.

Musica Florea/Štryncl

Arta F10230

A live, up-to-the-minute and ear-opening 'New World' full of local colour and drama.