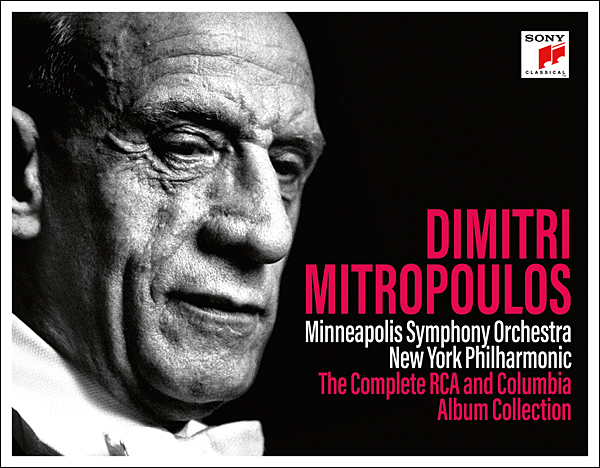

Dimitri Mitropoulos: Olympian Maestro

Leonard Bernstein once addressed the 'art' of conducting in scientific terms, saying it required 'an inconceivable amount of knowledge', 'a profound perception of the inner meanings of music' and 'uncanny powers of communication'. More ambitiously, 'the conductor must not only make his orchestra play; he must make them want to play. He must make the orchestra love the music as he loves it'.

Gloves Off

Leaders the world over will fantasise about inspiring not only commitment but devotion from those over whom they exert power, and conductors are no different. But Dimitri Mitropoulos fits Bernstein's description as well as anyone.

As a recent émigré he had given a Boston SO concert in 1938 which electrified the Harvard graduate student. He took Bernstein under his wing, though the ambitious younger man later repaid his kindness by angling to replace him as the head of the New York PO.

Herbert von Karajan, too, paid rare tribute to the way in which music seemed to flow through the Greek conductor and communicate itself to both players and audiences. At Karajan's behest, Mitropoulos became a welcome return guest at the Salzburg Festival in the last years of his life, as documented on Orfeo. Mitropoulos exercised a formative influence on the two most dominant conducting egos in the second half of the last century.

By contrast, their mentor was humble to a fault. Mitropoulos gave away most of his earnings, lived simply and relied on the kindness of friends when ill health forced him on hard times. He saw orchestral musicians as his colleagues in search of truth rather than underlings, and his hands-on technique resisted the traditional hierarchy which placed ultimate power at the tip of a baton like a military general. 'Conducting with a baton is a bit like playing the piano with gloves', he claimed.

Dark Star

Born in Athens in 1896, Mitropoulos grew up in modest circumstances as the son of a leather-seller. He began composing in his youth, including an opera which impressed Saint-Saëns, and he went to Berlin to study with Busoni. His own creative activity survives largely in the form of Bach transcriptions: imposingly Gothic in character, much darker than Stokowski's arrangements, temperamentally drawn to the gaunt, minor-key organ preludes and fugues like the G minor BWV 542.

For many years, Mitropoulos fans have had to bow to the wisdom that he was best caught live, either in the flesh or by broadcast recordings, because so little was available to suggest otherwise. Such a notion is seriously challenged by a recently released box set which brings together all of the conductor's studio recordings for RCA and Columbia (now part of Sony) made during his tenures in Minneapolis (1936-49) and New York (1950-57).

Eager To Please

Never the most technologically advanced of labels, CBS made do with suboptimal venues. 'You've never heard so much sound', remarked the producer Howard Scott while recording Shostakovich 10 shortly after the NYPO and Mitropoulos had given the US premiere. 'We may even have to send some of the men home. Studio can't always handle it, you know.' Ever eager to please and make everything right, Mitropoulos was a cooperative but edgy recording conductor: 'What's wrong? Tell me, what's wrong?' he demanded of Scott.

It was his misfortune, and ours, that he died before the golden age of stereo. Excerpts from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet in 1957 are our best record of what might have been. We might also have a much fuller account of the conductor in canonic repertoire had he not been so determined to press the cause of contemporary composers, had he been as assiduous at building a legacy on record as many of his colleagues, and had CBS placed more faith in the conductor.

Wild Ride

Mitropoulos was blessed with a photographic memory which allowed him, once a score had been learned, to see every part of it in the mind's eye while conducting. Not that this produced dryly analytical performances: far from it. Listeners had to strap themselves in for a wild ride, and American and English critics were sometimes unseated by the velocity, the unpredictable corners and impact of his readings and the acoustic pressure that he elicited from an orchestra.

Music of a heroic-tragic cast from any era drew the best out of Mitropoulos. Mozart's Thamos incidental music and Idomeneo overture; the D minor Piano Concerto of Brahms (see Essential Recordings, opposite); Strauss's Elektra and Berg's Wozzeck, which scored an unlikely triumph with conservative New York audiences. All these pieces are driven as if by some demon at their heels. When he exults, in the Haydn Variations of Brahms, Petrushka and the Emperor Concerto with Casadesus, it is with a fierce joy – Mitropoulos conducted everything at gas mark 10.

Symphonies wound tight with motivic interconnections also found the conductor in his element: Schumann 2, VW 4, Franck, Berlioz and most of all Mendelssohn's Scottish, both in the studio for CBS and in concert – with the BPO in Salzburg on Orfeo, and the Cologne RSO in what became his final concert, given in October 1960.

Sure Instinct

Mitropoulos died less than a fortnight later from a heart attack he suffered while rehearsing Mahler 3 in Milan. As much as any of the music cited above, he was seemingly a born Mahler interpreter, unfazed by the technical demands of the symphonies, in tune with their visionary ambitions and unselfconscious outpourings of emotion. Here too, though, he was 'swimming upstream', as one New York critic described it. Mitropoulos pressed the composer's cause in his only meeting with Toscanini and was told in reply that a Mahler score was fit only for toilet paper.

Even while his relations with the New York PO broke down – rebellious players and sceptical critics playing their part – Mitropoulos spent more and more time in the pit of the Met, refreshing verismo staples by Puccini and Mascagni with a sure instinct for pacing and a sensitive ear to his singers. Tempi that would sound breathless in the hands of other conductors supported the human flow of the narrative, such as a three-hour Walküre (on Walhall).

As a gay man who kept his homosexuality to himself, he invested his work with a kind of sexual energy that Karajan and Bernstein emulated for themselves, but also with a selfless dedication that was all his own. As he wrote in 1952: 'Music is another expression of my unlived sexual life'.

Essential Recordings

Complete RCA & Columbia Collection

Sony/BMG 19439888252 (69 discs)

The essential starting-point, documenting tenures in Minneapolis and New York and the DM white-hot studio technique.

Strauss: Elektra

Guild GHCD 2213/14 (2 discs)

Not the most complete but the most engulfing of his Elektras, featuring Astrid Varnay on blistering form, live in New York.

Puccini: Madama Butterfly

Walhall WLCD0297 (2 discs)

Tight and subtle, the best of his Met work, live in 1957 with Dorothy Kirsten: living drama instead of schmalz.

Schumann, Prokofiev: Symphonies

Orfeo C627041B

An uneven but unforgettable Salzburg Festival debut: bear with the rough-edged Prokofiev 5 for a searing Schumann 2.

Mahler: Symphonies 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9 & 10

Music & Arts CD-1021 (6 discs)

Tip-top remasterings of Mitropoulos live and unleashed in music he made his own, including a sensational Fifth.

Brahms: Piano Concerto No.1

Music & Arts CD-4990

A rare example of Mitropoulos finding a soloist (in William Kapell) prepared to take the same risks. Blazing, elemental Brahms.