Carlo Gesualdo: Prince Of Darkness

Denis Stevens was a British musicologist who, in the early 1960s, began persuading people to listen to Gesualdo's music rather than marvel at the composer with horrified fascination. One night, after rehearsing the Sixth Book of Madrigals, he was so stunned that on his way home he caught the right train going in the wrong direction.

Contrast that with the reaction of musicologist Alfred Einstein when gingerly leafing through the pages of Book 6: 'It is impossible to sing three such pieces one after the other without being seized by a sort of nausea or musical sea-sickness, for the dose is too strong and the unsteadiness too prolonged'.

The Cook, The Thief...

Readers of HFN are made of stronger stuff. But I wonder whether Einstein would have felt his stomach turn without prior knowledge of Gesualdo's infamous life-story. To recap, he was born around 1560 in Venosa, just east of Naples, the second son of Duke Fabrizio Gesualdo. By 1590 he was heir to the throne, and married to Donna Marie d'Avalos (herself already twice widowed, still in her 20s). Finding her in flagrante delicto, he murdered both his wife and her lover.

The bodies were then publicly displayed according to Don Carlo's orders with a placard explaining the tragedy. Suffering, so it seems, more from private guilt than criminal censure, he married again in 1595. Meanwhile Gesualdo had thrown himself into music with the same obsessive fervour that he conducted all his affairs. The composer Cavalieri met him early in 1594. 'The Prince of Venosa, who would like to do nothing but sing and play music, today forced me to visit him and kept me for seven hours. After this, I believe I shall hear no more music for two months.'

Until his death in 1613, Gesualdo lived as a recluse in the family seats of Venosa and Gesualdo. He left behind six books of madrigals, and sacred motets including the three sets of Tenebrae responsories for the penitential liturgies of the Triduum, on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday.

Gesualdo was not an Easter Sunday man. Light does not conquer darkness in his music, and life does not overcome death, even though music is by its nature an expression of life. The Tenebrae are an apt liturgical metaphor for his style. They occupy a liminal space between crucifixion and resurrection. The later madrigals are written not within key signatures but in between them, across the boundaries of consonance and dissonance.

Unmistakable Craft

Not all his music is like this. If all Gesualdo knew how to do was break the rules, he would be another sad and sordid but forgettable misfit. The First Book of Madrigals opens with a sensuous but decorous setting of 'Baci soavi e cari' (Dear, sweet kisses). As it continues with finely drawn portraits of noble ladies, shepherd girls, love affairs frustrated and consummated, the volume would hardly sound out of place in the catalogue of other first-rank Italian madrigalists such as Marenzio or Luzzasco.

From the outset, though, the craft is unmistakable, almost unrivalled among his contemporaries. If Gesualdo had an apprentice period – and he must have learnt from someone, at some point – we have no record of it. Such biographical holes only serve to enhance his mystique. Poets of the day rushed to re-tell and invent his life with the enthusiasm of door-stepping tabloid journalists. In our time, eight operas about Gesualdo have appeared in the last 30 years. There is more music about and inspired by him than the total of his extant output (around ten to 12 hours), much of it unworthy of its subject, trading off his 'modernity'.

Stravinsky knew better. The eight-minute Monumentum pro Gesualdo [see Essential Recordings] transcribes and recomposes three pieces, sounding entirely like both composers at the same time. The Werner Herzog documentary (Gesualdo, Death For Five Voices) also captures something true and slightly deranged and essential to our understanding of both the music and the man. It stars the folk/pop/avant-garde singer Milva as a reincarnated Donna Marie, two cooks and the staff of a mental health clinic where patients believe themselves to be Gesualdo.

The very first recording of Monumentum, on CBS, featured a Side A of Robert Craft conducting Gesualdo originals. In 2024, it shows how singers and listeners like Einstein could indeed find themselves entirely at sea in music for which there was no established performing style. My first encounter with Gesualdo's music was a 1967 Das Alte Werk LP of the Prague Madrigal Singers in the Holy Saturday Tenebrae Responsories. Where the dissonances on the page end and the wobble in the voices takes over, who can say?

The best Gesualdo recordings evoke austerity and opulence in equal measure. They may exploit the generous resonance of a church or the analytical intimacy of a radio studio. Too much echo, and the harmony blurs. Too little space, and every last vocal blemish stands out.

Of course, performers don't have to be Italian to make sense of Gesualdo, of the madrigals in particular, but it seems to help. Italian ensembles are still overcoming a persistent chauvinism in the field of early music, but groups like Delitiae Musicae, La Compagnia del Madrigale and La Venexiana combine pinpoint tuning with a native feeling for text and phrase, for the swooping and dipping lines and for those moments when a suspension wants to be touched in or drawn out.

All Too Human

Even so, a late madrigal such as 'Gioite voi, col canto', opening the Fifth Book, invites a spectrum of approaches as broad as a Mahler symphony. The Consort of Musicke leap through its hoops. La Venexiana impart a healthy swing to the pulse that holds the listener's ear across metrical breaks and abrupt paragraphing. Les Arts Florissants go for word-by-word-painting of the text's intermingled joy and sorrow. Concerto Italiano aim for a more sensuous blend, palpably directed into and away from climaxes by Rinaldo Alessandrini. My own taste runs to Delitiae Musicae, slower than most, caressing each phrase, though the all-male range of vocal colour won't appeal to everyone.

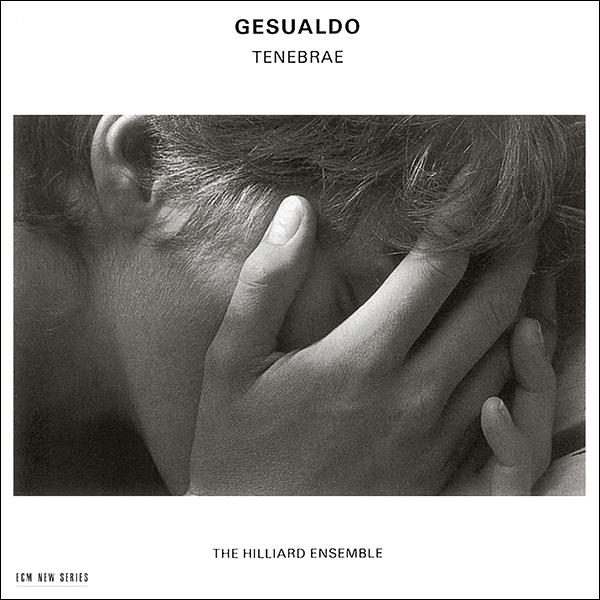

By virtue of their Latin texts, their less exotic harmonies and more readily comprehensible syntax, the Tenebrae respond to a wider field of performers. Again, the all-male lineup of the Hilliard Ensemble imparts a force and sobriety in tune with the acoustic of Douai Abbey. They capture what is deeply human and alien about this music, while their fervent declamation resists the old pull towards solemnity. Encapsulating his predecessor, Stravinsky quoted Alexander Pope: 'The lights and shades, whose well-accorded strife...'.

Essential Recordings

Tenebrae Responsories

ECM 8438672 (2CDs)

Two hours of aching, suspended dissonance, the Hilliard Ensemble's rich voices cloaked in a suitably resonant church acoustic.

Gesualdo, Tallis, Bingham

Hyperion CDA68348

The Gesualdo Six Ensemble in warmer, more intimate accounts, insightfully paired with later English responses to the texts.

Monumentum pro Gesualdo di Venosa, etc

Pentatone PTC5186349

Stravinsky's instrumental tribute, coupled with choral works (the Mass and Psalms) in suitably austere accounts under Herreweghe.

Madrigals, Books 5 & 6

Naxos 8573147-49 (3CDs)

Culmination of Gesualdo's madrigal writing from the Italian ensemble Delitiae Musicae, attentive to subtleties of text and setting.

Madrigals, Book 6

Glossa GCD922801

A fuller, more passionately declaimed but poised response to the same pieces from the native voices of La Compagnia del Madrigale.

Psalmody, Carlo, L'Ombra della croce, etc

ECM 4811800 (2CDs)

Contemporary responses to Gesualdo, by Brett Dean and Erkki-Sven Tüür, blending Renaissance and modern sensibilities.