Brahms: Piano Concerto No 1

Picture yourself sitting in the audience at the earliest performances of the D minor Concerto, in January 1859, the 25-year-old composer at the keyboard. Imagine that the contemporary piano concerto meant Liszt and Litolff: glitter and fluff, brevity and showmanship. How would you take to the epic first movement, itself as long as several whole Mozart concertos? No wonder that it was hissed in Leipzig – Brahms wrote off the event as a brilliant and decisive failure.

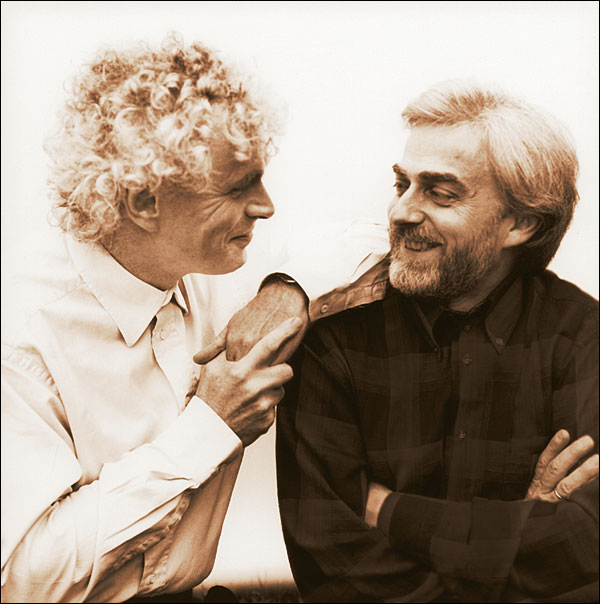

It Takes Two

Much of the angst surrounding the piece derives from its tortuous gestation. Brahms first met Robert and Clara Schumann as an ambitious 20-year-old. The couple took both to him and to the works he brought them. Brahms proceeded to compose a sonata for two pianos, and then orchestrated the first movement as a toe in the water towards writing a First Symphony. He wrote to Clara of a dream in which he had used his proto-symphony for a piano concerto instead.

HMV caught Wilhelm Backhaus in his prime when they made the first recording of the First Concerto, in 1932. Sir Adrian Boult lays down the gauntlet in a mighty opening tutti, conducting the BBC SO, but the forward movement and flexibility of the movement as a whole (over in 19 minutes) are a world away from the solemn weight of many postwar recordings. As a boy, Backhaus had met the composer in 1895, at a Leipzig concert when he conducted Eugen d'Albert in both piano concertos in a single evening, thereby setting an unfortunate precedent for a musical circus act that has been perpetrated in our own time by Daniel Barenboim and others.

The example of Backhaus, meanwhile, is one followed by many fine young pianists of the next generation, balancing dynamism and nobility in the first movement, never becoming bogged down in the lyrical episodes, drawing on all the latent Beethoven and Bach which Brahms encoded in the profound slow movement, and then giving a Mozartian spring to the finale's intricate counterpoint.

No less than hungry keyboard lionism, however, the First Piano Concerto demands a symbiotic relationship between soloist and conductor in order to realise the symphonic dimensions and dialogue of a work with Beethoven's 'Emperor' as its only precedent. As well as being played on the quicker side, it's probably no coincidence that most of my favourite recordings [see Essential Recordings, p79] were made in partnership with conductors at home in modernist as much as Romantic repertoire. The most staggering performance I ever saw live was given by Maurizio Pollini and the LSO, working with the unlikely figure of Péter Eötvös, who apparently later said the concerto was harder to conduct than the complex piece of Lachenmann he had led in the first half!

Caught On The Wing

Live or as-live does seem to be the condition that draws out the best of most pianists in the piece. There was surely no audience present when the 25-year-old Julius Katchen recorded it for broadcast in 1951 with the SWR Baden-Baden SO and Ernest Bour (now on Urania), but there is no shortage of Hungarian fire (or wrong notes) to the outer movements, and mutual, inward communion in the Adagio. Like Backhaus, Katchen presses on ardently in the first movement's lyrical second theme where many later pianists sit and linger.

Bour's predecessor at Baden-Baden was Hans Rosbaud, another under-rated, modernist-inclined maestro, whose suavely Classical approach lends crisply disciplined support to Walter Gieseking and (especially) Rudolf Firkušný, in more 1950s German radio recordings, reissued on the SWR Classic label.

Youth is hardly a prerequisite, but there is something to be said for taking the piece head-on with the fearlessness of inexperience: see William Kapell and Dino Ciani in 'Essential Recordings' below, both pianists (like Katchen) whose flame now seems to burn the brighter for being extinguished before its time.

While there are touches of self-conscious grandeur to Bruno-Leonardo Gelber's recordings from the '60s as a 20-something tyro, his thoughts are fresher and his fingers lighter than his fellow Argentine Daniel Barenboim, who has recorded the piece more than anyone else in the modern era. Counting live performances, however, the Chilean Claudio Arrau tops the list with eight (at least) accounts on record, all of them centring on a slow movement of fathoms-deep touch and yet dappled shades of autumnal colours.

First thoughts on the piece are often best. Clifford Curzon's later recordings with Jorda and Szell are no improvement on the rhapsodic flow of his 1953 account (also on Decca, now Eloquence) with van Beinum and the Concertgebouw, so well matched tonally and boasting a first horn as eloquent as the pianist. I confess myself allergic to Szell's conducting, whether accompanying Fleisher, Serkin or anyone except Schnabel back in 1938 (Naxos), when he had not yet become so unyielding of pulse and so domineering as a personality.

I can hear the mono-phobes rustling in the stalls. What about a version in fabulous stereo worthy of my kit? Gilels and Jochum on DG once held sway as a benchmark: aristocratic, eloquent but too drawn out. Berman with Leinsdorf on Sony: technique at the service of the pianism rather than the piece, though he does buck the trend (in 1980) for performances to drag in search of profundity. Pollini's remakes with Abbado and Thielemann again do not add to the fire-and-ice of his first version with Böhm ('a kind of miracle', he recalled of their partnership).

Second Thoughts

However, several recent 'second thoughts' from notable Brahmsian pianists have brought new insights to the piece. Stephen Hough's Virgin Classics recording had an appealing, Mendelssohnian freshness of phrasing, but the Hyperion remake is much better integrated with the Salzburg Mozarteum orchestra. Krystian Zimerman's first version on DG is dominated by Bernstein on the podium; he finds a partnership of symphonic equals with Rattle, yet some will find the level of detail, sonic and interpretative, distracting.

Best of all, in terms of our own time, there is Sir András Schiff on a Blüthner piano from 1859, the year of the concerto's premiere. The generically Romantic flourishes of accompaniment from his early Decca version with Solti are replaced by much subtler gradations of portamento and vibrato, call and response, from his long partnership with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and their Abbey Road studio version retains the thrilling spontaneity of the London concert I saw, in which Brahms the young lion roared once more.

Essential Recordings

Kapell; NYPO/Mitropoulos

Music & Arts MACD0990

A crumbly but electric radio broadcast from 1953, a reading of alarming extremes and a true meeting of minds.

Ciani; Hungarian RTVSO/Abbado

Stradivarius STR10014

Another lo-fi, high-intensity treasure from the archives, and one in which the two young Italians spur each other on.

Arrau; USSR RSO/Rozhdestvensky

Doremi DHR7890-91 (2CDs)

Cavernous mono recording, more ropey accompaniment but detailed conducting; and Claudio Arrau at his most towering.

Brendel; BPO/Abbado

Decca/Philips 4200712

Alfred Brendel's reading subtly gathers unstoppable momentum; Abbado and the Berliners offer sinewy support.

Zimerman; LSO/Rattle

DG 4775413 (CD), 4796867 (LP)

Old-fashioned in its spacious approach, yet entirely modern in the transparency of playing and engineering.

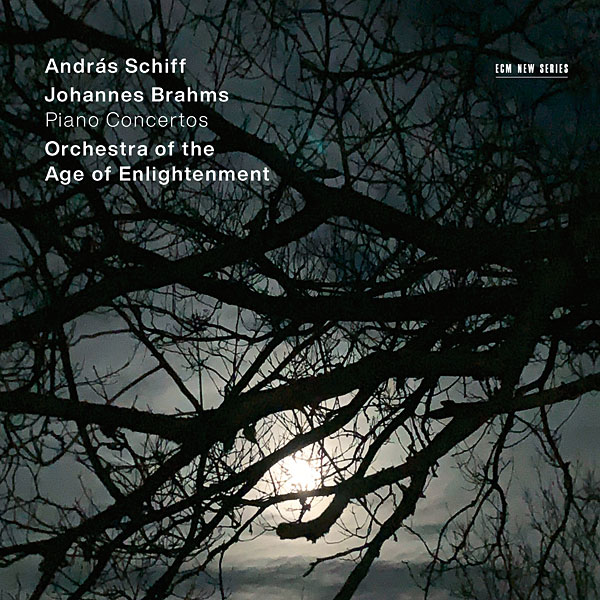

OAE/Schiff

ECM 4855770 (2CDs)

Authentic as in true to the spirit as well as the sound of the score, flowing like a molten river in the outer movements.