Beethoven: Symphony No 2

Two years after the First Symphony, completed in 1800, Beethoven made a different kind of statement with the Second, on a grander scale, evident from the emphatic proclamation of D major rather than the First's quizzical gambit which deliberately contradicts its stated key of C. The Second seems to have been the longest symphony (by number of bars) composed up to that point in the genre's relative infancy – though Beethoven may have had in mind the spacious grandeur of Mozart's final symphony in D major, the 'Prague'.

Scurrying Cascades

Beethoven's gain in confidence as a symphonic writer is exemplified by the Adagio introduction with its tremendous variety of textures: scurrying cascades and arabesques, a steady pulse, a woodwind melody punctuated by jabs in oboes and horns and unexpected accents.

The development section of the first movement is much more extended than in the First Symphony, and it introduces a march – a revolutionary one? Certainly one with a jaunty, French character. Beethoven is much more daring than hitherto in terms of quick changes of harmony and texture and a strong, almost operatic sense of gesture. The Haydnesque pause before its stealthy continuation into the recapitulation is just as ingenious in its way as the Third's notorious false start at the same point.

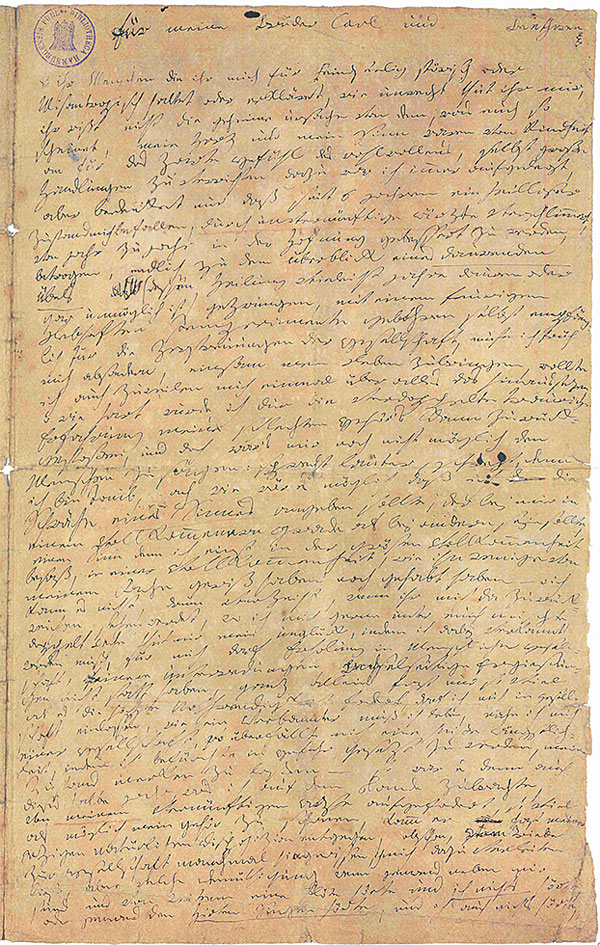

In terms of interpretation, the hot potato of the Second is undoubtedly the Larghetto. Until the Ninth's Adagio, no symphonic movement of Beethoven gives rise to more different performances in terms of both tempo and expression. Playing it at the metronome mark (which was added much later by Beethoven) draws from the page a flowing nocturne just over nine minutes in length, inflected with introspection and melancholy, still with plenty of room for various characterisations (or lack thereof!).

Proponents of 'new objectivity' such as Scherchen (Westminster/DG) and Leibowitz (once on Reader's Digest records, now in an essential-listening big box from Scribendum) began to make historically aware recordings of Beethoven's symphonies back in the 1950s. It doesn't (or shouldn't) take a knowledge of them to grasp that when played out as a solemn hymn, between 12 and 14 minutes long, the Larghetto loses much of its charm and becomes a duller piece.

The Second brings out the best from interpreters in touch with the spirit of comedy, whatever their vintage or chosen tempi. Thus Knappertsbusch (live in Bremen) cuts a more elegant dash through the piece than another 'new-classicist', Hans Rosbaud (SWR). Even this generalisation has its limitations. Günter Wand surely conducted far less comic opera in his career than Karajan, nor was he known for more than a very mordant sense of humour, but his digital-era Second (RCA/Sony) is superbly timed and detailed in all four movements.

Italian Model

In fact Karajan and Wand stand out among their contemporaries for their grasp of the Larghetto's mood and sensibility. Timings tell only a fraction of the story, but almost all the most naturally phrased and eventful performances of the movement come in around the ten to 11 minute mark (excepting Brüggen, whose second, late cycle of the symphonies on Glossa breaks all the rules while inventing new ones rather as Beethoven's music does).

It may be no coincidence that both conductors held Toscanini as their model above all others, and while the Italian maestro's Beethoven could be unyielding on occasion, his fiery temperament and his drive for precision are admirably suited to the Second. The other outstanding conductor of the Second in the mono era was Sir Thomas Beecham (in stereo on EMI/Warner, but more trenchant in 1956 on BBC Legends). Both men were also instinctive interpreters of Rossini, and they grasp that avoiding lethargy in the piece doesn't entail playing it for laughs: both of them nail the bristling momentum of the first movement and the edgy, opera buffa subversiveness of the finale.

Musical Mirth

Humour in music is even more difficult to capture than to describe, but it's a prerequisite of the Second. Beethoven made (or at least supervised) a piano-trio transcription of the symphony: the Faust/Queyras/Melnikov version on Harmonia Mundi being effortlessly stylish and funny. The byplay of the voicing in the arrangement of the Scherzo could teach a few conductors about how the full version should go, and this is where otherwise muscular versions by the likes of Mitropoulos and Steinberg sound heavy-handed by comparison, though some modern versions (for example, Chailly on Decca, Adam Fischer on Naxos) leave no room for the jokes to land.

In the modern era I associate the Second with Jansons and Norrington as much as anyone, including the conductors listed in our Essential Recordings [see opposite]. The frequency of its appearance on their programmes suggested an innate sympathy confirmed by their recordings (go for the final thoughts in both cases, recorded on BR-Klassik and Hänssler respectively). They both relish the garrulous humour and bizarre contrasts of the Trio, and they both capture the tenderness of the Larghetto without lapsing into the jog-trot triviality of some up-tempo modern versions.

The ups-a-daisy gesture to launch the finale and its endless up-and-down string figurations always put me in mind of Mozart's Figaro, and more specifically the second-act finale with Basilio and his broken flower pot and one reversal of fortune after another.

Blazing Light

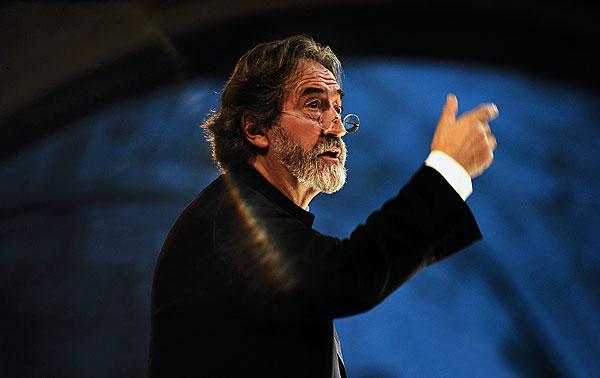

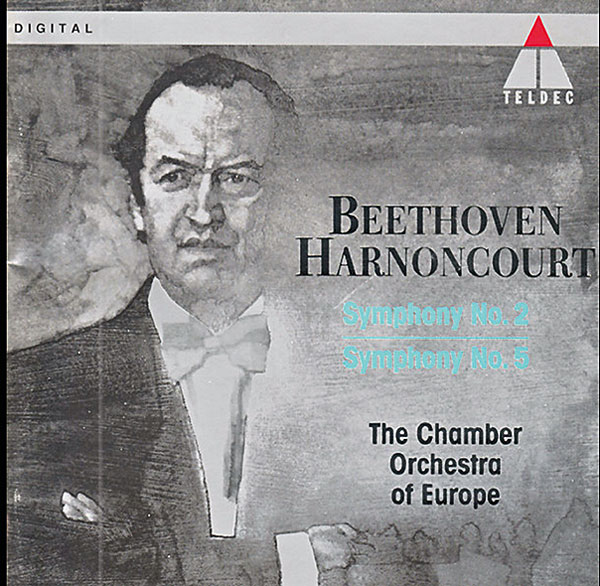

As an ambitious but politically motivated 20-something, Beethoven had already demonstrated his belief in Enlightenment values with words and musical deeds, and the Second is as much a manifesto in this regard as the Napoleonic Third. In holding all these elements in balance, it is the Austrian conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt who reigns supreme. While Zinman springs any number of quirky surprises with his unwritten ornaments and offbeat phrasing, Harnoncourt invests the Second with heroic and comic aspirations, so that the reach of the Eroica does not, after all, feel more than a year away in Beethoven's symphonic thinking.

The searing arrival of the COE's trumpets at the climax of the first movement brings blazing light and revelation to rival anything in the supposedly 'deeper' odd-numbered symphonies. I also love the sudden flurry in the finale's coda as the music seems to fall off someone's stand: another Figaro moment, a happy chance and entirely in keeping with the unpredictable spirit of the Second.

Essential Recordings

COE/Harnoncourt

Warner Classics 0927497682 (5 discs)

Currently a bargain on CD: the live, award-winning cycle from 1990-91 with the Second as the jewel in the crown.

NBCSO/Toscanini

Music & Arts MACD1275 (5 discs)

Full-bodied 2013 transfers of the 1939 cycle rated as the most incandescent of the conductor's Beethoven recordings.

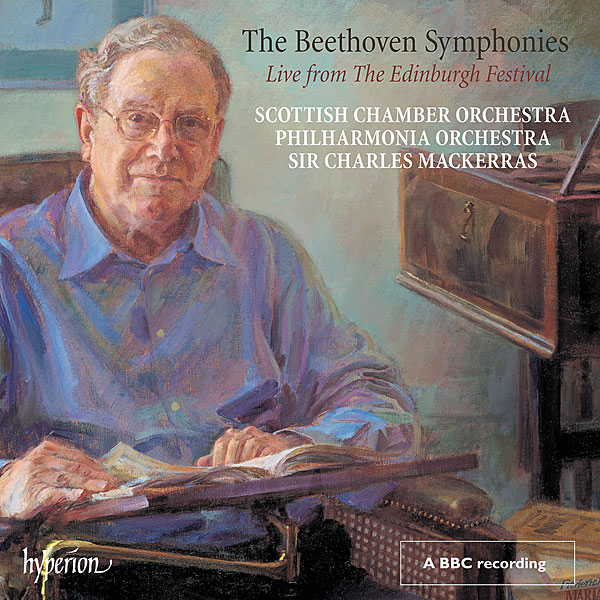

SCO/Mackerras

Hyperion CDS44301/5 (5 discs)

Recorded live at the 2006 Edinburgh Festival with an exceptional mutual understanding between conductor and players.

O18C/Brüggen

Glossa GCD921116 (5 discs)

A lifetime's learning distilled into live recordings which wear their wisdom lightly, especially in this Mozartian Second.

Le Concert des Nations/Savall

Alia Vox AVSA9937 (3 discs)

Spaciously recorded in a medieval Catalan fortress, filled with sunny humour and jest in the best Beecham tradition.

BPO/Rattle

Berlin Philharmonic BPHR160091 (5 discs)

Superbly engineered and powerfully built in the Berlin tradition, but also surprisingly nimble and charged with explosive wit.