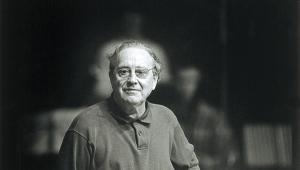

Luigi Nono Venetian radical

Classical heroes, Communist ideology, the lapping waves of a lagoon... Peter Quantrill explores the disparate origins of Nono’s sound-world though a rich recorded legacy

Politically charged modernism must be the least fashionable, most lazily derided category of music in the present day. This is a curious state of affairs. In the field of art, such idealism is everywhere – it’s almost obligatory. Beethoven and Wagner earned the label, in their own day, and in their different and complicated ways. It would be idle to imagine that Luigi Nono will one day attain their popularity. Yet, like them, he captured in sound what it means to struggle for change, for beauty, for a more just and compassionate world.

Fire from the gods

Nono was born a century ago, in Venice. There has been a slew of classical anniversaries to celebrate in 2024. Even so, for his centenary to pass with so little fanfare or devotion to his memory says less about the qualities or difficulties of his own music than it does about the pervasive timidity of the values he sought to challenge. He belongs (no less than Beethoven or Wagner) in the tradition of figures dating all the way back to Prometheus, the hero of classical mythology who dared to steal fire from the gods and was then punished for his hubris.

Prometheus still brandishes a flaming torch in Nono’s output. Prometeo is the title and subject of the composer’s largest, boldest and most mystical work. Subtitled ‘a tragedy of listening’, it scatters performers in groups across a grand space, in an updating of the polyphonic ensembles marshalled in St Mark’s Basilica, four centuries earlier, by Gabrieli and Monteverdi. Nono was no less profoundly a Venetian composer than he was a Marxist and perennially disillusioned member of the Italian Communist party.

Experienced live – I saw the belated UK premiere in 2008 – Prometeo teases the ear with harmony on the verge of extinction. It does not transfer readily to record, though the forces of the Teatro Regio Parma give their all. The text weaves together Aeschylus with Hölderlin and Walter Benjamin, not that those names fulfil more than a symbolic presence. Instead, especially on headphones, sung and instrumental textures blend, shimmer, recede and occasionally crash over the listener.

‘Listening’ becomes too passive a word to capture what the piece both requires and invites of us. It’s not so dissimilar, in this way, to Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, but much more attuned to an Italianate sensibility for the translation of moving light and water into sound. With the composer’s approval, Claudio Abbado made a kind of pocket Prometeo, but the sheer reach of the piece cannot be boiled down to a 25-minute suite.

The power of protest

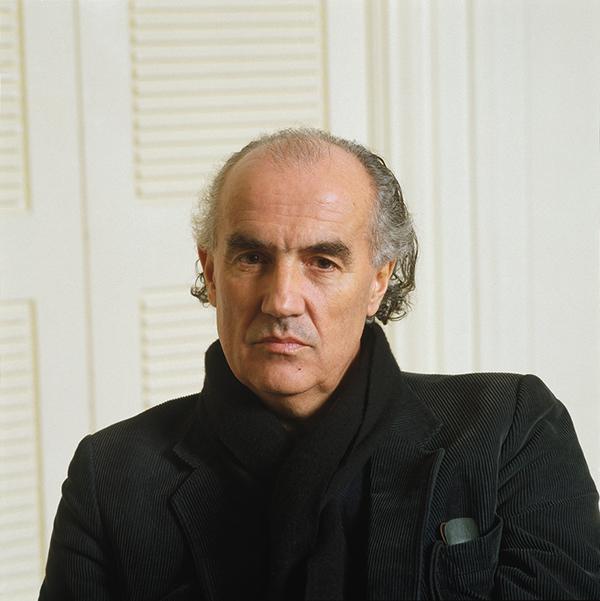

Better, instead, for Nono newcomers to head back to Abbado’s classic DG album from 1974, headlined by Como una ola de fuerza y luz. ‘Like a wave of strength and light’: Nono wrote this cantata-like homage in memory of a young Chilean activist, Luciano Cruz. A soprano functions as coloratura priestess and mourner, charging his name with hieratic power.

A piano part written for Maurizio Pollini fills the space below with the tolling of angry bells. The notes are all different (all wrong, some would say) but the expression reminds me of Verdi and La Forza del Destino, burning with justice.

More stylishly tailored to Pollini’s pianism was a solo sequel from 1977, ...sofferte onde serene..., which evokes Venetian bells across the lagoon. Nono had no use for ‘bourgeois’ ideas of melody or continuity in construction, but (as in Prometeo) the listening ear may find connections with Liszt’s late and haunting tone-paintings of ‘La Serenissima’, like La Lugubre Gondola and R.W. Venezia (Wagner again).

Meanwhile the Spanish title of Como una ola leads us to a series of late pieces from the 1980s, satellites around Prometeo, taking for their theme the phrase Nono found on the wall of a Toledo monastery. Caminantes, no hay caminos. Hay que caminar: ‘Pilgrims, there is no path, yet you must walk.’ Take it as a motto for listening to Nono, and you cannot go far wrong. No longer timed to synchronise with electronic-tape parts, these ‘caminar’ pieces allow greater liberty in performance, and accordingly have attracted more recordings.

Take courage

They culminate in the last work he wrote before his death in 1990, for two violins, and the burning hot stillness of central plains comes to mind as vividly as it does in the travelogues of Norman Lewis. You can ‘read’ Hay que caminar sonando III as the journey of two companions, or (perhaps more Nono-like) as the sensation of an uncharted territory with only your courage to guide you.

Abbado and other fellow travellers have done what they could with the big dialectic works of protest such as Il Canto Sospeso and Intolleranza 1960. They are worth revisiting, whatever the colour of your politics, not least for a three-dimensional approach to word-setting that has more in common with King Crimson or American poet Robert Lowell than with ‘classical’ songwriters such as Schubert or Nono’s father-in-law Schoenberg. One idea does not always have to follow on from another like a piece of Ciceronian prose.

Even so, and in that spirit of poetical fantasy, it is the more abstract or less overtly political pieces that speak most directly to our times. Fragmente – Stille, an Diotima is another chamber piece on the path to Prometeo. It’s Nono’s string quartet, if you like, as if he had edited down Schoenberg’s Fourth Quartet and left only the notes he liked the most, clustered in flurries and gestures around pauses for thought. In that way, the construction as much as the title irresistibly evokes the presence and distance of a beloved, referenced in the score by quotations from Hölderlin’s poem Diotima.

Another refrain in the score is that most Beethovenian of markings, mit innigster Empfindung – ‘with innermost expression’. This is not some metatheatrical gesture: Nono means it. As with Schoenberg, playing the music as a set of disconnected gestures induces an alienation Nono did not feel for himself. There is even a quotation from a song by Ockeghem towards the end, as if he was coming to a private accommodation with the history of music and his place in it. Especially in the pieces of Nono’s last decade – La Lontananza Nostalgica Utopica Futura being another fine example of his solo-violin writing – Marxism never precluded mysticism, nor the pursuit of beauty.

Essential Recordings

Como una ola de fuerza y luz, etc.

DG 4232482

Abbado directing Bavarian Radio forces and Pollini in immersive sound, with Slavka Taskova as a heroically committed soprano.

Prometeo

Stradivarius STR37096 (2CDs)

The Missa solemnis of Nono’s music, a fusion of space, theatre, thought and sound in the tradition of Wagner’s ‘total work of art’.

No hay caminos, hay que caminar, etc.

Naïve MO782132

Excellent, Gielen-led collection (if you can find it) of early, mid-period and late examples of Nono’s orchestral imagination.

Fragmente – Stille, an Diotima

DG 4377202

The LaSalle Quartet on top form, always sensitive to the music behind the notes of Nono’s most confessional work.

Hay que Caminar, Sognando, etc.

Kairos KAI0012512

Valuable collection of Nono’s ‘caminar’ pieces for disparate forces, tracing paths between literature, landscape and music.

Intolleranza 1960

Dreyer Gaido DGCD21030

Man the barricades: this azione teatrale caused a riot at its premiere in Venice. Hard to imagine any music doing that now.