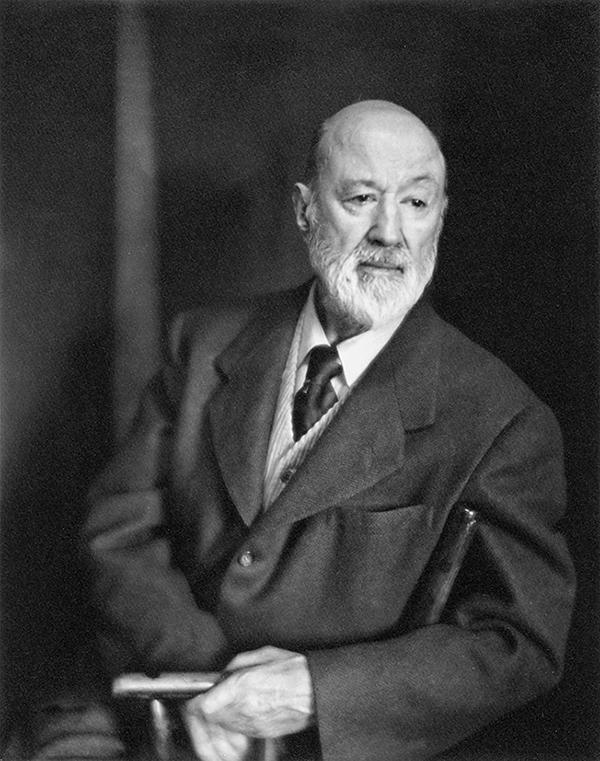

Charles Ives American visionary

Modernist, patriot, man of faith, insurance broker: a new box illuminates one of classical music’s most singular voices, and his recording legacy, explored by Peter Quantrill

It did not take Schoenberg long, after emigrating to the US in 1933, to size up the local scene. ‘There is a great Man living in this Country – a composer. He has solved the problem how to preserve one’s self and to learn. He responds to negligence by contempt. He is not forced to accept praise or blame. His name is Ives.’

Like Beethoven’s deafness, it is worth bearing in mind certain fundamental background factors which do not call attention to themselves when listening to the music. At least in adulthood, Ives never wrote for money. He had no need to. Once graduated from Yale (in 1898) and the solid but limited guidance of Horatio Parker, Ives went into insurance, and revolutionised the industry over the next 20 years with innovative solutions to estate planning.

Down with ‘nice ladies’

So Ives composed not as a hobby, but as a self-supported vocation, like Mahler in this regard. Even more than most composers, the first and only pair of ears he had to please was his own. If others liked what he wrote, all well and good. He could afford to be caustic about his critics, and he was, in a tone of emasculating scorn calling them ‘aunties’ and ‘nice ladies’.

Above: Ives and his wife, Harmony, who later established annual ‘Charles Ives Prize’ scholarships with the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The telescoped nature of Charles Ives’ output as a composer is a second important factor. He was born in 1874 (in Danbury, Connecticut) and died in 1954; almost all his music emerged in a three-decade period between the Variations On ‘America’ from 1891 and Symphony No.4, which was completed around 1923. Ives then lived the second half of his life in a prolonged dusk and then twilight – not unlike his contemporary Sibelius, but occasioned by both physical and mental decline, centring on a case of diabetes.

Something for everyone

Very much unlike Sibelius, this dusk left the Fourth Symphony and Concord Sonata, his two late defining masterpieces, in a state of provisional completeness from which they had to be rescued by other sympathetic hands. It might be tempting to take a postmodernist perspective and say that in this way his aesthetic embodies certain modernist tenets of fracture and rebellion. But Ives would have given the notion short shrift.

More than most composers – Beethoven being the exemplar in this regard – there is something for everyone in Ives’ work. The sacred choral music is largely the work of his lively but pious teenage years as a church organist. The songs are where we find Ives the melodist, in the home-on-the-range tradition of Stephen Foster, and where his contested place in relation to the European classical tradition comes into sharpest focus, in settings of Romantic German poetry.

Ives later compiled 114 of his songs as an autobiographical collection, initially intending to order them chronologically, newest first. Then at the last minute he jumbled them up, in order to alarm and irritate the ‘nice ladies’ who might sit at the piano and sing through a dreamy Romantic lyric such as Feldeinsamkeit or The Housatonic At Stockbridge, then turn the page and find themselves confronted with the experimental expressionism of Thoreau or 1, 2, 3.

Perhaps less familiar than the four symphonies, Ives’ four violin sonatas also chart his musical journey to the outer reaches of tonal language and then beyond, a journey he took parallel to but independent from Schoenberg. No 2 has a barn dance, No 4 shows children at play: Ives’ music is rooted in place and time as much as it is inspired by American Transcendentalist literature of writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, translated into notes in the unavoidable monster of piano literature that is the Concord Sonata.

Hooked on Ives

YouTube hosts an hour-long film of the Fourth Symphony’s belated complete premiere, led by Stokowski in 1965. It features the Columbia producer John McClure talking about the initial impact of the music, through John Kirkpatrick’s first recording of the Concord Sonata, ‘like a first shot of heroin’. Not long after that premiere, McClure determined to record every note of Ives, many of them for the first time. The fruits of his labour have finally been compiled in a new box from Sony, which heads our list of Essential Recordings [below].

Above: Baritone Gerald Finley, joined by pianist Julius Drake, recorded 31 of Ives’ songs at All Saints’ Church in 2004 for Hyperion

Well before Stravinsky, Ives was writing music in two (or more) keys at once. This technique lends pieces such as the first of his Three Places in New England their unique tension between tonal security and slippage. Likewise, when two familiar tunes or rhythms combine and collide, funny things happen, such as No 2 of the Three Places.

Different times

The reception of Ives could have been very different if the dying Mahler had been able to make good on his promise to conduct the Third Symphony in Europe. Instead, it took McClure and American musicians of the stereo generation, such as Bernstein and Tilson Thomas, to give Ives his due as more than a (highly regarded) insurance executive. The music lacks a performing tradition in the mould of Mahler or Stravinsky. Even his best-known piece, The Unanswered Question, can sound completely different across recorded versions that vary in length between 4’38” and 9’16”.

All these themes come together in the Fourth Symphony, which is the ‘everything piece’ to stand alongside the Concord Sonata in his output. The hymns and the marching bands of his childhood, the memories and literature of his mind, the polytonal and polyrhythmic textures, all combine to ask, in the composer’s words, ‘the searching questions of What? and Why? which the spirit of man asks of life... something to do with the reality of existence and its religious experience’.

Nowhere left to go

The Fourth’s third-movement fugue seems to belong to an earlier, more innocent age – and in a sense it does, as an expansion of part of his First String Quartet, written while he was still a student at Yale University. Every period and aspect of Ives’ work is connected to the others, however superficially disparate they appear. It may be that, health and confidence notwithstanding, Ives had written himself out in the Fourth, just as Sibelius did in the Seventh and Tapiola. Simply put, they had nowhere left to go.

Above: The RCA and Columbia Album Anthology from Sony: almost all the Charles Ives you’ll ever need across 22 CDs

Modern recordings of the Fourth, led by Litton [Hyperion] and Dudamel [Deutsche Grammophon] attain a new degree of musical and technical clarity, not least thanks to editors who have continued to work out what Ives had in mind from the unholy mess of the manuscript. Ives’ terrible handwriting had originally forced him out of the junior actuarial department and into client meetings. His music can be messy, too, but in its sincerity, the directness of its transfer from idea to sound, is all the more true to life.

Essential Recordings

The Album Anthology 1945-1976

Sony 19658885962 (22CD)

From Kirkpatrick’s Concord to Bernstein’s Second, this is a trove of classic albums with original jacket covers and good annotation.

Symphonies, Orchestral Sets

Sony 19439788332 (4CD)

Michael Tilson Thomas leads the CSO, SFSO and RCOA in all the major orchestral music. Expansive but detailed digital-era sound.

Concord Sonata

Avie AV2678

Donald Berman – master Ives scholar as well as pianist – pours a life’s work of insight into a patient and far-sighted studio account.

Songs

Hyperion CDA67516

The first of two invaluable surveys of Ives undertaken by Gerald Finley and Julius Drake. Superb diction and a fine sense of fun.

Violin Sonatas

Deutsche Grammophon 4779435

Hilary Hahn and Valentina Lisitsa have the measure of the folksy-modernist idiom. Close-up studio sound, authentically ‘domestic’.

Psalms

Hänssler CD93224

The SWR Vokalensemble under Marcus Creed illuminate Ives’ church-organist past. Unrivalled for completeness and precision.