Schoenberg String Quartet No 2

There are pieces where you can hear the world - of music, of art, of human history - turning on its axis. Arnold Schoenberg's Second Quartet is one of those pieces. At the premiere in December 1908, one newspaper critic sensed and feared this (r)evolution in sound, saying it was 'like a convocation of all the neighbourhood cats'.

If historical significance was all that distinguished the Second Quartet, or musical autobiography, or the notoriety attached to its premiere, then it would be worth reading about, rather than listening to. But the work has much more to offer. He stages, in compressed but real time, the turbulent recent history of music, its painful present and a tentative vision of its future.

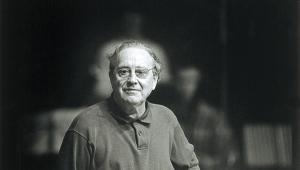

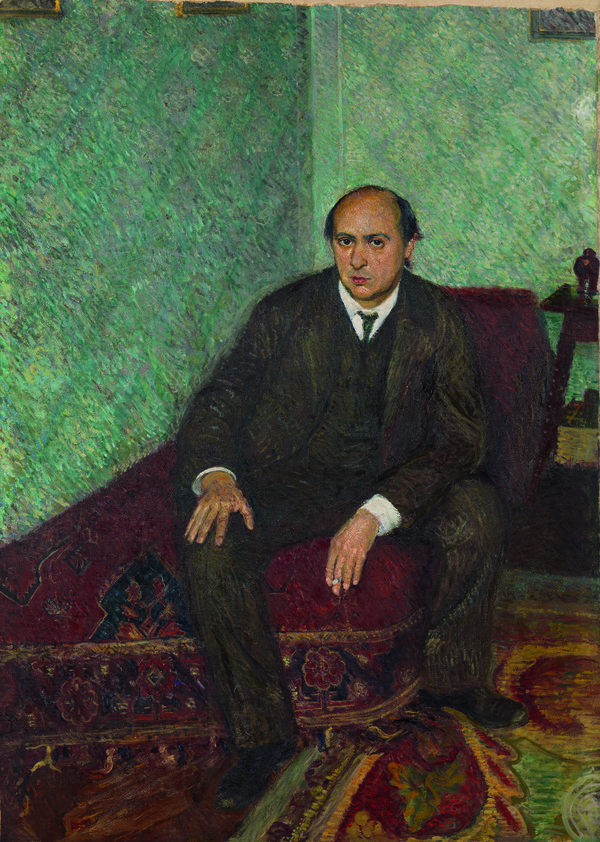

Portrait

painting

of Schoenberg in

1906 by Richard

Gerstl (lover

of Mathilde

Schoenberg)

Break-Up Artist

Schoenberg began composing it in March 1907. In works such as Verklärte Nacht and Part I of Gurrelieder, he had stretched (but not broken) the envelope of Romantic form and harmony inherited principally from Brahms and Wagner. This is how the Second Quartet opens, in a wistful picture of a summer's day, soon giving way to declarations of passion. Dissonant climaxes yield to resolution.

As an excellent cellist, Schoenberg was familiar with Haydn's quartet writing, and it shows, in the harmonious balance of sharing of melody and accompaniment between the four voices. But the first movement's ending is provisional, and the Scherzo starts in a mood of nervous tension - something repressed must break out. A quote from an old Austrian folksong pops up: 'Oh, dear Augustin, it's all over'.

At around this time, Schoenberg discovered that his wife Mathilde was engaged in an affair with the painter Richard Gerstl. He had invited Gerstl to come to his house and teach them painting two years earlier. Now, he insisted that Mathilde break off the affair and return to him. Distraught, Gerstl killed himself soon after.

Like Beethoven and Mahler before him in their symphonies, Schoenberg moved from instrumental to vocal expression in order to access a deeper, or higher realm of feeling. The third movement sets a poem by Stefan George, 'Litainei'. It begins by referring back to the Quartet's opening melody, but the harmony soon folds over on itself to match the text: 'Deep is the sadness that comes over me... Kill the longing, close the wound!'.

With this Parsifalian cry, all the bonds of tonality are broken (motifs from Wagner's final opera make their presence felt in all the previous movements). The Quartet takes off like a hot-air balloon, free of its moorings. 'I breathe the air of another planet', sings the soprano, in a setting of another George poem, 'Entrückung' (Rapture).

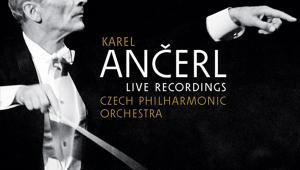

The

Gringolts

Quartet, led by

Ilya Gringolts

(far left) on BIS,

present the

Second within

an outstanding

cycle of the four

quartets

Release Notes

Here, for the first time, Schoenberg composes in the '12-tone system'. What is more striking, though, is that freedom from tonality brings not desolation or angst, but peace. And Schoenberg finally reconciles the two polar forces in a radiant major-key ending.

Never has 'abstract' music been less abstract. Schoenberg could have subtitled his Quartet 'From My Life', if only Smetana hadn't got there first (Schoenberg was an unlikely admirer of Smetana's late Second Quartet, which he regarded as prophetic). He put it this way to his fellow-composer Ferruccio Busoni: 'I strive for complete liberation from all forms from all symbols of cohesion and logic... [Music] should be an expression of feeling, as our feelings which bring us in contact with our unconscious [unserem Unbewußten], really are, and no false child of feelings and conscious logic'.

I think part of the reason why Schoenberg unsettles many listeners - not just the Second Quartet - is because they can sense at an unconscious level that this music does indeed feel not too little but almost too much. The 12-tone system is associated with dry formulas but in practice it liberated Schoenberg and his colleagues to write what they really felt, just as Kandinsky was using new techniques to paint what he really saw.

In coming to know - and love - the Second Quartet, modern listeners have several avenues of investigation open to them. Foremost, I think, is the 1930s private recording made by the Kolisch Quartet. Rudolf Kolisch and his colleagues could count Schoenberg as a friend. The Music & Arts remastering [MACD1056] comes with a touching little thank you from Schoenberg himself. 'One knows affection cannot be expected at a first acquaintance', he says. 'Now everyone, including myself, can hear it in a perfect manner.'

Kolisch and his colleagues play with a warmth and freedom that make specialist-modern ensembles sound chilly and brittle in this music. Unfortunately the soprano, Clemence Gifford, is less sure than her colleagues of either the notes or their expression. Hardly less enlightening, though, are the arrangements of the Second Quartet made (with Schoenberg's approval) for string orchestra. While heavy and over-stated performances may blur the harmony, and produce a curious sequel to Verklärte Nacht, the orchestration also underscores Schoenberg's intrinsic romanticism. Elgar's Serenade for Strings is not so far away, either in style or in time.

Many older listeners came to know the chamber music of Schoenberg, Berg and Webern through the DG set played by the LaSalle Quartet. They now sound quite hasty and business-like in the first movement. The Juilliard Quartet [CBS/Sony] made a landmark early recording, but this, too, is solemn and rhythmically inflexible, like a last will and testament, everything in its place. Better that, though, than the wobbly tuning and desiccated tone of the New Vienna Quartet [Philips].

Top Choice

It is also possible to overdo the modern recourse to authentic rubato and portamento. All the swells and slides quickly become distracting in versions by the Kairos Quartet [Zeitklang], and Fred Sherry and his colleagues [Naxos]. The modern versions in our Essential Recordings [below] are full of their ensembles' collective identity, but they don't lay the Viennese cream on too thickly: the expression is already scored deeply into the notes.

Pressed for a top choice, I find that the Gringolts Quartet strike a balance between analytic clarity and spontaneous feeling which eludes most of their colleagues. There is a bracing, Haydnesque vigour to the rhythms of their Scherzo which places Schoenberg where he belongs, deep in the Austro-German tradition. 'Litanei' reaches the most searing apex of all 'pure' quartet versions, with Malin Hartelius articulating its climactic plunge like a true Kundry. In the alien beauty of their 'Entrückung', one understands why the first audience rioted. They really had heard nothing like it.