György Ligeti: 2001 and beyond

Kylwiria is a beautiful, unknown land with rivers, mountains and lakes, a fairytale place where people live together in harmony. It has its own language, its own grammar. But Kylwiria does not really exist. At least, it existed only in the imagination of a Hungarian teenager, born in a small town in Transylvania in 1923.

Web Design

Dicsöszentmárton, today called Tîrnăveni, belonged to Hungary until the end of the First World War, but was then annexed by Romania. György Ligeti (1923-2006) grew up there with his Jewish-Hungarian parents and initially did not speak a word of Romanian. Because of this, and because his parents were not practising Jews, their son was somewhat isolated from his immediate environment. Ligeti was a loner as a child and spent a lot of time reading and dreaming.

Kylwiria was one imaginary world; another was a nightmare vision of a dusty attic filled with old clocks and spider-webs. Both worlds came to pass in music which defined, developed and yet rebelled from the radical modernism of the postwar European avant-garde. Through the 1960s the composer evolved a style in which he abandoned music written in barlines, melodies and conventional forms. 'Music should not be normal, well-bred, with its tie all neat', he said.

In this respect, his first two orchestral works, Apparitions and Atmosphères, are his most radical. The inner movement of Atmosphères is polyphonic, but the impression on both the page and the ear is of a mass of coagulating lines, 'something like a very densely woven cobweb' – or the imperceptible movement of clouds, within themselves and across the sky.

Space Case

Once Kubrick had appropriated it for the soundtrack of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Atmosphères defined the sound of outer space, just as 'Neptune' did half a century earlier, and in retrospect it seems incredible that Ligeti did not know Holst's score (but true all the same). Imagine his surprise when he took his seat in the cinema, one day in the summer of '68, and heard his own music coming back at him, and not just a snippet or two but long stretches of it. He took the producers to court, and won.

Naughty Boy

Ligeti borrowed Clocks And Clouds as the title of a piece from an essay by the philosopher Karl Popper, but makers of films and festivals have recycled it to bring his music to new audiences. As a metaphor, it holds its value. An entirely new listener to Ligeti should scour the net for Leslie Megahey's BBC documentary portrait, All Clouds Are Clocks. Physically, Ligeti fulfils all the mad-composer archetypes. Spliced between his candid accounts of his past and his ideas, Tom and Jerry are seen racing around to the Ten Bagatelles for Winds and a Proms audience corpses as a tea-tray is smashed in the middle of Aventures.

In Kylwiria, and then in the adult composer's hunger to discover new musical worlds, there are irresistible (and again surely accidental) echoes of Duke Bluebeard's domain. As a student in Budapest alongside György Kurtág, Ligeti had inevitably drawn deep from the well of Bartók's music, producing pieces such as Musica Ricercata for piano.

He later disavowed the work and even later reluctantly reclaimed it once he was content to allow the world to satisfy its curiosity as to his early steps, and mis-steps. The First Quartet is now a repertoire piece, but as the composer remarked: 'My first steps to the real Ligeti music followed after finishing this quartet'.

Ligeti had fled his native country during the Hungarian uprising of 1956. He fetched up in Cologne on the doorstep of Stockhausen, who took him in for a few months. However, he had a Groucho-like resistance to membership of any club. Having won naughty-boy cred with his Poème Symphonique for 100 metronomes, immediately following Atmosphères, he went on to lose it again with the Debussyan sensuality of Clocks and Clouds and the minimalist sequences that make up his Self-portrait with Reich and Riley for two pianos.

Drum Break

At the beginning of the 20th century, Debussy, Mahler and others had found new ideas in the Japanese and Chinese cultures brought to their doorstep. John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen took inspiration from the same in the '60s. Ligeti and Reich looked south, to the central African drumming patterns in which they detected fascinating arrangements and tensions between symmetry (clocks) and asymmetry (clouds).

The music of Adès or Abrahamsen is unimaginable without the example, the techniques and the inventions of Ligeti. But if his own music were merely 'influential', its time would have come and gone. The teeming bustle of San Francisco Polyphony, the comic-strip craziness of his Brueghellesque opera Le Grand Macabre, the yearning lyricism of the Horn Trio and the super-Lisztian keyboard sorcery of the Devil's Staircase study – these are all rich and self-contained inner worlds. And they're as detailed and enticing as any realm in Bluebeard's kingdom.

They are also pieces that draw in performers to measure up to their standards, written at the edge of the possible but rarely beyond it. No choir, however accomplished, can precisely articulate each infernally tangled strand of polyphony in the Kyrie of the Requiem, but the effort to do so is the point.

Fruit Ninja

As a coach of his performers, Ligeti could be sadistically demanding, but he wrote music that embraces fallibility and rewards a strong recreative imagination, nowhere more so than later pieces such as the piano Etudes. Tetzlaff, Kopatchinskaja and Hadelich have likewise made the Violin Concerto their own piece.

The Kyrie is one of many unique Ligeti moments that I treasure. Here are a few others: the bottom dropping out of Atmosphères (3m 20s in the early Rosbaud-conducted version); the fruit-machine pay-out chord in Continuum (1m 37s in the unsurpassed first recording by Swiss harpsichordist Antoinette Vischer); a doleful quartet of ocarinas haunting the aria of the Violin Concerto.

Most of all, there's the entry of the pedal late in the finale of the Second Quartet, marking a kind of homecoming after the weird and wonderful events of the previous 20 minutes. Like Mozart, such moments resist sad/happy-face emojis. They are funny, absurd, sublime and human, all at the same time.

Essential Recordings

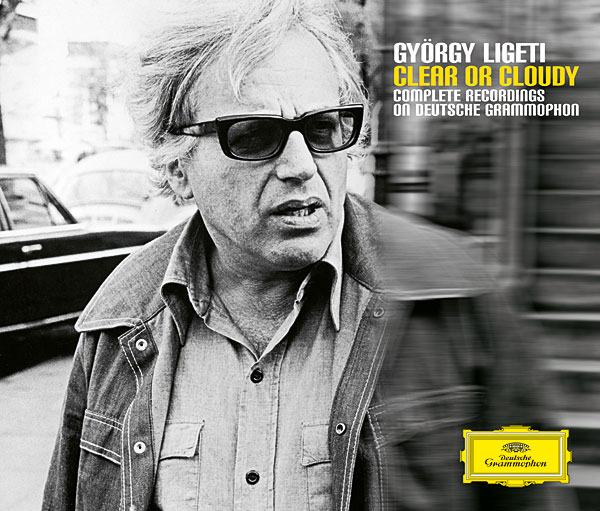

'Clear or Cloudy' – Complete DG Recordings

DG 4776443 (4CD)

Issued after Ligeti's death in 2006, 30 years of dedicated Ligeti interpreters from the LaSalle Quartet to Pierre Boulez.

The Ligeti Project

Teldec/Warner 2564602858 (5CD)

More comprehensive orchestrally, made with the composer's approval, featuring the Berlin PO and the Asko/Schönberg Ensembles.

Masterworks

Sony 190758779225 (9CD)

The other major digital-era edition, now deleted but easy to find, including Aimard in the Etudes and Salonen in Le Grand Macabre.

Violin Concerto/Lontano/Atmosphères, etc

Ondine ODE1213-2

The best single-CD sampler of Ligeti's world. Finnish-made versions of early and late classics in detailed, atmospheric sound.

Continuum/Bagatelles/Volumina, etc

Wergo WER60161-50

Pioneering accounts of mid-period instrumental masterpieces from interpreters who worked closely with the composer.

Complete Études

Hyperion CDA68286

Inspired as well as virtuosic playing from Danny Driver in these new canon works for the piano, celebrating their challenges.