Pablo Casals: Cellist, Conductor, Catalan

Fifty years after his death, it is worth remembering that Pablo Casals was the first celebrity cellist of the modern age. What Paganini had done for the violin, and then Clara Schumann and Liszt for the piano – making a viable career out of touring as a solo virtuoso, as singers had done – it took Casals until the turn of the 19th-20th century. Yet he commissioned very little for his instrument, and then abruptly ceased that solo career at its zenith.

Radical Or Romantic?

Casals was born on the 29th of December 1876 in El Vendrell in Catalonia, where his father was a parish choirmaster and organist. He taught Pablo singing, piano, violin, organ and theory, and made his six-year-old son a box cello. Five years later, hearing a full-scale cello for the first time, Casals found his vocation. He pursued studies in Paris, and by the age of 22 was entertaining Queen Victoria at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

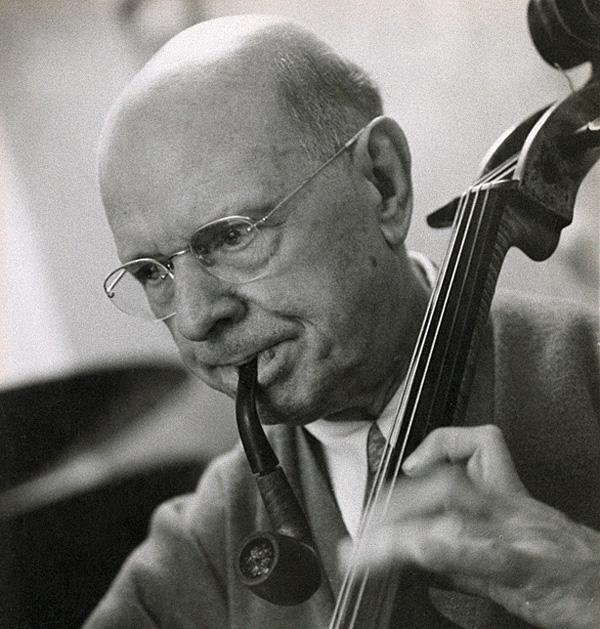

The absence of smoothly engineered stereo recordings from his discography has exaggerated sentimental impressions of Casals as an artist from a lost era. He was more of a radical than a Romantic, in his playing as well as his philosophy. Paul Tortelier remarked that Casals was probably the first cellist to use his left hand in the style of a pianist: 'that is, by normally placing only one finger on the string at a time rather than keeping all fingers clamped down. This allowed the fingers to vibrate freely'.

Now little known but from the same generation, the Hungarian-born cellist Stephen De'ak observed what an ascetic figure Pablo Casals cut on the podium, playing with eyes closed, as the antithesis of the flamboyant 19th-century virtuoso. 'Audiences immediately sensed the fresh musical experience, which was both a leap into the new century, and a reinterpretation of the old'.

No composer embodies that tension between the centuries more than Elgar, and no recording of the Cello Concerto captures its edgy, Edwardian expression of forthright reserve and nervous insecurity more than Casals on HMV in 1945. Not least because of Boult's electrifying presence on the podium it is my favourite Casals concerto recording, ahead by a nose of the Dvořák recorded in Prague and conducted by Szell in 1937.

Both recordings were highlights of the 'Complete Published EMI Recordings' 9CD box released in 2009 and due for reissue by Warner Classics later in 2023, but they can be found in up-to-date remasterings on single-CD Naxos albums. Sony will surely also package up its many post-war recordings, mostly made live in Perpignan and Prades, which last appeared in a 10CD 'Original Jacket Collection' box set.

Golden Decades

Casals had spent much of the war writing a Christmas oratorio to a text by Juan Alavedra. He had intended it to celebrate the eventual arrival of peace but, as he said: 'The triumph of the Allies came, but my country was not freed… and the Peace was only relative'. El Pessebre ('The Crib') waited until 1960 for its premiere, given in Acapulco in Mexcico, where many exiles cast out by Franco and the Spanish Civil War had found refuge. Casals toured with El Pessebre in his last years as a worldwide ambassador for peace, and donated his fee from the concerts to charities.

Cynicism is easy, and the piece itself is hardly the work of a full-time composer, but its simplicity and disarming charm shouldn't be confused for naivety: Casals was too good a musician and too strong a personality to write a dull bar. His cello pieces belong in style to the Catalonia and Paris of his education: lyrical miniatures exemplified by the Cant des ocells (Song of the birds – a free arrangement of a Catalan folksong) which continues to cast a spell as an encore.

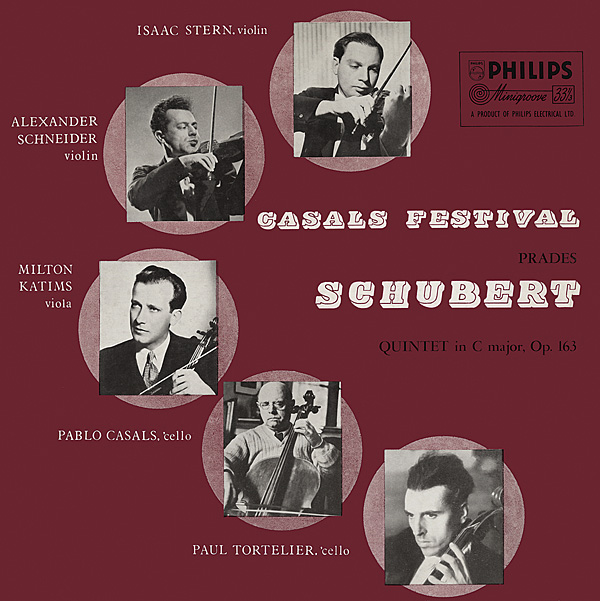

Defying cynicism is the central decision of Casals's maturity, to leave off performing in any country he saw as sympathetic to the Franco regime. This determination effectively sealed off his career as a performing and recording artist in the stereo era. In premature retirement in the Pyreneean town of Prades, he received a proposal from two erstwhile colleagues, Alexander Schneider and Mieczysław Horszowski: 'You can't condemn your art to silence. Since you don't want to leave Prades, we shall come there, in order to celebrate the bicentenary of Bach's death'.

And so in 1950 the festival was born, and with it the golden decades of Casals's career. There followed similar ventures over the border in Perpignan and then in San Juan, the Puerto Rican hometown of his mother, where the cellist spent his own last years before his death in 1976, outliving the hated Franco by a year. 'The love of one's country is a natural thing', he once said. 'But why should love stop at the border? We are all leaves of a tree, and the tree is humanity.'

Out Of The Spotlight

The company of friends brings the best out of Casals the cellist. Every one of the piano-trio recordings made with Thibaud on violin and Cortot at the piano deserves definitive status; their personalities are so distinct yet complementary. The cello so often comes off third best in piano trios – never with Casals. His charisma seems to inspire colleagues without dominating them in Schubert's String Quintet, especially in the Philips-recorded version with the Végh Quartet.

Every Note Speaks

Though Casals apparently led a Granados opera as a teenager, his conducting perhaps relies more on that charisma than technique. Schubert symphonies and Bach concertos demand a degree of indulgence as 'historical' artefacts the way his cello playing never does. Even so, it takes a stonier heart or more rigorous ear than mine to resist him accompanying Maria Stader in Bach's Wedding Cantata, or de los Angeles in 'Zeffiretti lusinghieri' from Mozart's Idomeneo. Look out an INA Memoire Vive album for another sublime example of Casals as complicit musical partner, for Grumiaux in Mozart and Horszowski in Beethoven concertos, where every note speaks.

His technique also remained remarkably secure at an age when the fingers lose their focus and agility. The Third Suite of Bach finds Casals on far more alive and improvisatory form in Prades than the studio version for HMV 30 years earlier. There's nothing of the grand old man about the trios and sonatas recorded by Philips at the 1958 Beethoven Festival in Bonn save for the surely drawn lines and unrestrained frankness of a musician with nothing left to prove.

Essential Recordings

Bach: Cello Suites

Warner 0852902 (2CDs), 9029561926 (3LPs)

The Bach recording that restored a cornerstone of his output, especially warm and vivid in the latest remastering for LP.

The Philips Legacy

Eloquence 4842348 (7CDs)

A new anniversary tribute of late recordings, both live and studio-made, including a stunning unknown Schubert Quintet.

Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert: Piano Trios

Naxos 8110188

All the Thibaud/Casals/Cortot albums deserve their legendary status but the Schubert B flat Trio is an instant tonic for dark moods.

Casals Festivals at Prades

Music & Arts MACD1113 (13CDs) '1187 (12CDs)

Countless treasures from the cellist and friends in two unmissable boxes: off-the-cuff performances, rough-and-ready engineering.

Casals: Works for cello and piano

Klassic Cat KC1014

The best modern collection of Casals's music for his own instrument, featuring cellist Peter Schmidt and pianist Katia Michel.

Casals: El Pessebre

Naïve V4866 (2CDs)

Casals's oratorio for peace, well-engineered and infused with native affection and feeling for its Catalan character.