Richard Wagner: Parsifal

Iwas not thinking of the Saviour when I was composing Parsifal', wrote Richard Wagner to his wife Cosima – dismantling one of many misconceptions held about his last music drama. One practical motivation, having contemplated the subject matter for over 30 years, was an inheritance to Cosima and their children which would secure both their financial future and that of the theatre at Bayreuth which he had built to stage the Ring.

Hence his unique designation of the piece as a 'Bühnenweihfestspiel', or 'play to consecrate a stage'. This was fulfilled by its premiere at Bayreuth in July 1882, and the embargo placed on performances elsewhere, honoured until a staging at the Met in New York in 1903.

Faintly Blasphemous

The religious overtone is deliberate but allusive. Parsifal is no more a 'Christian' work of art than the Ring is Norse or Tristan und Isolde is Celtic. Wagner places sacred symbols – the Grail from the Last Supper, the sign of the Cross, the 'Dresden Amen' as a central motif – in the service of his own dramatic purposes. To think otherwise, and treat the piece as a kind of oratorio, is faintly blasphemous in the face of music charged in every scene with the chromatic pain and erotic transcendence of Tristan.

The mysterious but humanistic 'quest' operas of Rimsky-Korsakov (Kitezh), Debussy (Pelléas) and Delius (A Village Romeo and Juliet) are Parsifal's own immediate legacy, though it permeates 20th-century culture and thought, beginning with Thomas Mann's Death In Venice.

Leap Of Faith

Each of the four main characters has their own quest to pursue. Amfortas and Kundry seek redemption. Parsifal and Gurnemanz seek truths. The opera's longest and least examined role is that of Gurnemanz, set at one remove from the Grail brotherhood led by Amfortas as an old servant of the king's father Titurel. Through watching and thinking largely to himself, he investigates Kundry's double life ('Where were you wandering on the day that our lord lost the spear?') and whether Parsifal really is 'the fool made wise through pity' whom Amfortas needs to recover from his wound.

The original costume designs cast Gurnemanz as a John the Baptist figure in Act 3, ready to anoint the returning hero, but the anti-Christian thinking of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer inflects Parsifal's duty with a Buddhist grasp of the opera's central theme of compassion, and when the choir sings 'Redemption to the Redeemer' it is left unclear what kind of community he will lead.

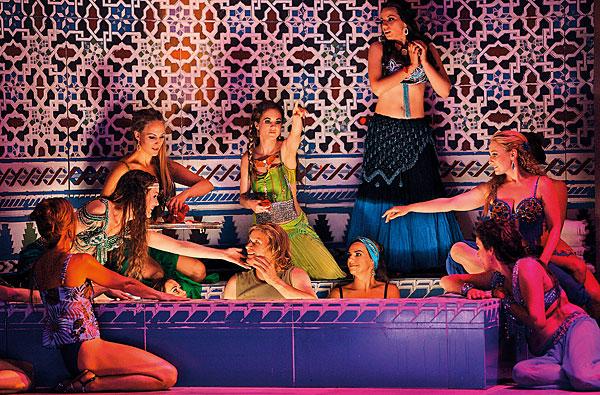

In writing Parsifal, Wagner returned to themes of his own as if trying to heal old wounds or make earlier pieces more perfect. Among them are the rite of baptism prefacing the final scene of Die Meistersinger; the second-act evil sorcerer role of Klingsor channelling Alberich from the Ring and Lohengrin's Ortrud; also in Act 2 the ballet chanté of Klingsor's Flowermaidens, looking back to the Parisian Venusberg scene for Tannhäuser.

The translucent scoring of Parsifal, 'lit from behind' as Debussy termed it, was a further refinement of Wagner's technique and one moulded to the special acoustic of its spiritual home, where the orchestra pit is covered away from the audience and the sound appears more like a glow.

Only a small leap of imaginative faith is required to feel the living presence of both Bayreuth and Wagner in the first extended excerpts from the opera to be set down on record in 1927-8, well remastered on Naxos and led by Karl Muck with the flexible, flowing pulse common to all Wagner conductors of note. For the closest thing to an 'authentic' Parsifal, look up Thomas Hengelbrock's 2013 account on YouTube in decent broadcast sound: essential listening no less than Muck for its unforced, gripping drama and carefully coached, recitative-like cast led by Matthias Goerne's Amfortas.

Having written a thesis on the role of Kundry and conducted the opera for over half a century, Hans Knappertsbusch could draw singing of burning conviction from his cast, even at slow or unpredictable tempi (a new Eloquence box brings together both the live Decca and Philips recordings).

Rituals Of Kitsch

The composer's grandson Wieland had a more radical, 'Latin Wagner' approach and a luminous but sharply contoured sound in mind, embodied first of all by Clemens Krauss (in poor sound for 1953 but electrifying on Andromeda) and then by Pierre Boulez (DG, with rare chemistry between James King's Parsifal and Gwyneth Jones's Kundry).

The cover image of Karajan's 1980 DG set assured it iconic status for a time, but the recorded balance comes and goes, as does Dunja Vejzović's tone as Kundry and the conductor's consideration for his singers. Versions by Goodall, Kubelík and more recently Elder have won a following, but with the exception of Yvonne Minton's fiery Kundry for Kubelík the casts are too often stretched by treating the piece as if it were a High Mass.

Much nonsense is talked about the suitability of Parsifal for concert performance as an 'opera of the mind', perhaps from fear of its power when fully explored on stage. Rather than the ponderous ritual of kitsch served up at the Met by Levine and director Schenk (DG), traditionalists should seek out Sinopoli/Wolfgang Wagner at Bayreuth (DG), slow but probing.

Let There Be Light

Set on and around a huge death-mask of the composer, Syberberg's 1982 film (Filmgalerie 451) still radiates warmth and intelligence from Robert Lloyd's Gurnemanz and Armin Jordan's conducting (and on-screen acting of Amfortas).

Lighting is key to the spell cast by 21st-century stagings in Brussels with Haenchen and Castellucci on Bel Air, and London featuring Pappano and Langridge [see Essential Recordings below]. These respect the ritual and magical aspects of the drama while pointing up the personal nature of the revelations sought and sometimes found by the main characters. Still more radical in his way is Dmitri Tcherniakov in Berlin (Bel Air), backed by Barenboim's beautifully weighted and intimate conducting.

Tomlinson in his prime as Gurnemanz, Leiferkus as Klingsor, Rattle's conducting, Stefan Herheim's Bayreuth staging: all are big omissions from modern records of the opera, but Barenboim both on CD and film works with uniformly fine casts to underscore all the erotic and spiritual ecstasy of Wagner's own final act.