Joaquín Rodrigo: Concierto de Aranjuez

The Concierto de Aranjuez was composed in exile from one war and first performed in the shadow of another. Joaquín Rodrigo began writing it in 1939, having fled to Paris with his wife Victoria from the Spanish Civil War. The couple had met in the French capital a decade earlier, she a recent piano graduate from the Conservatoire and he a student of Paul Dukas at the École Normale. They married in Valencia in January 1933, against her father's wishes, and took a honeymoon in Aranjuez, a town south of Madrid dominated by its royal palace and gardens.

Age Of Elegance

By 1938 Victoria was pregnant, but after seven months delivered a stillborn daughter. Lying ill and in pain, Victoria later recalled, she heard her husband at the piano pick out the melody which would become the focal point of his new concerto: 'an evocation of the happy days of our honeymoon, when we walked in the park at Aranjuez, and at the same time, a love song'.

On a musical level, Rodrigo was mining other memories. Also in 1933 he had composed a Toccata for the guitarist Regino Sainz de la Maza, who performed it on a tour of South America. However, the piece remained unpublished and was only discovered in the guitarist's desk after his death in 1981.

The Toccata's opening three-note flourish becomes the melodic germ of the Concerto's Adagio, now extended with elegiac/erotic overtones that don't (or shouldn't) obscure the fundamentally 18th-century cast of its origins. In writing a guitar concerto, after all, Rodrigo was breaking ground left almost untilled ever since the Classical pleasantries of Mauro Giuliani, the Italian guitar virtuoso who had played cello in the premiere of Beethoven's Seventh but whose own music (not unlike Rodrigo's in this respect) looked backwards to an age of elegance.

The outbreak of the Second World War prompted Joaquín and Victoria to move back to Madrid in 1940. There the Concerto caused a sensation on its premiere given by its dedicatee, Sainz de la Maza, and effectively sealed Rodrigo's career.However, the isolation of the Iberian peninsula from the rest of Europe – political and cultural as well as geographic – is one reason why the piece (and with it Rodrigo's name) was slow to travel. Another was its lack of patronage from the greatest guitarist of the age, Andrés Segovia, who never did pick up the concerto for obscure reasons, none of them reflecting well on Segovia himself.

A third, more practical reason explains why the Concierto de Aranjuez became so familiar – no less than a musical signifier of Spain – through recordings. Guitar concertos do not lend themselves to performance in large concert halls – though the piece hardly fails to make an impact with discreet amplification of the soloist.

A Definitive Pioneer

In 1954 Rodrigo followed up the concerto with his Fantasía para un Gentilhombre – this one expeditiously dedicated to Segovia – but few composers have followed his lead except when prompted by another celebrity guitarist in search of a break from endless tours of Aranjuez. Lennox Berkeley tried his hand for Julian Bream, and more recently Miloš Karadaglić, Jacob Kellermann and Xuefei Yang have commissioned new concertante pieces. With patchy success, it must be said: with Aranjuez, Rodrigo hit the bull's eye first time.

Made by the Spanish label Hispavox in 1948, featuring Sainz de la Maza and masterfully guided by the still-underrated Ataúlfo Argenta, the concerto's first recording should give listeners as well as prospective performers pause for thought. Beginning with at least the sensation of pianissimo rather than an extrovert flourish, the soloist respects both Rodrigo's score and the concerto's arch-like form. The orchestra is audibly chamber-sized, whereas many later recordings employ too large a band, forcing the producer's hand to balance it as a backing soundtrack to the soloist and thus spoiling many moments of intimate and quicksilver byplay in the outer movements.

Sketches Of Spain

Then consider the much-abused Adagio, and not only in its countless arrangements, though jazz listeners should venture beyond its unauthorised use in Sketches Of Spain and try Jim Hall, making magic with Chet Baker on his own Concierto album of 1975. (Rodrigo was furious with Miles Davis and Gil Evans to begin with, before recognising the success of Sketches did no harm to his own name, and coming to a handy arrangement over the album's royalties.)

Sainz de la Maza takes the Adagio in 8m 32s, not rushed but freely rhapsodic, even if the commercial incentive to fit the movement on two 78rpm sides can't be discounted. By contrast, most stereo recordings cast the soloist as a Romantic balladeer for the soundtrack to an unmade essay in cinematic nostalgia. They take more rhythmic liberties, stretch it over 11 minutes and make a Mahlerian apotheosis out of the climactic but neoclassical return of the main theme. Angel and Pepe Romero, John Williams and even the later recordings of Narciso Yepes – they all play a heavy hand.

The most sensitive accounts (nearly all those listed in Essential Recordings, see below) come in between 10m and 10m 30s, and they build the soloist's cadenza as a neo-Bachian accumulation of harmonic tension in the manner of a Brandenburg Concerto. The spiritual brothers to the Concierto de Aranjuez are not Tchaikovsky or film-score rip-offs but Stravinsky's 1938 Dumbarton Oaks and Honegger's Concerto da Camera (1948).

Formality And Feeling

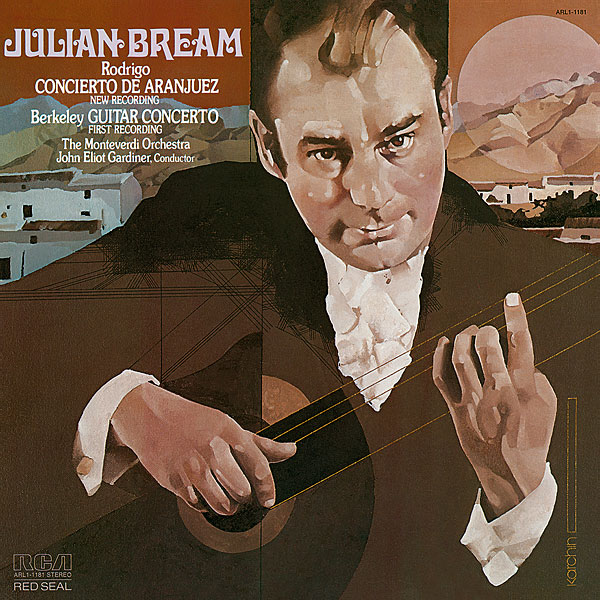

The forgotten gem in the discography is another Hispavox recording, made in 1958 by Renata Tarragó. As creator of the concerto's first authoritative edition she gets under the skin of the work's particular balance between formality and feeling like almost no one else. However, for top-drawer sound and a conductor and ensemble entirely in tune with their soloist, it's impossible to look past Julian Bream, John Eliot Gardiner and his Monteverdi Orchestra of modern instruments but evidently schooled in Baroque practice.

To begin with, I love the clarity of the opening bass pedal beneath Bream's musing invention; the guitaristic imitations of gesture and cross-rhythmic nods to Stravinsky in the orchestra; the deadpan close to both outer movements; and the unforced space and songfulness of the Adagio. More than not putting a foot wrong, Bream and Gardiner get everything right.