Igor Stravinsky: 50th Anniversary

Surely one mark of genius is that even your failures turn out to be successes in the end? The Rite Of Spring's infamous reception at its premiere in Paris in 1913 would have sunk the confidence of a lesser composer. Many of those around him were distraught, while the impresario Serge Diaghilev stoked the flames of scandal. At the centre of it all, Stravinsky kept his head.

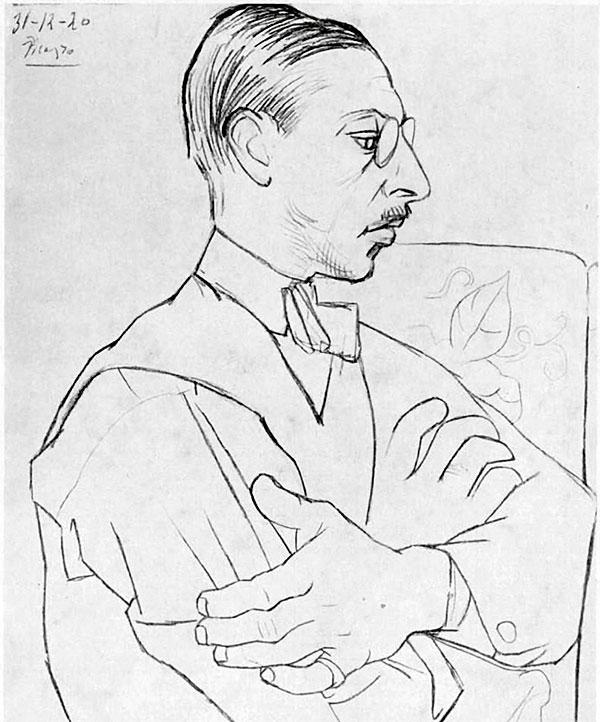

Master At Work

His very earliest works (a muscular Symphony in E flat, a coy little Faun and Shepherdess song-cycle and a newly rediscovered Chant Funèbre) reveal him as an accomplished master, who had outstripped even his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov in orchestration. As his first ballet for Diaghilev, The Firebird is already the work of a master. We can see and hear Stravinsky's gift for making music which is colourful, graphic, witty, but which tells us nothing about the composer himself.

Show, don't tell, we writers are told. What has to be learnt painfully by some composers came as second nature to Stravinsky. He took long-distance lessons from the example of Mozart in Cosí fan tutte when writing his only full-length opera, The Rake's Progress, and framing an immoral comedy within a moral parable. He had Jean Cocteau's libretto for Oedipus Rex back-translated into Latin to distance the story from the listeners, and introduced a narrator to fill us in when the music stops. The paradoxical effect in each case is to screw up the tension and engage our sympathies even further.

The Symphonies Of Wind Instruments are made up of a series of different musical episodes, each cross-cut into the other, resisting the convention of continuity in music. Sometimes the edges of the cuts are joined together by transitions or marked by cadences, but usually they are abrupt, coming at a point where the statement is incomplete.

Unlike chapters, stanzas or even TV shows in this regard, each Stravinskian episode raises the question of 'what happens next?'. They resemble apparently random cuts in the movies of Eisenstein, or perspective shifts in the Cubist paintings of Picasso, to give a sense of different angles from which the observer can form his concept of the whole: showing, not telling.

Vodka-Dry

From his early Paris days onwards, Stravinsky attracted the company of writers, painters and thinkers who found in him a friend, a fellow drinker and also the representative of a new age. Picasso and Giacometti, Cocteau, Eliot and Auden: these and other creators and thinkers recognised the force of inspiration emanating from this small man with the sharp eyes and vodka-dry wit. The same force sprang from him whenever he mounted the rostrum and raised those alarming fists.

Despite Boulez's famous dismissal of him as 'a lousy conductor', Stravinsky not only knew what he wanted, he knew how to get it. Rehearsal footage shows a firm, patient interpreter of his own music, equipped not with a baton or the acid tongue of a martinet such as George Szell, but an armoury of personal charm and wit. That word 'interpreter', though – how he hated it! Stravinsky took pains to decry the idea that a good performer could or should bring anything to a score beyond the skill to bring to life the marks in front of them.

In theory, then, his library of recordings for CBS should retain definitive status. Riccardo Chailly recently told me how any conductor of Stravinsky should study them intently. However, as even the composer came to admit: 'The tempo marks one wrote 40 years ago were contemporary 40 years ago. Time is not alone in affecting tempo – circumstances do too.'

It has been suggested that the Rite Of Spring's opening bassoon solo should be transposed up a semitone every generation or so, to retain its original, fragile quality on the edge of unplayability. We don't have to go that far. With the experience of half a century of making music with the red light on, Stravinsky saw that technology was actually the friend of his music, rather than its enemy. In short, recordings and live performances could achieve complementary, not conflicting, ends.

Later this year, Decca will release a box of Chailly's Stravinsky recordings, made over the last 40 years. In the meanwhile, his latest Rite Of Spring from Lucerne [Decca 4832562] is a demonstration-quality example of how the work's intrinsic violence and primitivism can be enhanced and not compromised by exacting fidelity to the score and ultra-refined execution.

Of conductors from his generation, Sir Simon Rattle and Esa-Pekka Salonen have also produced indispensable Stravinsky collections of their own [see Essential Recordings, opposite], built from the ballets for Diaghilev and neoclassical masterpieces of his 'middle' period.

Fifty years after his death in Venice, however, why not use the anniversary to unlock the door to the often-overlooked room of his late music? The music of the 1960s, from his last ballet Agon to the Requiem Canticles, suffers like late Beethoven from an attitude of intimidated admiration. It's true that the increasingly frail Stravinsky composed as if he had no time or energy to waste. But just as The Rite Of Spring grew from ancient chants and folk songs, Pulcinella from Pergolesi and The Fairy's Kiss from Tchaikovsky, he continued to make new suits from old cloth: Bach, Gesualdo and Renaissance dance.

Pure Music

Stravinsky made new and abstruse 12-tone methods so much his own that it was as if he had invented them; and so he remained, as always, wholly and inimitably himself.

Listening now to Canticum Sacrum, Threni or Abraham And Isaac, one can still hear the composer of the Symphony Of Psalms and Apollo. The five-minute 'Huxley' orchestral variations clear the palette like a 16-year-old Lagavulin: to be sipped and swirled without distraction. In the Requiem Canticles, all 'technique' seems to merge into a world of pure music and transcendent spiritual values.

Collectors on a budget should head to Naxos for the legacy of Robert Craft, Stravinsky's assistant in his later years, who produced performances of more flair and confidence without the composer breathing down his neck. The composer need not have worried that 'interpreters' would get in the way of his music; it continues to demonstrate an imperishable life force of its own.