Sony D-Z555 CD Portable

With full-sized CD players stealing a march on portables in the late 1980s it was left to Sony to step up with a palm-sized marvel of a machine. How would it fare today?

With full-sized CD players stealing a march on portables in the late 1980s it was left to Sony to step up with a palm-sized marvel of a machine. How would it fare today?

The appearance of portable CD players in the mid 1980s presented buyers with something of a dilemma. Should they purchase a full-width model or one of the mobile machines, almost all of which could easily be connected to a full-sized system? A portable would be more versatile, but a large player would be expected to offer more facilities and better sound quality.

The latter point is intriguing, because for many listeners CD was so overwhelmingly better than anything they'd heard before that even the most basic player was a revelation. The thinking in some quarters, therefore, was to buy a portable as it would give you the best of both worlds.

This was good advice to begin with, since the majority of Japanese players in the early days used a single time-shared DAC and offered little in the way of oversampling or similar requirements. All the early portables were built this way too, to save both space and power. As full-sized players improved, a gap opened up. By 1988 all but the most basic of them sported dual DACs and 2x or 4x oversampling digital filters, resulting in an obvious improvement in sound quality. The portable was being left behind but Sony, the first company to market a pocket-sized player, made amends. The D-Z555 seen here was the top model in the 1990 Discman range. It was an incredible achievement, packing all the functionality and performance of a well-specified audiophile player into a palm-sized package.

Super League

As if the ordinary Discman was not enough, Sony had been developing its 'Super Discman' line as a top-of-the-range offering. The D-100 was the original model, followed by the technically similar D-150. Extreme thinness had been the most visibly obvious signature of the series, but by 1989 the situation had improved with the D-250 – essentially a D-150 but with a 4x oversampling digital filter. This brought its performance up to all but the most exacting of hi-fi standards, yet there was one step still to take. This came with the D-Z555, made available in the UK for the first time in September 1989.

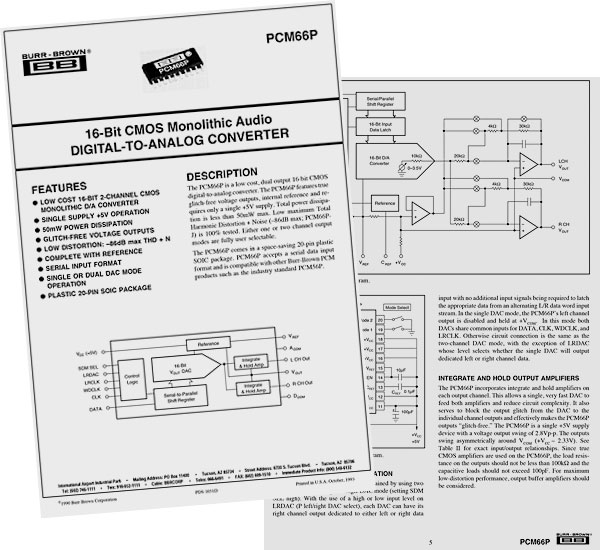

The player's key refinement was the use of dual PCM66P 16-bit DACs with a CXD2551 8x oversampling digital filter, which would have been considered fairly exotic to see in even a full-sized machine. The advanced technology did not stop there though.

Open Tuning

For the first time the user was given access to the parameters with which the digital filter operated, meaning a graphic equaliser, bass-boost function and surround sound mode were all available and enacted in the digital domain. A spectrum display was also included, this too being driven with data taken from the digital filter.

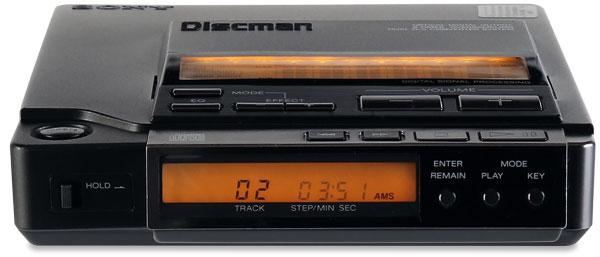

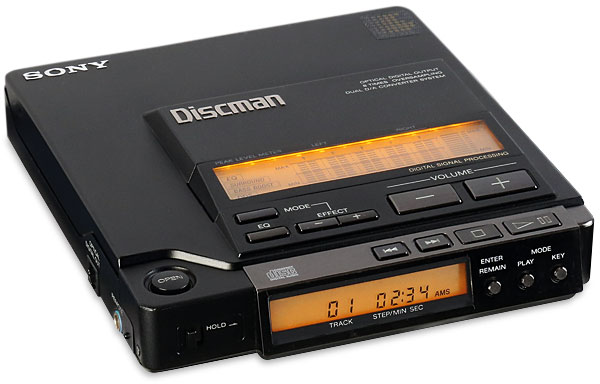

To fit all this in, the idea of a very slim player had to be abandoned – the thicker cabinet accommodating an extra display and controls into its lid, in addition to the traditionally placed ones along its front edge. These were used for both the DSP functions and the volume control, the latter using a pair of up/down keys with a bar graph display to reveal the chosen settings.

The player's tiny cabinet featured other refinements. The headphone and line out sockets were gold-plated, as was the remote control port for some inexplicable reason (both wired and IR handsets were available as optional extras). There was also an optical digital output which was active all the time, regardless of its impact on battery economy.

With both DAT and MiniDisc being some way off there were few components available at the time that could make use of the D-Z555's digital output, but a few amplifiers offered built-in DACs with optical inputs. Whether any of these improved on the generous specification of the D-Z555's built-in digital hardware is unlikely, although their integrated analogue stages might have offered an edge.

Admiring Glances

Compared to some of the Sony portables I've used, the D-Z555 is a bulky, chunky thing, but it feels solid and purposeful too, so its extra size is not something to resent. In the best tradition of Sony ergonomics it looks high tech without being intimidating to operate – the controls you use all the time (play, stop, skip, volume) are large and prominently placed, so it's simple to get the machine up and running. Both displays light up in a soft shade of orange when a disc is playing, and even though the Discman is yet to be rehabilitated as a fashionable cult object in the way the cassette Walkman has, it still looks discreetely desirable and drew many admiring glances while on show in my listening room.

The digital effects work both through the headphone and line outputs and, while they will find little favour with most serious listeners, they still represent one of the earliest examples of such a facility in a consumer audio product. As such they are worth investigating. There are four modes and each can only be used in isolation, not in combination. When adjustments are not being made the four outer bars of the five-bar display show instantaneous and peak-hold level for each channel, the latter refreshed at one second intervals to keep it moving. The graphic equaliser mode offers 20 steps of level adjustment at 63Hz, 250Hz, 1kHz, 4kHz and 10kHz. Such features were standard fare in the 1980s, but to do it all in the digital domain really was something new at the time.

Bucket List

Next up is the surround mode which adds a frequency-selective phase shift and an echo to the sound. Its depth of operation is adjustable, but at all settings bar minimum the effect is unpleasant. It's as if the sound is coming from the bottom of a bucket.