JVC QL-Y66F turntable

In the vinyl heyday of the 1970s and 1980s, differences between UK-designed turntables, and those arriving from Japan, were stark. The suspended subchassis belt-drive decks, popular among British audiophiles, showcased increasing refinement of a ‘traditional’ technology. Japanese corporations, on the other hand, were making use of large research departments and development budgets to produce decks that could correct for off-centre records, direct-drive motors with almost unmeasurable wow and flutter, and control systems with huge torque that would revolutionise DJ-ing.

Arms race

As Japan spearheaded the advancement of LP reproduction during this period, two of its biggest manufacturers were taking a similar route when it came to one method of record replay optimisation. Sony and JVC had already mastered direct-drive motor technology, so concentrated their efforts on tonearm development and, ultimately, came up with ostensibly comparable, and very effective, servo-controlled solutions. Sony’s PS-B80 turntable [HFN Jul ’12] hit the market in 1979 and marked the first outing of its Biotracer tonearm, which would last until the mid-1980s with the PS-X600 and PS-X800 [HFN Jul ’22]. Meanwhile, its rival was capitalising on over 50 years of experience in a similar manner...

JVC had begun in 1927 as the Victor Talking Machine Company of Japan, a subsidiary of the Victor Talking Machine Company of New Jersey, itself founded in 1901. In the years before World War II, Victor was acquired by electronics giant RCA, and JVC subsequently added radios and Japan’s first production television to its manufacturing of phonographs and records. It left its parent company during the war, and in 1953 was taken over by Matsushita Electric, where it was allowed to continue under its own auspices as an independently run operation.

On the ball

When its products were first imported into the UK, JVC was known as Nivico (a contraction of ‘Nippon Victor Corporation’). However, the company’s popularity led to the establishment of JVC UK, an independent entity under the control of Kurt Lowy. This helped the JVC name grow worldwide, while in the UK it became well-known thanks to its sponsorship of both the annual Capital Radio Jazz Parade event and, from 1981-1999, Arsenal FC.

On the vinyl front, JVC had cemented its reputation as a turntable maker by the 1970s. While it is fairly common knowledge that the first ‘modern’ direct drive turntable was the Technics SP-10 of 1969, it’s less widely known that the first unit to employ a ‘Quartz Lock’ speed regulation was Victor’s JB-L1000P professional motor unit of 1974. This preceded Quartz Lock’s first domestic appearances by one year, in the form of JVC’s TT-101 and Technics’ SP-10MkII [HFN Nov ’10].

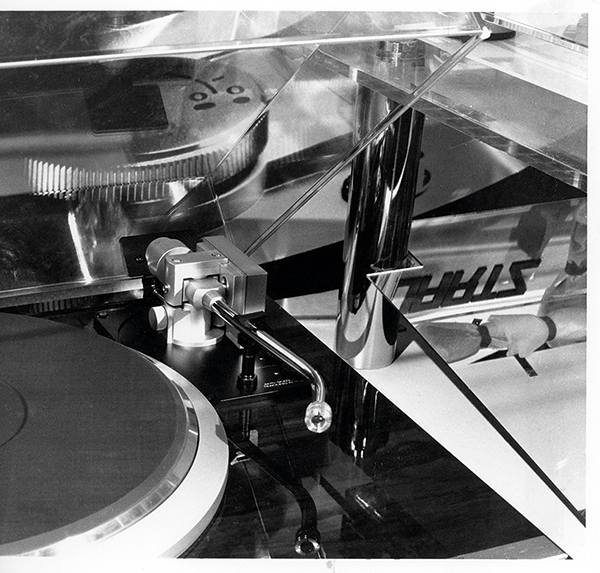

By 1980, however, JVC was ready to unleash the first iteration of its next improvement on record replay: the Electro-Dynamic Servo tonearm. This used two coreless linear motors in the tonearm bearing housing, the aim of which was to minimise resonances arising from imperfect pressings and the reaction of the tonearm mass and cartridge compliance. One motor acted in the horizontal direction and one in the vertical, and both aimed to keep the position of the stylus fixed, regardless of external disturbances.

As described by JVC itself, ‘when the tonearm is pushed upwards by a warp, this causes the magnet for vertical velocity detection to move, generating a corresponding voltage in the associated detection coil. This voltage is amplified and sent to the drive coil of the vertical motor to develop a counterforce in the opposite direction to the original force. This keeps the stylus in close contact with the groove and the entire cycle takes a fraction of a millisecond’.

Second helping

The Electro-Dynamic Servo tonearm debuted in 1980 on the QL-Y5F and QL-Y7F turntables, and in the more affordable QL-Y3F for horizontal control only. However, JVC introduced a second generation of models in 1985, comprising the QL-Y55F, ’66F and ’77F. All were only slightly different stylistically and their essential features were very similar, but it was the QL-Y66F that became the most widely known and popular model.

This turntable features JVC’s coreless DC servo direct-drive motor spinning an oversized 35cm diameter platter, weighing in at 2.9kg, via a precise Quartz Locked control system. The company claimed 0.03% (DIN-wtd) wow and flutter and less than 0.0001% speed drift per hour. Note that some publications quote a W&F figure as low as 0.005%, but bear in mind this was measured using the output signals of the control system, and not the actual platter rotation [see PM’s Lab Report]!

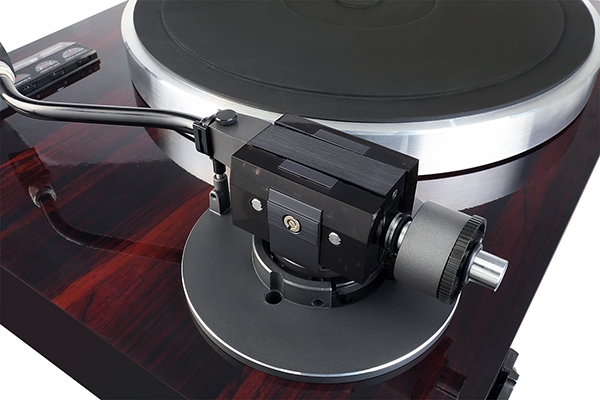

The second generation E-D Servo tonearm utilised plug-in armtubes and the QL-Y66F was supplied with two. One was an S-shaped tube with detachable SME-style headshell for cartridges weighing between 8g and 14g, or 15-21g with a supplementary counterweight. A second, straight armtube with fixed headshell catered for the range of 4.5-10.5g, and 11.5-17.5g with the extra weight. There was also a third option – a straight type with a carbon fibre tube – for ultra-low mass cartridges, but this is incredibly rare.

Smooth operator

The QL-Y66F’s E-D Servo system means that tracking force, bias and damping are all adjustable via controls mounted on the top of the plinth and can even be tweaked ‘on the fly’. The only manual aspect is setting the arm’s zero balance in the conventional manner, using the counterweight once the QL-Y66F’s ‘zero balance’ button has been pressed to disengage the servos.

On the subject of ease of use, JVC’s turntable is fully automatic in operation, utilising a very slinky electronic drive set-up. Oddly, though, both record speed and size have to be set manually – there is no auto-detection of either. There are, however, buttons for arm lift/lower and left and right movement, so there is no need to touch the tonearm itself even when manual cueing is required. A continuous repeat option can also be selected.

Sadly, the development of these innovations coincided with the launch of CD, and so the pesky ‘silver beer mat’ did generally bring turntable development in the Far East to something of a halt, barring a few notable exceptions. The QL-Y66F lived on until 1987 but, following this, JVC’s turntable range was whittled down to a few solid but unremarkable models for ‘basic’ LP replay, serving enthusiasts as they built up a replacement CD collection.

JVC carried on producing some very fine equipment into the 1990s, before its gradual decline led to a merger with Kenwood in 2011. Today the name only exists in the audio market as a logo on headphones, in-car systems and one or two boomboxes, although its 4K projectors are highly regarded by home cinephiles.

![]() Adam listens

Adam listens

It is somewhat bittersweet listening to the QL-Y66F today. Remembering that it wasn’t even JVC’s range-topper, coming in below the QL-Y77F and the QL-A75, it is still something of a surprise to hear just how good a turntable it is. Most obvious is a glorious sweetness, clarity but also a gentle softness across the upper registers.

JVC’s turntable has insight by the bucket load, but doesn’t throw this at you relentlessly. Whether sporting an Ortofon 2M Black MM pick-up [HFN Mar ’11] on the straight armtube, or using a Clearaudio MC Essence MC [HFN Aug ’17] on the S-shaped version, the QL-Y66F gave the distinct impression that it was adding nothing to the music, while taking little away. Both cartridges’ characters were easy to discern without any intrusion from the deck itself.

Of the on-the-fly user adjustments, the most interesting is the arm damping setting. Moving to a turntable without it is like the wrench that occurs when going back to a conventional turntable after hearing the difference made by an ‘off-centre correcting’ Nakamichi TX-1000 [HFN Aug ’16]. With the QL-Y66F, adjusting the damping as the record plays is fascinating. In the case of the Clearaudio MC Essence, it took it from being slightly edgy at ‘0’ through to a little over-damped and flat-sounding at ‘3’. However, passing around 1.7 on the scale seemed to hit the cartridge’s sweet spot.

Once dialled in like this, the QL-Y66F really doesn’t put a foot wrong. In frequency terms it has an impressive uniformity from top to bottom. As mentioned, its handling of higher frequencies is a thing of wonder, adding a lightness of touch and openness to the recorders on Mike Oldfield’s 'Portsmouth', from his 1975 Ommadawn album [Virgin V2043]. Also a delight was the fancy footwork of the Morris dancers in the background, stamping cheerily along in time.

Everything in its place

The QL-Y66F also has no problem in setting up an impressive performance space in terms of both depth and width. It doesn’t send musical elements flying into the far distance but seems to just put everything right where it needs to be. ‘Bird On A Wire’, a favourite demo track from Jennifer Warnes’ beautifully recorded Famous Blue Raincoat set [Impex Records IMP6021], has a well-defined layout of instruments and the better the turntable, the easier they should be located. Through the QL-Y66F, Warnes’ vocal performance was emotive and rock-solid between my loudspeakers, while I could determine exactly where every performer was placed.

Naturally, with a good direct-drive motor at the helm, a fine bass performance is expected and, once again, the QL-Y66F delivered. The synth bass notes on Jamie XX’s ‘Obvs’ from his In Colour LP [Young Turks YTLP122] came across with taut precision and an ominous sense of thunder. Equally, though, the deck added a fine warmth and richness to the double bass backing Rebecca Pidgeon’s version of ‘Spanish Harlem’ from her popular The Raven LP [Chesky Records JR115].

Downsides? Well, the QL-Y66F’s plinth isn’t a back-breaking lump of woodwork and if you’re less than careful with positioning it can make the deck prone to feedback and deaden the bass slightly. However, I would suggest that anyone investing in a turntable like this is unlikely to plonk it on the nearest bookshelf and hope for the best. In other words, a sturdy and solid support is required – make sure you have one, and the QL-Y66F will give of its best. Note that it did not respond well to a damping platform between it and my regular Atacama rack. A solid and massy support works best.

Buying secondhand

The QL-Y66F is not as rare as some other high-end Japanese turntables of its era, and is generally very reliable, although complex and occasional electronic faults are always a risk with anything approaching 40 years old.

The comprehensive service manual remains available online, to help with any woes. There are some application-specific ICs contained within the deck, although they were shared with other models, so a ‘parts’ unit may yield what you require if you do encounter a component failure.

Odd symptoms can be caused by the tracking force, bias and damping controls developing ‘flat spots’ after years of non-use. Consequently, a workout of the controls or a squirt of switch cleaner may be all that is required to bring a unit back into line if it starts misbehaving. Additionally, if any of the buttons are unresponsive, it might be the internals of the button itself crumbling. Replacement is possible, but it’s fiddly and could require a little creative ‘re-modelling’ of a modern item.

One important consideration is whether any QL-Y66F you are looking at is supplied with the armtube you require. While individual armtubes do crop up from time to time at Japanese specialists, you’ll need to budget between £200 and £300 each for the S-shaped or standard straight designs. As to that rare carbon fibre low-mass item, I have only ever seen one for sale and the asking price was £700. Predictably, it was snapped up very quickly.

Hi-Fi News Verdict

The JVC QL-Y66F is another statement turntable from Japan that showed just how easy yet rewarding vinyl replay could be. The deck is a pleasure to use, compatible with a wide range of cartridges and simply gets on with making music without any drama or fuss. I recently read a comment suggesting it was ‘the best fully automatic turntable to come out of Japan’ and, I have to say, I’m struggling to disagree.

Sound Quality: 87%