Wharfedale Linton amplifier

A child of the Rank Organisation, the Linton can trace its roots back to the Leak Delta 30 and Stereo 30 Plus before it. We travel back to Wharfedale’s (early ’70s) halcyon days

A child of the Rank Organisation, the Linton can trace its roots back to the Leak Delta 30 and Stereo 30 Plus before it. We travel back to Wharfedale’s (early ’70s) halcyon days

The Wharfedale Linton loudspeaker is one of those hi-fi products that seems to have been around forever. It has been produced in many forms and is still with us today in ‘Heritage’ guise. The original Linton, Super Linton and Linton 2 were all strong sellers in the 1960s and ’70s and many listeners will have heard, owned or borrowed a pair at some stage. Lesser known was Wharfedale’s complete Linton system, which was offered in hi-fi’s boom years of the early 1970s. It is the amplifier from the first version of this which we are looking at this month.

Privilege of rank

Wharfedale had its origins in the early 1930s but was sold to the Rank Organisation in the late ’50s. Rank already owned Bush Radio at this stage and would acquire Murphy Radio shortly afterwards, giving it an impressive portfolio of consumer electronics. Wharfedale was largely left alone under this arrangement, but things would change at the end of the ’60s when Rank bought Leak. This gave the company access to a popular and well-regarded range of amps and tuners as well as yet more loudspeaker designs. Rank also became the UK distributor for Akai tape recorders from Japan around this time.

To make the most of the Wharfedale name it was decided to offer more than just loudspeakers in the range. The Linton amplifier seen here was introduced in 1973 and was accompanied by a matching turntable and a revised model of Linton loudspeaker, the Linton 2. None of this was especially difficult to do. The Linton turntable was a BSR MP60 deck fitted with a Shure M44 cartridge and mounted in a Wharfedale-designed plinth. The amplifier came from Leak and was based around the then-new Delta 30 model, itself a development of the Stereo 30 Plus [HFN Sep ’20].

The challenge was how to offer essentially the same product twice without upsetting existing loyalists with badge-engineered components and without needlessly creating one’s own competition. The marketing strategy used was to retain Leak’s position as a ‘technical’ brand for the serious enthusiast and position Wharfedale as something more stylish for those who wanted eye-catching, good-sounding equipment. Leak’s Delta 30 amp looked less like a piece of laboratory equipment than the Stereo 30 Plus, but it still had lots of controls and functions, which could confuse the non-technical user.

Lean layout

To simplify operation the Linton was shorn of options to connect a second turntable, a second tuner and a microphone. It also lost the option to play either stereo channel through both loudspeakers (this being replaced by a simple ‘mono’ button) and the headphone socket, which took with it the switch to turn off the loudspeakers. The DIN connector for a tape recorder on the front panel was also deleted. To keep the costs down, the blank holes for the sockets no longer present on the rear were covered by a plate, which better explained how to use those that remained. RCA type connectors were employed for all inputs, with a single pair of DIN sockets used for the speakers. As well as making the Wharfedale Linton less daunting to setup and use, these changes also made it a useful £5 cheaper than the Leak Delta 30.

You’d never have guessed Wharfedale’s amp was the ‘budget’ choice – the top and sides were finished in a choice or real teak or walnut veneer and the fascia was made of beautifully polished aluminium. It looked sleek and modern, especially when used with the Linton turntable that had been carefully styled to match.

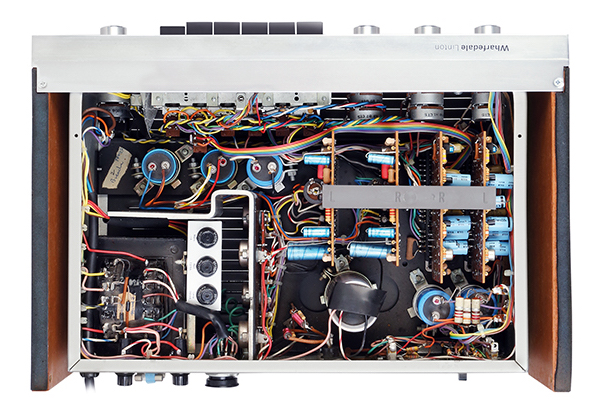

Silicon inside

Inside there had been a gentle evolution from the design of the Leak Stereo 30 Plus. Changes had been confined to minor improvements in component types to either boost performance or reliability. The 2N3055 silicon output transistors remained, however, and the amp was still rated at a leisurely 15W/8ohm [see PM’s Lab report]. The slightly odd preamp arrangements of the Stereo 30 Plus were also carried over, in particular the quirk where the recording outputs were affected by the settings of the treble and bass controls. The phono stage remained in circuit all the time too, even the high-level signals from the tuner and tape machine passing through it. Yet when line inputs are selected this ‘phono preamp’ is switched to a flat, unity gain stage to prevent (overload) distortion.

The Linton amplifier lasted for two seasons before it was replaced by the Linton Mk2. This was a very different design and originated in Japan, possibly as part of a collaboration between Rank and Toshiba over colour TV production in the UK. Wharfedale was never given its own version of the Leak Stereofetic or Delta AM/FM tuner but it did offer a range of receivers, mostly Japanese sourced, for those who needed radio.

Much as I would have liked to have seen (and heard) the Linton system in its entirety, the amplifier was still something of an eye-opener. It really is very pretty and still looks the part, something that would be more difficult to say about the Leak versions. Making the cabinet slightly wider has made the overall proportions more pleasing and the finish is first rate. This is to be expected, for the Linton was not a budget unit when it was new – a B&O Beolab 1700 was slightly cheaper and promised slightly more power, as did the Rogers Ravensbrook [HFN Jan ’16] for only a few extra pounds.

Do the twist

The removal of the potentially baffling connection options of the Leak model makes the Linton really easy to setup, even if the British-pattern RCA connectors are a little too close together and the earthing point for the turntable is some distance from the signal inputs. The best way to use the DIN loudspeaker outputs with modern cables is via a set of adapters – far more preferable to the rear-panel butchery one so often sees where someone has fitted a (wonky) set of 4mm sockets.

This design does not have a stabilised power supply and so it is necessary to set the mains voltage using a carousel type plug at the back. Six options are offered, none of which are marked 240V – the standard when this unit was new. Before leaving the subject of power supplies, it is worth mentioning that the Linton came with a generous 2.8m of captive mains cable – about twice the standard length.

Zero tolerance

The reduction of input options means that those wanting to connect a line level source (CD player, DAC, etc) to this version of the Linton only have the tuner and the tape inputs to choose from. Both offer the same sensitivity (when the tuner input is set to its least sensitive position) but even though there is no audible sign of overload in the low-level stage it is clear that the standard 2V line level is too high for this design. The volume cannot be completely reduced to zero and the action of the control is abrupt with only a small arc of rotation delivering a fair proportion of the available output all at once. External attenuators are available to solve these kinds of problems and are strongly recommended for the Linton.

![]() Tim listens

Tim listens

I have some admiration for the Leak Stereo 30 Plus on which the Linton is based. It doesn’t offer the last word in sound quality but works as well as some of the far more elaborate units of its era while remaining uncomplicated. Leak promoted the original Stereo 30 as an improvement over the earlier (and now highly regarded in certain circles) Stereo 20 and in many real-world listening situations it is easy to see what it meant. In Linton guise the design retains much of its character. It is a willing performer with an even tonal balance and just enough power to generate realistic musical experiences if partnered with reasonably sensitive loudspeakers.

The treble is bright if not particularly extended and bass is warm without being thunderous. An advantage of the unusual placement of the volume control in the circuit is that noise from the preamp is well suppressed at commonly used settings. And there is no noise audible from the listening position when using the line level inputs. Whenever I listen to one of these models I leave with the impression that they don’t sound greatly different to comparable products on sale ten years later. In many ways they are quite ‘modern’.

Saving grace

The amp has its limitations, of course. Vocals can sound slightly defocused or veiled compared to the results obtained from a really top-class amplifier. The effect is a subtle one, but once recognised it can also be heard as a smoothing of texture in voices and a lack of bite in percussion, even when there is clearly enough treble headroom to reproduce these sounds more vividly. It must be understood that this is a minor criticism indeed given the age and the market positioning of the Linton. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate one of the drawbacks of what is, by current standards, a fairly primitive design.

Listening to the Grace Jones album Nightclubbing [Island IMCD 17] showed that the Linton had just about sidestepped the ‘small amplifier’ sound that can limit many a low-powered model. Rather, it presented itself as dynamic and reasonably lively while having no obvious tonal imbalances. Yes, the sound was perhaps a little too dry to enjoy the heavy sound of this album perfectly, but the Linton is far from being alone in this regard.

Take your seatsWhat was disappointing was the two-dimensional nature of the soundstage, which resolutely refused to project itself into the room. Instead, everything was stuck inside a flat rectangle bounded by the corners of the loudspeaker cabinets. Within this space the various voices and instruments were well placed, but nothing ever ventured outside it.

Keen to see if this effect was present in orchestral pieces as well as studio material I also tried a selection of music performed by John Williams and the Boston Pops Orchestra [Philips 432 802-2]. This is very much a ‘front row seat’ type of recording that with good equipment will put you right there – laid-back it certainly is not. The Linton amp blunted the brass a little and took some edge out of the strings, but that was its only real drawback. Even the soundstaging had expanded a little, although it still lacked any real front-to-back depth.

Buying secondhandThe original Linton isn’t a common model but the Japanese-made Linton Mk 2 is, so be sure that any potential purchase is the version you want. The world is full of Leak Stereo 30 Plus and Delta 30 amps though, so the most important part of buying an original Linton is to find one with a cabinet in good condition. The polished fascia is readily scratched and the screen-printed legends are easily rubbed away, so check these first. Also ensure the amp’s rotary knobs are the correct ones and that they are all still present.

Technically you should encounter few difficulties. Most of the circuit is on four plug-in modules that are easily swapped with those from a tatty Leak. The component quality of these later models is better than the earlier ones, so there is no real need to change handfuls of components for the sake of it. Nonetheless, these models are a common target for those who like to indulge in this sort of thing. As ever, prioritise examples that are clean and original.

Hi-Fi News Verdict

Today the Wharfedale Linton amplifier is an excellent first step into hi-fi, just as it was when first released. Durable, simple to fix and able to be found on the pre-cherished market with a little effort, vintage amplifiers don’t come much more painless. What’s more, it’s not too difficult to build a versatile system around it. Some may dismiss the Linton as merely a Leak Delta 30 in a pretty box, but is that such a bad thing?

Sound Quality: 80%