Shostakovich: Symphony No 5

New pieces by composers Harrison Birtwistle or Peter Maxwell Davies, say, will have received polite applause and a few boos from the audience at their premieres. But no government response.

Things were very different in 1930s Soviet Russia under Stalin, when a knock at the door could lead to interrogation – or worse. Composer Dmitri Shostakovich was already in the doghouse after performances of his 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. And completing his Symphony No 4 – a big brute of a work – he withdrew the planned Leningrad premiere in '36, after denunciation by the State. (This was not performed until 1961, during the Kruschev era.)

Whether or not there was coercion, an article in a Nov 1937 Moscow newspaper credited to Shostakovich said the new work, his Symphony No 5, was 'a Soviet artist's creative response to justified criticism'. The premiere that month, on the 21st, was given by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky, who raised the score aloft to tumultuous applause. Party officials claimed that the audience comprised only Shostakovich supporters but, at the same time, that it showed success in 'rehabilitating' the composer, now writing music for people to enjoy.

Years later, it was claimed that the triumphant finale was written with irony in mind – as Krzysztof Urbański says in a video trailer for his NDR Elbphilharmonie Alpha recording, the music is like being repeatedly beaten about the head with the pronouncement 'Your business is rejoicing'. A tragic reflection of the prevalent terror.

A budget 'must have' CD, Vasily Petrenko's 2008 RLPO recording in his Naxos cycle [8.572167] stresses the revised view of that ending too. The coda also has tonic sol-fa coded references to a woman who had spurned him – like the DSCH motif in Symphony No 10.

A year after the premiere, Mravinsky made the first 78rpm recording, Stokowski following at Philadelphia in April 1939. A detailed examination of the Mravinsky is set out at dschjournal.com. And you can still hear the 1942 Rodzinski/Cleveland version with its crazily fast finale, now on Naxos.

My first encounter with the work came via our Ferguson AM radio, which I commandeered nightly to the irritation of my father, looking for classical concerts from foreign stations. It was the eerie Largo, with its concluding celesta, that most profoundly impressed me – slow music the like of which I'd never heard before. The conductor was Leonard Bernstein, with his New York Philharmonic Orchestra, performing in Paris (if I remember correctly).

The Test Of Time

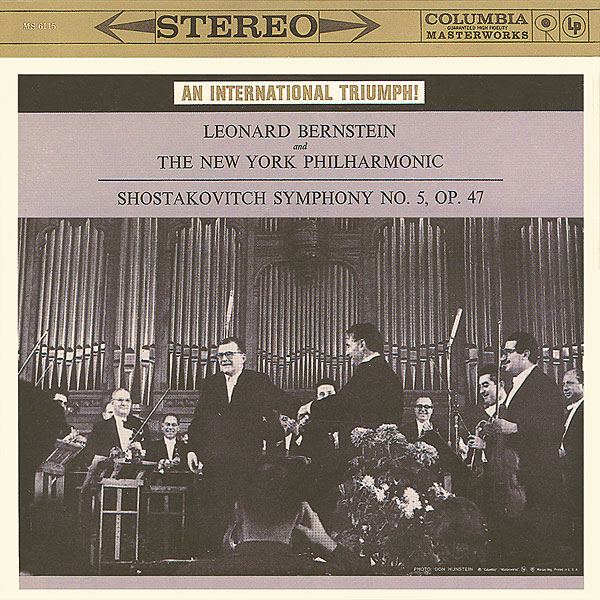

In 1940-41 he'd seen Koussevitzky conduct it at Tanglewood, then did it himself in Boston, Detroit and San Francisco, three years later. He made his first recording in 1945 for RCA Victor. The Symphony was in the repertory for his 1959 NYPO European/Russian tour and recorded promptly on their return to the States (it was made at Boston's Symphony Hall on 20th October, John McClure producing). As the sleeve shows, Shostakovich attended the concert to hear his Symphony No 5 – he and Bernstein were introduced at a 1949 World Peace Conference, along with Aaron Copland (thereby identified as 'commies' by the far right!).

It has stood the test of time, rather overshadowing Eugene Ormandy's no less committed interpretations on the same label. The set I highlighted in Classical Companion [HFN Sept '20] has his 1965 RCA recording, although – exaggerated stereo separation apart – the later one was preferable.

We also had a CBS digital LP [35854] which was recorded in July 1979 by Bernstein/NYPO at two Tokyo concerts. Amazon UK lists the CD reissue as still available [SK94733]. The finale is much broader there, 10m 07s vs. 8m 59s, although the composer is said to have endorsed the earlier approach (Mravinsky's several recorded timings were around 11m.)

In 1966 the BBC televised Bernstein in No 5 with the LSO, an electrifying piece of film, and a Euroarts DVD has remastered this footage adding a short rehearsal excerpt [3081358; b/w, mono].

Engineered by James Lock, the first LSO recording with André Previn [RCA SB6651], along with their Walton No 1, confirmed that as a classical conductor he was to be taken very seriously indeed. This was a landmark release really deserving of a 180g vinyl reissue – or at least a decent high-res download option.

The composer's son Maxim also recorded No 5 with the LSO [now an Alto budget CD], and – in terrible picture quality – there's a YouTube uploaded 1985 Barbican filmed concert performance. At least you can see how like his father he was, the grace of his podium gestures and sense a moving dedication to the score. At 48m 07s it's 4m shorter than Mravinsky live in 1984 [Erato]. EMI issued Maxim's USSR SO/Melodiya LP recording in 1970 and the US had a 1996 RCA CD transfer [74321-32041-2].

Back in 1960 we had a really distinguished No 5 from DG, with Witold Rowicki and the Warsaw NAT PO, albeit in dim stereo sound. As an interpretation, though, it's well worth looking for as a CD [453 9882]. But this 'Galleria' reissue you can only buy as an MP3 download today. Rowicki's LSO/Philips remake was far less interesting.

Free To Choose

Incidentally, Gramophone has a website review by the late Michael Oliver of the second recording by Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, made with the Hallé Orchestra [now transferred to the orchestra's label CDHLD7511]. It's worth reading as a reminder of this perceptive writer.

Needless to say, we've had recordings from all the great Russians, including Ashkenazy, Barshai, Jansons, Kondrashin, Rostropovich (I'd skip his three efforts), Rozhdestvensky, Svetlanov and Temirkanov. Of these, I'd pick the one by Rudolph Barshai, given with the WDR Orchestra [Brilliant Classics 6324;11CDs].

Then there's Kurt Sanderling – an 'honorary' Russian, as he spent from 1942 to '60 working with Mravinsky, and became a personal friend of Shostakovich. His No 5 is with the Berlin SO [Berlin Classics 0300750BC]. I vividly remember a Royal Festival Hall No 8 he conducted many years ago…

Khachaturian once queried Sanderling's opening tempo of (iv) but the composer said 'No – let him play it like that'. 'So, you see,' said the conductor, 'that he was open to various different interpretations of his works. He was not stuck with one tempo or one style.'