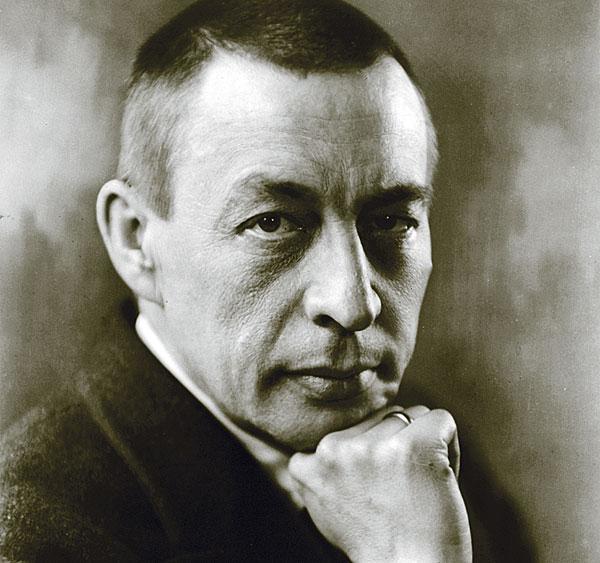

Sergei Rachmaninov (Symphony No 2)

'A six and a half foot scowl' was how Stravinsky defined his fellow compatriot composer (they both left Russia for the States). But there's plenty of historic film which shows this aperçu was wide of the mark. You can see him on the boat crossing the Atlantic, relaxing with family and friends in America, and standing with one of the big cars he enjoyed there [to the accompaniment of the slow movt of Symphony No 2 in the 1959 RCA/Sony Ormandy recording]. But we have no performance material, alas, either as pianist or conductor.

His First Piano Concerto (1891, revised in 1917) was one of his early successes, his First Symphony premiere catastrophic in its effect. It was badly conducted by the composer Glazunov and panned by critics. As a consequence, Rachmaninov sought medical help, including daily hypnotherapy, before his self-confidence returned.

By 1906 Rachmaninov had abandoned two teaching posts and conducting work at the Bolshoi Theatre, to spend three years with his family at Dresden, where he began work on the next symphony. Visiting a Leipzig gallery he saw Böcklin's painting The Isle Of The Dead, which inspired his own composition (he made a piano-roll recording of this and an orchestral 78rpm set for RCA in 1929).

Rachmaninov gave a St Petersburg premiere of his Symphony No 2 on 26th January 1908, dedicating the score to the composer Taneyev (with whom he had studied counterpoint – there's a restless fugue in the second movement Allegro molto). But with an exposition repeat in (i) the playing time was about one hour and interpreters soon started making damaging cuts.

The manuscript score became lost until Telegraph critic and Rachmaninov authority Geoffrey Norris was telephoned from Switzerland: it was shown to him in 2004 for authentication. After an injunction then stopped a planned Sotheby's sale, a decade later it went for £1.2m.

The very first recording (1928) was with the Cleveland Orchestra, under its first principal conductor Kiev-born Nikolai Sokoloff. Three other early versions were made in the States by emigré conductors, but not released here. Claims that the USSR RSO/Alexander Gauk recording, briefly available here in 1958 [Parlophone PMA1038], was the very first uncut version are contradicted by some reviewers, but Paul Kletzki's 1968 Decca stereo LP with the Suisse Romande Orchestra [SXL6342] certainly was uncut.

Leningrad Benchmark

Russian orchestral recordings imported from MK (Melodiya) in the 1950s often deterred collectors both by their inferior engineering and generally noisy surfaces. So when Deutsche Grammophon issued LPs by the Leningrad Philharmonic, under its great conductor Evgeny Mravinsky or his associate Kurt Sanderling these were revelatory. Sanderling undertook Tchaikovsky's Symphony No 4 and the Rachmaninov – he was, of course German, and had gone to Soviet Russia in 1936 to avoid Nazi persecution. Although cut mostly in the finale, his reading (which was produced in Berlin) set an exciting benchmark – not met in his Philharmonia/Teldec remake.

Yuri Temirkanov, who worked alongside Mravinsky from 1967, became the orchestra's music director in 1988, and he recorded the Symphony for RCA in 1995 [090266-61281-2]. This time, too, the orchestra (now the St Petersburg Philharmonic) was visiting abroad: the CD was produced at Henry Wood Hall, London, and – unmistakably! – engineered by Tony Faulkner. This is a searching, profoundly satisfying account.

Guest conductor of the Royal Philharmonic, Temirkanov also made a complete version for EMI in 1978 [ASD3606] which earned a deserved audiophile following. This reappeared as a Mobile Fidelity half-speed mastered LP [MFSL 1-521].

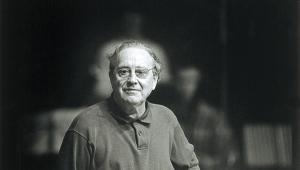

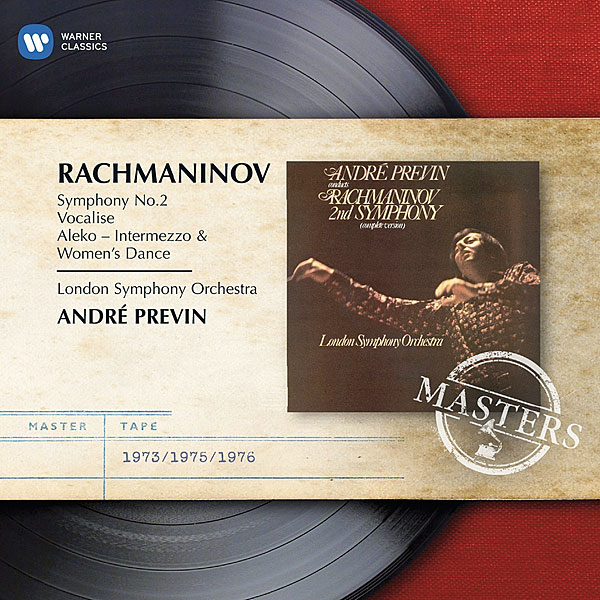

The start of the work very slowly emerges from a gloomy background. As with Mahler's First you might wonder when the 'symphony' begins – no cuckoos here though! But it's the two-halves Adagio that is the Romantic heart of the music, with that wonderful clarinet theme, echoed later by solo violin. As played by John Georgiadis in André Previn's second LSO recording, it's a heart-stopping moment – unmatched in any other version. This also has the advantage of Jack Brymer, clarinettist in (iii).

This Rachmaninov symphony was the centrepiece of their Russia and Far Eastern tour of 1971. By this time Previn had decided to observe every note of the score (although his earlier cut RCA recording, SB6685, is extremely listenable – indeed you might prefer its fresh sound quality, secured by Kenneth Wilkinson, to the EMI successor) and for many this is the CD to have. Writing about it in Classical Companion [HFN Aug '15] I noted the deletion of Testament's 180g vinyl transfer and it's a shame that Warner Classics has yet to take up this challenge, although it too has started vinyl reissues.

For anyone who thinks the later Previn is 'too Hollywood' then there are two fine Ashkenazy recordings with European orchestras: live with the Philharmona and – with generally shorter timings and less exuberance in (iv) – the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, part of a series with all three symphonies, The Bells, Symphonic Dances, etc [Decca 455 7982].

Dark Horse

In the late 1930s and early '40s the composer was recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra for RCA, and working with Stokowski and then Eugene Ormandy, who recorded Symphony No 2 there in 1951 [Naxos 9.80342; download only], 1959 and, less persuasively in a complete version from 1973. There's also a 1979 live performance on a EuroArts DVD [2072258] – this has been uploaded to YouTube.

It's all too easy to pigeon-hole Sir Neville Marriner as a 'Classical' conductor, but in later music he could surprise: Shostakovich with John Ogdon, Strauss's Metamorphosen, Elgar's In The South, for example. And his Rachmaninov Second with the Stuttgart Radio Orchestra shows him as a 'dark horse' candidate. I came across it online, sampling from a recent big Stuttgart Radio box set on Capricco, although this work you can buy separately. The orchestra isn't as opulent as, say, Maazel's Berlin Philharmonic, Weller's LPO or Temirkanov's St Petersburg orchestra, but Sir Neville perfectly conveys both the structure and intent of the piece.