Seiji Ozawa: Conductor

Atough game of rugby football put an end to the hopes that a young Japanese boy would become a concert pianist. Seiji Ozawa, then 15, was mad about the game but severely damaged his hand in a scrum. When his piano teacher suggested he might think of conducting instead, he had never even seen a symphony orchestra, live or on television.

His parents were living in Japanese-occupied Manchuria when Seiji was born, on 1st September 1935, and when he was six they came to live in a Tokyo suburb. His mother had given his older brother an accordion which sparked his interest in music and he began piano lessons at ten. There was no piano at home but you can see, in a Classic Talk TV interview, the old Yamaha upright that his brothers trundled in a handcart from a distant relative's – a two-day trek!

He went with his mother to the renowned teacher Saitō Hideo, whom she knew, and after studies won first prize at the 1959 Besançon Young Conductors Competition. There, the conductor Charles Munch was adjudicating and a star-struck Ozawa asked if he would take him on as a pupil.

'No,' said Munch but he promptly contacted Madame Koussevizky at Tanglewood in the States (Munch was then principal conductor for the Boston Symphony) and Ozawa was able to go there. She offered him a choice: working with George Szell at Cleveland or Leonard Bernstein in New York. Ozawa says he didn't know of Szell and had no idea where Cleveland was, so he became an assistant to Bernstein.

Ozawa had also won an award to study with 'Maestro von Karajan' (as he still respectfully calls him). He found him shy – self-contained, in contrast to the affable 'Lenny'.

At that time he made his concert debut with the San Francisco Orchestra in 1962. The next year he made a lauded Ravinia Festival debut with two concerts with the Chicago SO and a few months later took up the appointment of the Festival's music director. His first recording was with the CSO: Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade [Angel Records].

Boston (Long) Tea Party

With engagements in Berlin, Paris, Vienna and the States, Ozawa now looks ascance at his own neglect of languages. 'It was a joke,' he says, 'though not a joke at the time!' (He had of course quickly to switch from speaking Chinese to Japanese as a very young boy.)

But back home things had gone less well with the NHK Symphony Orchestra, where he had a six-month contract in 1962, several players refusing to play under him, finding him brash. Instead he went to the Japan Philharmonic (a Tokyo broadcasting orchestra), although this ran out of funding and was replaced by the New JP with Ozawa working alongside Naozumi Yamamoto, who had first tutored him under Hideo's supervision.

Much later (in Sep '84) Ozawa founded the Saito Kinen Orchestra, named after his mentor and at first comprising former students but then engaging international players. Only one other conductor, Daniel Harding, has recorded with them – Strauss's Alpine Symphony, but that's surpassed by Ozawa himself, but with the VPO [Philips 483 0113].

After four years with the Toronto SO and seven in San Francisco, Ozawa moved to Boston in 1973, staying there for an even longer time than the great Serge Koussevitzky, until giving as his 2002 farewell concert Mahler's Symphony No 9. That year he was invited to be the principal conductor at the Vienna State Opera.

In December1998 the critic Greg Sandow wrote a withering overview of Ozawa's Boston years for the Wall Street Journal, which you can find on line along with response and counter-response – ironically he concluded with a post-script hurrah that James Levine would take over!

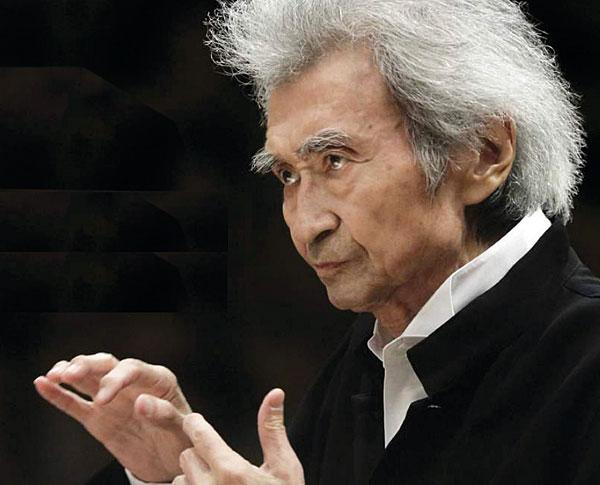

'He still dances on the podium with his trademark pixie charm… [but] I have no idea what Mr Ozawa thinks of the music, or what he is trying to express,' he wrote. Incidentally, Ozawa mostly conducts with his hands but a 1991 YouTube Tchaikovsky Serenade with his Saito Kinen strings shows him using a baton with vigour.

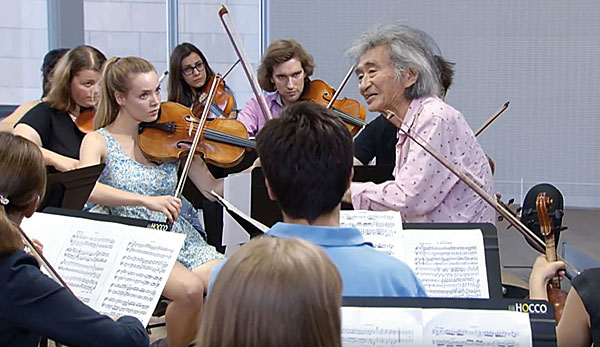

More seriously for Ozawa, he was diagnosed as having early stage oesophageal cancer in 2010 He's recovered but works less than before, here and there sharing concerts. With money from Kyoto's ROHM electronics company Ozawa has been able to work with Asian music students where, rather than choosing the symphonic repertory, he has coached them in opera – requiring shared attention to conductor and singers, and asking them to be conscious of the emotional current of the drama.

With the Boston SO he wanted to move away from their acclaimed French style (under Munch and, earlier, Pierre Monteux) and develop a darker, heavier sound. Reportedly, the leader Joseph Silverstein felt this led to muddiness.

I mentioned their early '80s Ravel orchestral series for DG in my Investigation piece [HFN May '20]. Eloquence now has these as a three-volume set, while Mother Goose and three short pieces are remastered by Pentatone [PTC5186204] from the multi-channel tapings. L'enfant et les Sortilèges marked his return to conducting after surgery [see Essential Recordings boxout, below].

Bartók On Repeat

It's the colourful scores and 20th-century music where Ozawa is heard at his best, rather than in the heavy-weight symphonic repertoire, even though his considerable discography (EMI/Warner, Philips, DG, RCA, Sony and Decca!) spans from Bach's St Matthew Passion to works by fellow-countryman Toru Takemitsu.

Karajan may have been his role-model but in the music of Bartók it's Ozawa who is generally his superior. In Chicago he made the first of his three recordings of Concerto for Orchestra, and in Boston the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (later redone in Berlin) but the 2004 Saito Kinen versions supersede those, not least because they are live [Decca 478 2472 download – see also Essential Recordings].

I remember with affection the Boston LP versions of Brahms's Symphony No 1 and Tchaikovsky's No 5. These were passed over in favour of later alternatives in the CD boxes but you can still download them. His earlier Mahler 1 too, with the 'Blumine' movt DG added later.

Surprisingly, the conversation book with Haruki Murakami [Absolutely On Music; Amazon.co.uk] suggests Ozawa felt hardly any need to delve into Mahler's personal background when studying the nine Symphonies for performance.