Johann Strauss II: Die Fledermaus

Johann Strauss's third operetta was an instant hit when it opened at the Theater an der Wien in April 1874. Austria had suffered a stock-market crash the previous year and audiences were in the mood to rinse away their troubles with buckets of sekt and a slice of escapist nostalgia. Strauss set to work and sketched the whole operetta in six weeks, boiling down a typical, if confused-looking, medley of German farce, French vaudeville (the original story by Meilhac and Halévy) and Viennese adaptation.

The advantage of these several sources was its ready supply of different entertainments within the same piece. Die Fledermaus satisfies the advice to 'make 'em laugh, make 'em cry' and throws in the circus (or, at least, a lot of dancing or cabaret).

Popular Appeal

The plot suggests the authorities are inefficient, deaf, drunk and/or open to corruption. It fulfilled at the time an audience-pleasing fantasy that a chambermaid could convincingly impersonate her employer and achieve a dream career onstage as a result. It set out hints, but never the reality, of adultery at both a classy dinner-dance and on the sofa of Eisenstein's house. The stage direction placing this house 'in a little town outside Vienna' is a double delight. No-one in the capital is accused of louche behaviour, while various in the potential audience could flatter themselves that they were being specifically identified.

The composer also entwined three styles of dance music in Die Fledermaus: the popular, the balletic and the ballroom. The mixture of song, speech and dance in a 'popular' plot – one where the audience could imagine themselves in the story – anticipated the birth of the American and French musical and over the years has proved uniquely attractive to both amateur performers and grand opera houses.

Nevertheless, the popular appeal of Die Fledermaus has not readily transferred to record (or film, for that matter, despite the efforts of directors Ernst Lubitsch and Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger, among others). If you're looking for a true-Viennese stereo Fledermaus on CD, a 'library choice' with classy conducting and stylish singing together with top-notch engineering – well, I have bad news for you.

There isn't even a CD issue of the first almost-complete recording, made in 1907 by the G&T company, sung and conducted by Bruno Seidler-Winkler with tremendous flair (head to YouTube for a surprisingly clean transfer of the 78s). All the versions listed in the Essential Recordings [opposite] enter fully into the spirit of the piece, but they are either mono, or on film, or they come with a 'buyer-beware' caveat.

Guests Of Honour

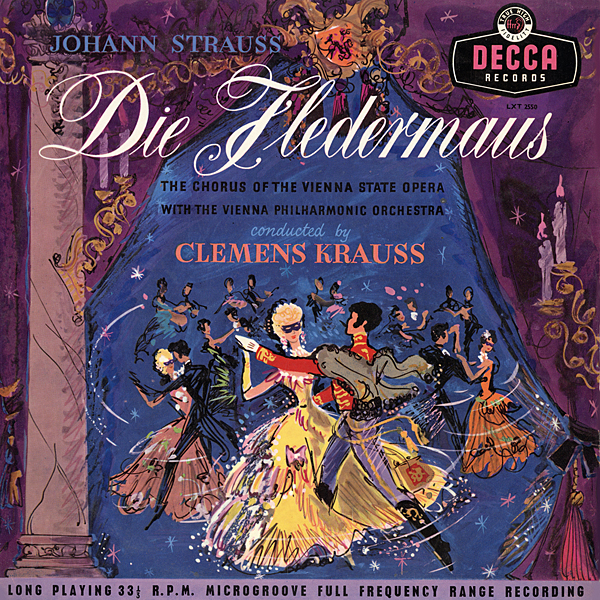

Decca had originally engaged Josef Krips to record Die Fledermaus for the new LP format in 1950. When he phoned in sick, Clemens Krauss was persuaded to return from his holidays, and the result is a gramophone classic. I can do no better than echo Carlos Kleiber's praise, writing to his friend Charles Barber: 'Krauss and his crew are by turns committed and distanced, never pasteurised or bent on proving anything. It's dry like very fine French champagne, which, as we know, doesn't "taste" as "good" as cheaper imitations. Maybe it's a dialect? I, for one, can't bring it off'.

Carlos, of course, was flattering to deceive. He knew well enough that no one else since Krauss had (or still has) mastered the insouciant flick of the waltz rhythms, the sharp point of the upstairs-downstairs satire, the effortlessly casual style of the ensembles or the homesick abandon of the mock-Hungarian czardas sung by Rosalinde in Act 2.

Kleiber's 1975 studio set is no less ebullient and fantastically detailed than his predecessor's. Both of them leave out the second-act ballet, and the Krauss recording omits all the dialogue, so that the listener must fill in the plot for themselves if the set isn't to feel like a bag of highlights. The unavoidable flaw of Kleiber on DG, meanwhile, is the casting of Ivan Rebroff, who sings the trouser-role of Prince Orlofsky in a Hinge-and-Bracket head voice. Kleiber himself apparently could barely complete a take without collapsing into giggles; for most of us, it's funny once.

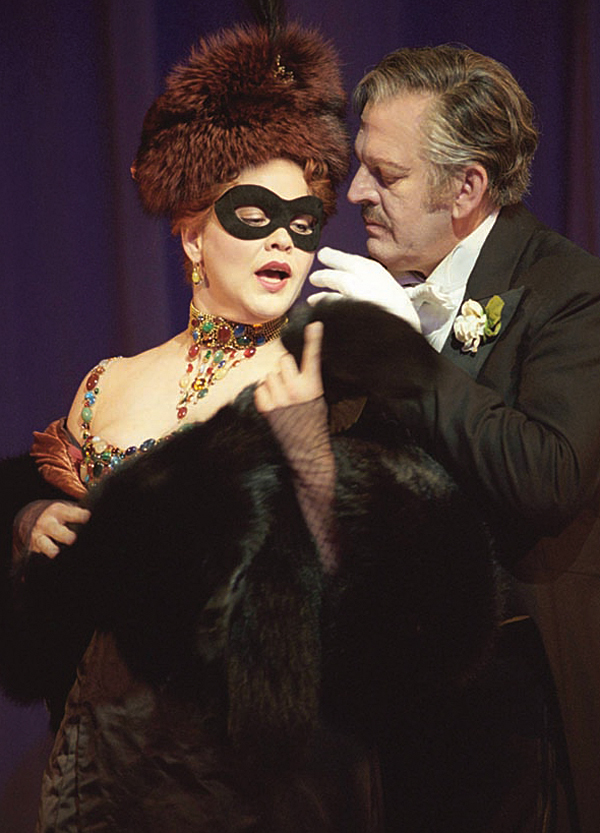

For Kleiber plus a uniformly fine cast and the sense of event which every Fledermaus should have, turn to DG's film of the 1987 Bavarian State Opera production by Otto Schenk. As Orlofsky, Brigitte Fassbaender almost steals the show. She reprised the part in 1990 for Philips; there's nothing wrong with the rapport between Previn and the VPO, but to my ears Kiri Te Kanawa as Rosalinde and Edita Gruberová as Adele sound too much like versions of their former selves and not enough like their roles.

The third K to lavish a serious maestro's care over the piece was Herbert von Karajan. His stylishly watertight 1955 recording, cast and co-masterminded by Walter Legge, takes the then-unusual alternative casting of Orlofsky as a baritone (Rudolf Christ, full of lazy hauteur), but follows Strauss's own wishes for the casting of a proper tenor (Nicolai Gedda) as Eisenstein rather than the more usual baritone. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf's Rosalinde will always divide listeners: immaculate, but hardly infused with feeling.

From just five years later, Karajan's second recording lays on the Viennoiserie much thicker: less a fault of the musicians than Decca's studio-spectacular engineering, with or without the album-length 'Gala' of vocal celebrities at the second-act ball. The more interesting sequel is Legge's, as a stereo remake for HMV/EMI, with Otto Ackermann steering the Philharmonia. The dialogue alone puts most other versions to shame for its wit and clarity. Alas, there's no up-to-date CD release.

Late Arrivals

As for the rest: once on Denon, Erich Binder's version is a fun souvenir for anyone who has seen the piece at its modern home of the Vienna Volksoper, smothered in stage and audience 'business'. Dame Joan Sutherland's New Year farewell to the Royal Opera House (Arthaus) falls into the same, repeatedly unrepeatable category. Whatever Nikolaus Harnoncourt was trying to prove (Warner Classics), he never brought it off the page, despite the opulent Concertgebouw playing.

Led by the Croatian Oskar Danon, RCA's 1964 set from Vienna is worth hearing whether complete in German (headlined by Adele Leigh's Rosalinde) or as highlights sung in modern English (Richard Lewis and Anna Moffo beautifully matched as husband and wife). Further studio-made highlights and variably recorded live recordings abound – but for a party worth returning to, stick with Kleiber and Krauss.

Essential Recordings

VPO/Krauss

Eloquence Decca 4827379/4841704 (2/16CDs)

No shortage of greasepaint or depth of field to the latest remastering of Decca's mono-era engineering at its finest.

VPO/Böhm

DG 0734371 (DVD), 4756216 (2CDs)

A 1971 Unitel film with a soundtrack Decca issued separately, featuring a cameo from director Otto Schenk as the jailer Frosch.

Bavarian St Op/Kleiber

DG 0734015 (DVD)

An international but Munich house cast, all coached by Kleiber to the last upbeat, led by Eberhard Wächter's Eisenstein.

Glyndebourne/Jurowski

Opus Arte OA0890D (DVD), OABD7004D (BD)

A rare modern success, updated to the era of Freud and flappers. The fizz never goes flat but we're aware the party will be over soon.

NDRPO/Foster

Pentatone PTC5186635 (2CDs)

First-class modern engineering in a live context, and a decent cast starring Elisabeth Kulman's aristocratic Orlofsky.

WDRSO/Haider

Capriccio C5167 (2CDs)

Another sound German radio production (this time in the studio) led by a dab hand at operetta, with a youthful-sounding cast.