Jascha Heifetz (Violinist)

For the violinist Itzhak Perlman, and others of his generation, the subject of this month's Classical Companion was a deity – 'I can't believe it. I'm talking to God – to Heifetz' he said of first meeting him when he was 14. But as Jascha Heifetz died in 1987, perhaps he's just a name on a CD cover to today's aspiring young violinists.

Jascha Heifetz was born in Lithuania in February 1901 and even when he was two his father – ever after a stern taskmaster – gave him a scaled-down fiddle and tutored him. Aged only five he was beginning lessons with Leopold Auer (the original dedicatee of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto), and in 1910 enrolled at the St Petersburg conservatory to study. Asked about his best pupils, long after he had emigrated to the States in 1918, Auer said that Jascha Heifetz was not one of his but 'a student of God'. In late 1917 Heifetz's family too had left post-Revolutionary Russia (thereafter seen by the Soviets as 'traitors') for San Francisco.

Heifetz's Carnegie Hall debut was in Oct '17 and judged a sensation. As a teenager he'd already played with the Berlin Philharmonic and after a matinee recital attended by Fritz Kreisler the Viennese master suggested 'Now we may as well break our fiddles across our knees'.

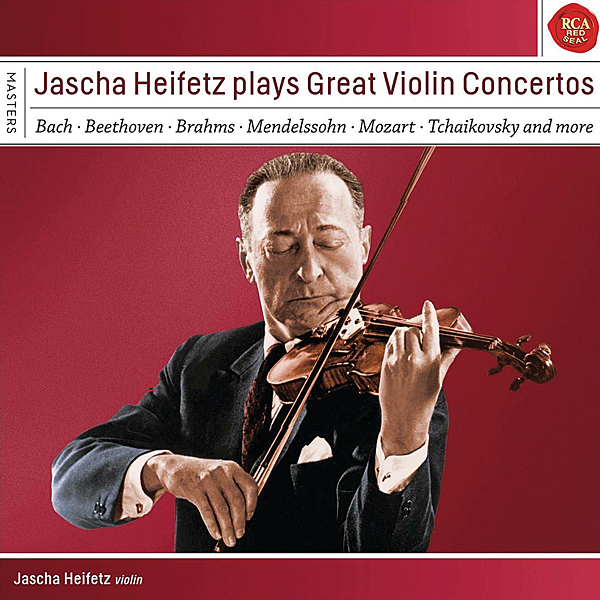

As a teenager he'd also made 78s in Russia but soon after his American concert debut he began to record for RCA Victor – remaining loyal to the company for the rest of his career, although during the Depression he came to London and to HMV. Postwar he made some light music discs for American Decca, including working with Bing Crosby, and playing his own transcription of 'White Christmas'.

He certainly embraced popular American culture (he became a US citizen in 1925), appearing in films and on television with Jack Benny, et al. He had a major role in They Shall Have Music (1939) where he's persuaded to help some impoverished schoolkids, and can be seen playing part of the Tchaikovsky Concerto, Fritz Reiner conducting, in Carnegie Hall (1947). Heifetz is but one of a string of classical musicians taking part. At the time of writing the whole film is on YouTube: skip to 1hr 40m 55s for the Tchaikovsky.

Polar Opposites

A common criticism was that Heifetz's playing was 'cold', and one cartoonist drew him playing out on an ice floe, with bemused polar bears watching. In a UK publication from 1925 a rather crude caricature was captioned 'Merry Xmas. May it be as cold as my imperturbable perfection. Yours Jascha Heifetz'. The New Grove Dictionary observed that he showed a 'chiselled, unsmiling face, even when acknowledging an ovation'.

'Cold?' says Perlman: 'he was hot!'. And, says violinist Ivry Gitlis, 'people should close their eyes, for God's sake, and just listen to the sound'. In fact, Heitetz had disciplined himself to play on stage without adding a physical 'performance' which he thought did a disservice to the music.

However, former HFN contributor Julian Haylock, in a June 2009 piece for The Strad suggested that his 'supreme concentration and focus meant that he rarely sounded truly relaxed in his music-making'. (Not with the clips I've been looking at, Julian!) And in Dario Sario's 2015 book The Performance Style Of Jascha Heifetz [Routledge; ISBN 9781315554778] the many documentary videos to be found online are analysed in depth, at one point a lack of contact while playing with his regular accompanist, Brooks Smith, being noted.

In fact their RCA LPs of Beethoven sonatas invariably not only showed the cover credits in contrasting type sizes but relegated the pianist to a distant stage balance!

Working With Walton

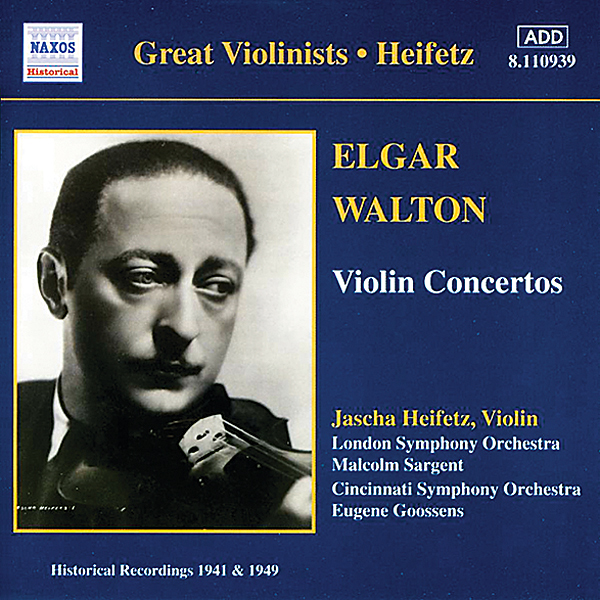

The most important of the works commissioned by Heifetz was the Walton Violin Concerto. The two were introduced by the musician/broadcaster Spike Hughes in 1936, in a London hotel. But it was a further two years before the score was finished and the concerto premiered in Cleveland with Artur Rodzinsky conducting, on the 7th of December 1939. Walton's plans to conduct it himself were thwarted by the outbreak of war.

After he had made a few revisions in 1943 (the percussion parts became less exotic) Walton and Heifetz made a new recording in London to replace the 1942 78s with the Cincinnati Orchestra under Eugene Goossens [Naxos 8.110939]. The coupling on that CD is a perhaps unexpectedly fine account of the Elgar Violin Concerto, Sir Malcolm Sargent conducting the LSO.

The revised version of the Walton was done at Abbey Road in June 1950 with the Philharmonia Orchestra and it's also on Naxos in transfers by Mark-Obert Thorn [8.111367]. Walton was wont to comment on interpretations of his music – there seems to be nothing on the Heifetz set, but when he made an EMI version with Menuhin [1970: now Warner 2564633939] he thanked the violinist 'for having brought to life a dream which I thought would never come true'.

The concerto recording I most treasure is Heifetz's third version of the Sibelius. Apparently he crossed swords with Stokowski when making a Dec 1934 recording in Philadelphia and asked for the resulting masters to be destroyed. They weren't, however, and in 2015 Guild issued the set on CD [GHCD2428]. His version with acclaimed Sibelian Sir Thomas Beecham and the London Philharmonic was made at the end of the following year and is on Naxos. For my taste, Heifetz doesn't allow the finale to breathe, although for many critics this is the definitive recording. (Buy the CD anyway for the coupled Tchaikovsky.)

My choice would be the RCA 'Living Stereo' LP made in Chicago in June 1963, not with Fritz Reiner but his assistant Walter Hendl. It was reissued as a 200g Acoustic Sounds LP [AAPC 435], and as one of RCA's short-lived series of SACDs.

To hear Jascha Heifetz at his dazzling best, try [YouTube] Hora Staccato; Saint Saens's Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (with Alfred Waxman); Wieniawski's Scherzo Tarantelle (an interesting piece of film where he auditions test pressings and is then seen playing).

In 1972 he withdrew from the concert platform after an unsuccessful operation on his right shoulder. He continued teaching – one of his best pupils, Erick Friedman, had joined him in the May '61 recording the Bach Double Concerto [in the RCA set seen above] where previously – Hollywood 1946 – he'd played both solo parts! It was in his repertory since the age of 11. Bach was his greatest love.