Handel: Theodora

It is, apparently, impossible to write about Handel's penultimate oratorio without quoting the composer's own gloomy view of its failure at the box office when it was first performed at the Covent Garden Theatre, London, in March 1750. 'The Jews will not come to it because it is a Christian story; and the Ladies will not come because it is a virtuous one.'

So there you are. As Handel hinted, Theodora occupies a unique place in his output, which may be why he was so fond of it. It is his only narrative oratorio with a Christian subject, as distinct from the Old Testament stories of Belshazzar or Judas Maccabaeus, or the anthem-like assemblage of Messiah. His audience wanted trumpeting hallelujahs, 'Jehovah with thunder arm'd'. He gave them Christian chastity, love and self-sacrifice.

Late Style

In brief: Theodora, who refuses to worship Jupiter and Caesar, is condemned by Valens, the Governor of Antioch, to become a temple prostitute. She is loved by Didymus, a Roman soldier who has secretly converted to Christianity and is shielded out of compassion by his immediate superior, Septimus. Didymus exchanges clothes with Theodora so that she can escape, but both are condemned to death after their final refusal to offer sacrifice to Jupiter and the Emperor.

Thomas Morell's libretto may not amount to much, but Handel painted its blank canvas with layer on layer of deep harmonic colours and a Rembrandt-like eye and ear for pathos. Theodora is an object example of 'late style' from a composer bent upon introspection after a lifetime of satisfying public taste. Hence its failure, closing after three performances. Posterity, however, has belatedly come to share the composer's own judgment of Theodora as his masterpiece.

Why should Theodora's fortunes have turned around so dramatically? Firstly, there was the early-music movement in the second half of the last century. This recovered something resembling an 'original' performing style for the piece, along with the kinds of instruments and voices for which it was written. This made a long oratorio like Theodora performable without drastic surgery.

Secondly, and more simply, changing tastes. As part of that revival, Theodora was recorded in the 1960s, and again in 1991 by that inveterate pioneer Nikolaus Harnoncourt – both significantly cut, both keeping the unique pathos of the piece at arm's length. The turning point came in 1996 with a full staging at Glyndebourne, directed by Peter Sellars and conducted by William Christie.

Radical Restagings

Sellars had made his mark in music theatre with radical stagings of Mozart and John Adams, in the style of a new realism. Noting the relative absence of dramatic tension from Theodora – its heroine's fate is sealed from the outset – he transferred the setting to a modern Death Row. The spare, hypnotic nature of stage movement also belonged to the American culture of music theatre that produced Philip Glass's Einstein On The Beach.

If you can find the Glyndebourne own-label CD production, or the American-import film, lucky you. It became a landmark in modern Handel performances above all for the singing of Lorraine Hunt Lieberson in the role of Irene, Theodora's sister. Curiously, Hunt Lieberson had by then recorded the title role in a stylish, but unevenly cast, US production led by Nicholas McGegan (still available on Harmonia Mundi).

'I don't know any work that so transcends its libretto', she remarked. 'The outward aspects of language are almost done away with and Handel takes you right to the spirit and emotions of the characters.' With her early death from cancer in July 2006, Hunt Lieberson became immortalised not simply as Theodora but Theodora in the wider imagination.

The life of the piece itself, however, has flourished since then, and found a natural home on the world's opera stages rather than concert platforms. Handel himself had given up writing opera in 1741 with Deidamia, but his oratorios were still performed in the same spaces, and to the same audiences, with many of the same singers. For example, the role of Didymus was created at the premiere by the castrato singer Gaetano Guadagni.

Drama Of The Mind's Eye

Many years ago I was running a CD store in Cambridge when a noted Handel authority walked through the door and requested Theodora on CD. I pointed her to the opera section, whereupon she lectured me for my ignorance. I wonder how she would take to Christof Loy's 'Making Of' staging for Salzburg. This begins in rehearsal conditions, makes the cross-dressing of Theodora and Didymus central with a devastating simplicity, and focuses on the inner life of the music with a hieratic movement shared by Sellars in his staging of the Bach Passions.

More radical still was Katie Mitchell's recent staging for The Royal Opera, in which Theodora's sentence to a form of sexual slavery likewise finds an entirely direct modern equivalence, though the ending has nothing to do with Morell, or Handel. Irene was sung by Joyce DiDonato, who has inherited Hunt Lieberson's mantle as an embodiment of the work's tragic pathos, most of all in the rapturous stillness of 'As with rosy steps'.

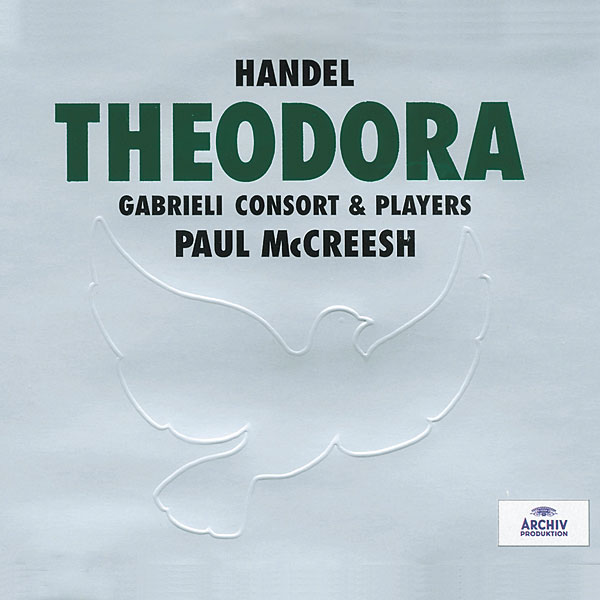

There is still a place for Theodora as a drama of the mind's eye rather than a godless meditation on death/abuse/sacrifice, and as an English oratorio not a million miles from Handel's previous achievements in the genre. In this regard, Paul McCreesh's CD recording for DG/Archiv has much to offer.

Arty Accents

Previous recordings of Messiah and (especially) Solomon established a 'Gabrieli' style in Handel, blending colour, grandeur and sobriety.The restraint and dignity of Susan Bickley's Irene makes a refreshing change. Robin Blaze's Didymus majors on nobility of phrase rather than self-pitying heroism.

The many choruses of Theodora, too, make quite a different effect when sung not by the individualistic timbres of opera choruses but by an early-music choir such as the Gabrieli Singers. They make sense of the big contrapuntal choruses without recourse to arty accents and attacks.

McCreesh's sure-handed direction establishes a weighty pulse for climactic moments, most of all 'He saw the lovely youth', which ends Act 2. This chorus tells the story of the son of the widow of Nain whom God called back to life. In it we may hear the aging Handel's profession of faith, a profession in oblique relation to the stated articles of Christianity. He much preferred it to 'Hallelujah'. Perhaps you will too.

Essential Recordings

Gabrieli Consort/McCreesh (2000)

DG Archiv (3CDs)

English singers and direction adjacent to the 'oratorio tradition'. Theodora as Handel might have heard it, or wanted to hear it.

Il Pomo d'Oro/Emelyanychev (2021)

Erato/Warner Classics 5419717791 (3CDs)

No shortage of star wattage or studio polish: no longeurs, either, despite directorial moments of self-indulgence.

Orchestra of the Antipodes/Helyard (2016)

Pinchgut Opera PG009 (3CDs)

A live staging from Sydney, overflowing with greasepaint to evoke a staging of the mind on CD, pacily directed and vividly sung.

Freiburger Barockorchester/Bolton (2000)

C major 705804 (Blu-ray); 705708 (DVD)

The inner turmoil of the characters exposed with rare insight by Christof Loy in a spare and well-cast Salzburg staging.

Royal Opera House/Bicket (1996)

Opus Arte OABD7313D; OA1368D (Blu-ray; DVD)

DiDonato almost steals the show in Katie Mitchell's politically 'hot', bombs-and-brothels staging for The Royal Opera.

OAE/Christie (1996)

Kultur BD2099 (Blu-ray)

Peter Sellars's staging for Glyndebourne that revived Theodora as a parable for our time and immortalised Hunt as Irene.