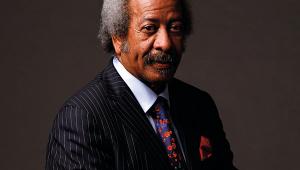

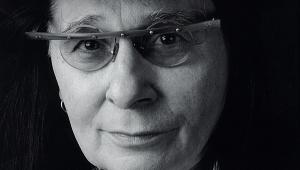

Gus Dudgeon

In the Spring of 1968, David Bowie, a pop star with a failing career, sat through Stanley Kubrick's trippy masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey at least three times at the Casino Cinerama in Old Compton Street. 'It was the sense of isolation I related to,' he explained later. 'I found the whole thing amazing. I was out of my gourd, very stoned when I went to see it – several times – and it was a revelation to me. It got the song flowing.'

The song in question was 'Space Oddity', a piece that was being cooked up to coincide with the USA's soon-scheduled moon landing. Bowie had recorded a demo of the song in late 1968 for a short promotional film that was canned called Love You Till Tuesday. That version wasn't much cop – Bowie mimicked the spaceship sounds himself – but it brokered him a deal with Mercury Records who signed him for an album to include a fuller version of 'Space Oddity'.

Cheap Shot

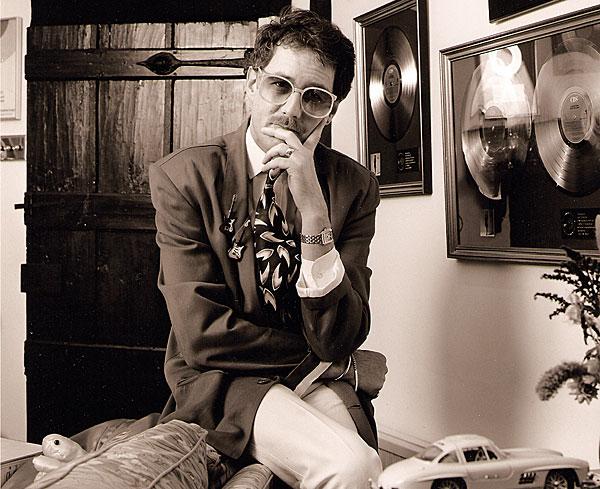

Bowie assumed that he'd be working with his friend Tony Visconti but the producer hated the song, calling it 'a cheap shot – a gimmick to cash in on the moonshot'. Enter Angus Boyd Dudgeon, known as Gus. At the very point that Bowie needed a wiz to craft 'Space Oddity', Dudgeon was assisting Visconti and others in the capacity of studio engineer and fledgling producer and the task was duly tossed in his direction.

Dudgeon had started out as tea boy at Olympic Studios on Baker Street in London in the early '60s, later joining Decca Studios in West Hampstead as a staff engineer. While at Decca in the summer of 1964, he engineered the debut single by a band of young lads from St Albans who'd won a contract via a Beat Group Competition run by the Evening News newspaper.

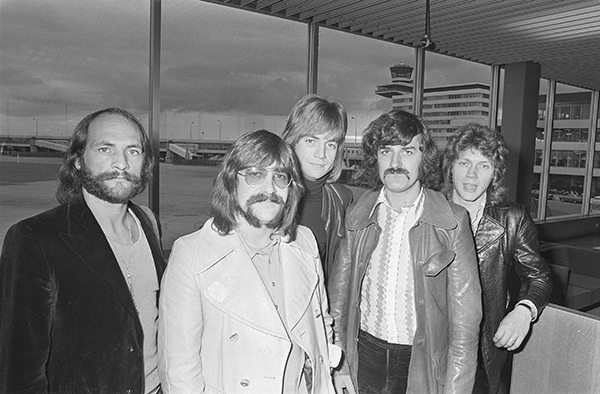

That band was The Zombies and the track, beautifully balanced between jazz and pop, delicately delivered by songwriter Rod Argent and blissfully sung by Colin Blunstone, was 'She's Not There', an immediate Top 20 hit.

He'd also worked as an engineer on John Mayall's Bluesbreakers album featuring Eric Clapton which launched the whole UK blues boom in 1966, and with The Moody Blues and Marianne Faithfull among many others. It was the session with The Moody Blues that launched him into producing in his own right.

Fight Song

'I was doing a four-track Moody Blues session that Denny Cordell (the producer of Procol Harum, The Move, Joe Cocker, etc) was producing, and I was really pleased with the sound we'd achieved,' Dudgeon explained. 'It was difficult in those days to get a great sound on every single track. If you put a rhythm track together, you might have as many as five different people on one track. When you got a great sound and a really good balance, it was really not worth changing – I would fight for it. On this occasion, the Moodys got to the session, and they wanted me to change the EQ and add echo all over the place. I was getting more and more p****d off. And then Denny came in about an hour into the session and said, "Play me what you've got".'

Pretty Stupid

Before I played it to him, I said, 'Listen Denny, before you hear this, I've got to tell you that, since you've heard it last week, the guys had me stick all kinds of s**t all over it'.

'And he went, "Well that's probably what they want. Let's have a listen to it". So I played it, and he said, "Well, it sounds all right to me". And I said, "Well Denny, can I just play it to you without any of the effects on it?". He said, "No". I said, "Why not?". He said, "That's what the boys want". I went, "I think that's pretty stupid. A week ago when we did the session, you loved it". And he said, "Well I think it sounds fine now".

'So he got p****d off and rang the head office. They called me back and said, "Listen, you can't talk to Denny like that. We've just given him his own label. He's an important producer". I said, "Yeah, but surely my opinion isn't valueless". They said, "Well, you've got to go back into the control room and apologise to Denny". So I put the phone down with my tail between my legs and went back into the control room, and Denny said, "Gus, do me a favour. Just let me hear what it is you're talking about". So I took off all the EQ and the effects and played it to him flat. And he said, "You're absolutely right. That's ten times better. Run it off the way you want to do it". And I went, "Oh, OK".

'As he was leaving the control room, after the end of the mix, he said, "I reckon you should get into production. I think you'd be good at it". I was amazed.