Carlos Kleiber: Conductor

Iam very slow on the uptake. But now I know what's wrong: the quavers are too low on nicotine. They need a little bit more tar – they have to be a bit more venomous…' And: 'the side-drum has to edge its way in. It has to be very conspiratorial, a schizophrenic back and forth between sentimental and rumbustious'. Not the sort of rehearsal instructions orchestral players would be used to – but then, Carlos Kleiber was different.

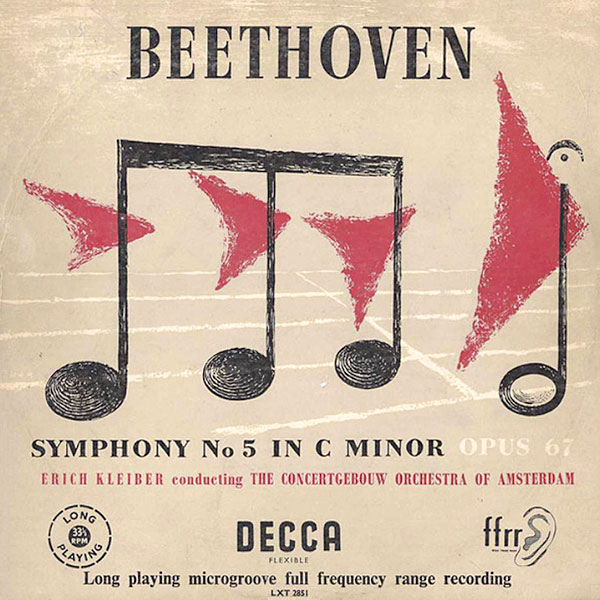

When he first told his father, the great Austrian conductor Erich Kleiber, that he too wanted to conduct he was bluntly told 'One Kleiber is enough!', and was packed off to study chemistry in Zurich. But as his sister remarked, in the EuroArts documentary Traces To Nowhere [to be found on YouTube], Carlos at one time worked under an alias. And later, Erich Kleiber did acknowledge his son's huge talent.

Born Karl Ludwig, in 1930, his name was changed when the family moved from Germany to Buenos Aires in 1935. As a 'modernist' – conducting Janáček, Krenek, Milhaud, et al, he'd premiered Berg's Wozzeck: a work which the Nazis deemed 'degenerate' – Erich Kleiber had felt impelled to resign his post at the Berlin State Opera.

Wozzeck was later one of Carlos Kleiber's key successes at Stuttgart and he brought the work, and the Staatsoper to the Edinburgh Festival in 1966 (his first UK appearance). As so often, he was using his father's marked scores – it has been claimed that he only conducted works with this precedent (Henze's Ondine is one obvious exception, with 27 performances given from 1961-66).

He was 'a dictator, but very human and supportive with it,' says mezzo Brigitte Faessbender – although she remembers him sending a little note 'How could you do this to me?', after a couple of minor fluffs during a Rosenkavalier performance with him.

You can see a short clip from a Stuttgart Der Rosenkavalier online showing Kleiber's extraordinary fluidity of arm and body movements, while film of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde (see Georg Wübbult's documentary I Am Lost To The World) shows the utter intensity he conveyed in the opera house. There's also a split-screen comparison of father and son in the same Johann Strauss piece.

Kleiber would never beat time in a conventional manner, but his expressive body language was all the players needed. In the famous New Year Day concerts in the Vienna Musikverein (1989/92), and in classical pieces too, sometimes he'd drop the baton to one side and just briefly leave the players alone – once he set up a metronome in rehearsal, claiming he could do no better!

An Audi, Thank You

For his scant later appearances he asked for huge remuneration – the conductor Michael Gielen reckoned that his fees for taking Der Rosenkavalier to Japan would have set him up for life; and for one concert he requested a fully customised Audi. But as his sister Veronika said 'For him the money side was like a gauge of his importance'. He seemingly felt he never reached the same level attained by his father.

Fassbaender found him, at times 'given to outbursts of hilarity, almost like an adolescent'. His sense of play extended – in one performance of his much-loved Die Fledermaus, after the Act 2 interval – to dressing as Boris Becker, wig and all, conducting using a racquet and tennis ball.

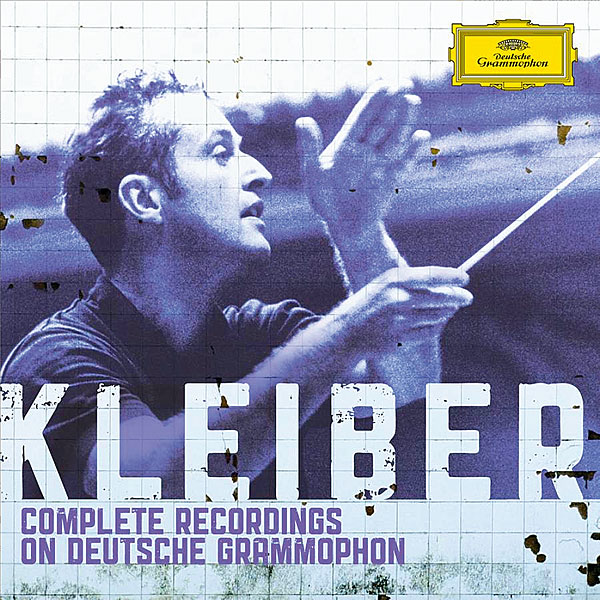

Kleiber used to recommend the old Clemens Kraus recording [Decca] while his own [DG 457 7652] proved controversial in the casting of Ivan Rebroff – a 'falsetto' Orlovsky.

Two important works (both on CDs with technical deterrents) he only conducted once were Mahler's Song Of The Earth and Beethoven's 'Pastoral' Symphony. He agreed to stand in for Josef Krips to conduct the Mahler composition with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra on June the 7th 1967. Preparing the work, he met with Otto Klemperer in Zurich to discuss Mahler's score in detail. A much-pirated tape copy was finally remastered for the VSO's own label [WS007]. It proved to be Christa Ludwig's night (Waldemar Kmennt, the tenor, was far too close-mic'd), so worth hearing for her.

But given the technical problems with the sound I'd suggest listening to the YouTube upload rather than spending money. And after the success of his live Symphony No 4 [Orfeo C100841B] the 'Pastoral' was rather disappointing – it was transferred from a Nov '83 cassette recording made by Kleiber's son [Orfeo C600031B]. These are both with the Bavarian State Opera Orch.

One recording that was much anticipated, we never had. Kleiber was to record R Strauss's Ein Heldenleben with the Vienna Philharmonic for Sony, but either walked away or refused to allow publication (YouTube has a 1993 VPO concert version). And we might never have had his Dresden Tristan und Isolde, which some sources say he declined to approve, although Gramophone says he assisted in the digital remix for CD [DG 477 5355].

He was a constant source of bewilderment and frustration. Conductor Manfred Honeck (then in the VPO): 'Time and again he first said yes, then called the next morning to say he'd changed his mind. A short note "I'm off into the blue" and that was it'.

Kleiber liked nothing more than to drive back to the Slovenia home that he had built, in Konjšica – as Karajan put it 'he only came out when his freezer was empty'. Diagnosed with untreatable prostate cancer, he died seven months after his wife Stanislava, a former ballet dancer, in July 2004. The two had met when he was conducting at Düsseldorf in the early '60s.

Open Apology

Shortly after the success of his Beethoven 7th and Schubert No 3 LPs he gave two concerts with the LSO including these symphonies, in June 1981, Milan then London. But the critics here were hostile and the Observer's Peter Heyworth wrote an open apology on their behalf. Needless to say, Kleiber never returned to the Festival Hall.

Music-lovers who regularly watched the TV transmissions from Vienna on the 1st of January will remember the shock of this elegant new figure patently enjoying the sounds he choreographed in 1989 [see 'Essential Recordings' boxout, below] and again three years later. A rehearsal clip shows how hard he worked even in the VPO's core Strauss repertory.

Violinist and former VPO Director Clemens Helsborg said 'In art there are no upward limits. Yet each generation needs at least one artist who exemplifies this. Carlos Kleiber reached to the stars for us; even when he broke down in his efforts, he still proved that they exist'. Kleiber himself said, enigmatically, 'One shouldn't leave traces in life'.